Our world is becoming dangerously polarized. As we converse with friends and colleagues on social media, we forge connections with people of like mind–those who share our beliefs and opinions. As these opinions receive increasingly more validation from fellow members of these mini-societies, we become more entrenched in the perception that our opinions are truths. It becomes increasingly more difficult to understand how anyone could have an opinion that differs from ours. In the early stages of this process, we begin to attribute motives to those who hold contrary opinions and this later manifests into a dismissal of all who disagree with us as “stupid” or “out of touch.” This issue emerged in a recent internet post titled, “Why is freedom of speech important when most people don’t have anything important, intelligent, or insightful to say?”

On Einstein’s second visit to America, a reporter challenged him with the assertion, “Mr. Edison contends that a college education is of little value.” Einstein responded, “The value of a college education is not the learning of many facts but the training of the mind to think.” In this comment, Einstein was talking about the scientific method for reaching opinion. As we study the sciences, we form hypotheses that we regard as first approximations to the truth. If observations support a particular hypothesis, it becomes tentatively accepted as true, otherwise it is rejected and an alternative hypotheses is advanced. A sequence of hypotheses, validated by observation, becomes the basis of a science, building on an edifice of successive approximations and tentatively accepted as “truth.” When an observation is made that contradicts what the scientific model predicts, the original assumptions are examined and sometimes the entire structure collapses, requiring a rethinking of the original hypotheses. This is what Einstein did when he challenged the belief that time is absolute and thereby revolutionized physics. Education, whether formal or informal, trains us to challenge constantly what we believe by asking ourselves, “What is my basis of certainty?”

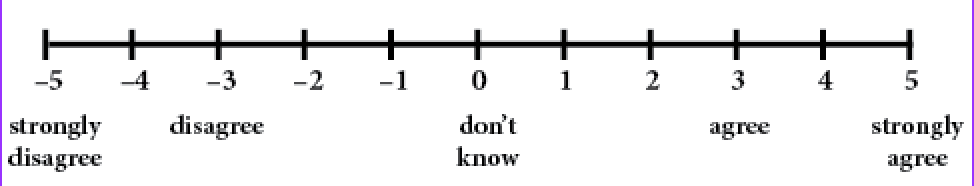

This methodology can be expanded from scientific hypotheses to all assumptions or beliefs. For example, consider a hotly-debated issue that has widespread ramifications, polarizing those on opposite sides of the political spectrum: gun control To explore your opinion on this issue, choose and record a number between –5 and 5 that describes the degree to which you support the following assertion.

It should be illegal to manufacture, sell or possess high-capacity semi-automatic rifles such as the AR-15, AK-47 or M16.

Then visit: https://academic.oup.com/epirev/article/38/1/140/2754868

There you will find a comprehensive meta-analysis of national and international research on all aspects of gun legislation and its consequences. Clicking on the icon for the PDF version of this report will enable you to obtain a viewable and printable copy with page numbers. Scan the various graphs to gain a sense of the diversity of the results. The assertion above is addressed on page 149 under the heading “Laws targeting specific firearms and ammunition.” After reading this section, visit the conclusions section of the report, beginning on page 152 and reflect on what you’ve read.

Now choose a number between –5 and 5 that describes the degree to which you agree with the statement above. Compare this with the one you recorded earlier. Did the article change your opinion about the truth of the statement? If not, why not?

If you originally chose either “strongly agree” or “strongly disagree” and did not modify your belief after reading that article, you might ask yourself, “What is my basis of certainty for my opinion on this issue?” When conversations between two people of differing beliefs begins to escalate from the cerebral to the visceral domain, nothing useful results. Differences of opinion must migrate from the world of belief to the world of research. Opinions based on what we would like to believe, rather than what is in fact true, will eventually be proven false. Though there are some so-called “undecidable propositions,” that can be neither proved nor disproved, we must always revert, where possible, to suspending our certainty until some substantial evidence supporting our opinion is available.