En route to our discussion of ChatGPT, we have been providing a very brief summary of some of the milestones in the development of artificial intelligence (AI) that have brought us to a point where many computer scientists are advising that we declare a temporary halt to further development until we can establish some “guardrails” that will prevent us from plunging over the cliff of no return. In Part I, we described the early stages of artificial intelligence in which IBM’s Deep Blue computer defeated Grandmaster Gary Kasparov in a chess tournament signalling the beginning of computer superiority in all strategic games. In Part II, we discussed the use of associative nets to train computers to understand metaphor and grasp the dimensions of meaning, thereby laying the groundwork for computers to read and “understand” natural language. In Part III, we will look at the next stage in this evolution–shape and face recognition. Most of the following is excerpted from the book Intelligence: Where we Were, Where we Are & Where we’re Going.

Shape and Face Recognition

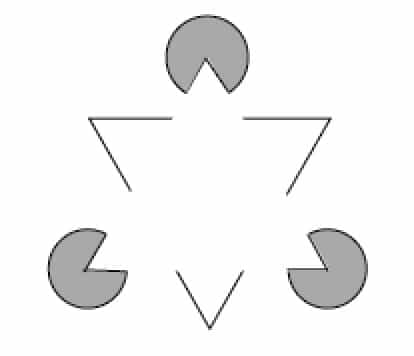

As we humans evolved, our brains developed the ability to perceive distinct shapes and surfaces embedded in various backgrounds. Shape recognition has also been observed in newborn ducks that ignore silhouettes of non-predatory birds, but panic when shown the silhouette of a hawk. The ability to infer the shape of a predator embedded against a camouflaged background is so vital to human survival that we sometimes perceive a shape where none exists. In the configuration shown in figure 24.4, we “see” a solid white triangle in the foreground obscuring another white triangle with a black border in the background. When we identify immediately a human face embedded in a mosaic of fragments, we are synthesizing into a holistic image what might appear to a computer as random pixels.

Identifying shapes and objects in a photo is something our brains do instantaneously, but a computer has to compare millions of pixels just to be able to select boundaries of regions let alone recognize an image of, say, bald Uncle George. Indeed, face recognition is one of the most important survival skills in many of the “higher animals.” Frans De Waal, author of the book, “Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?“, reports that face recognition capability has been detected in chimpanzees, crows, sheep, and even in wasps.

Our capacity to recognize faces is embedded in our DNA, but the facial images stored in our brains are acquired through our experiences. We have various images of Uncle George buried in our brain, so even if we were too young to remember him with hair, we can still recognize him in his wedding photo at the peak of his virility. Mimicking how humans acquire face recognition, researchers in AI developed character recognition software by feeding millions of variations of a letter such as A into a computer and having it extract the essential features of that character. Ray Kurzweil, developer of the first omni-font optical character recognition software explained:

“We spent years training a set of research computers to recognize printed letters from scanned documents … If you want your computer to recognize printed letters, you don’t need to spend years training it to do so, as we did–you can simply download the evolved patterns already learned by the research computers in the form of software.”

Ironically, when bots (computer programs or “robots” executing cybercrime on a website) were registering as humans, a “reverse Turing test” had to be implemented to distinguish between the bot and a human. By 1997, AI researchers had developed the CAPTCHA (acronym for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart). The fonts had to be grossly distorted so that humans registering on a website could apply their superior shape discrimination faculty to read and respond to the CAPTCHA while the bot would be “botfuddled.”

Kurzweil also developed software for speech recognition by a process in which sound was converted into wave forms that were sampled for the frequencies of highest intensity, and isolated from random noise. Explaining how he and his associates developed this software using the mathematical concept of Markov chains he noted:

“People often fail to appreciate how powerful mathematics can be–keep in mind that our ability to search much of human knowledge in a fraction of a second with search engines is based on a mathematical technique.”

Advances in voice and character recognition near the end of the 20th century and into the 21st gradually reduced the gap between human and machine intelligence as defined by the Turing test. Information from the natural and social sciences, as well as literature, the arts, and sports were stored in computer memory enabling the computer to answer questions involving associations such as those on the Miller Indices tests and on the television quiz show, Jeopardy!. In fact, in 2011, IBM’s intelligent machine, Watson, soundly defeated Jeopardy! champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. Three of the questions that Watson answered correctly are shown below.

1. Wanted for a twelve-year crime spree of eating King Hrothgar’s warriors; officer Beowulf has been assigned the case.

2. Four-letter word for the iron fitting on the hoof of a horse or a card-dealing box in a casino.

3. In act three of an 1846 Verdi opera, this Scourge of God is stabbed to death by his lover, Odabella.

The answers to those questions are respectively, Grendel, shoe, and Attila the Hun. Clearly, Watson had received extensive education in literature and the arts, though it is not clear whether Watson enjoyed the opera. Many regarded Watson’s victory as a “coming of age” in which artificial intelligence had passed the Turing test. Others echoed the skepticism of Noam Chomsky, expressed in an interview with Gavin Schmitt, “Watson understands nothing. It’s a bigger steamroller. Actually, I work in AI, and a lot of what is done impresses me, but not these devices to sell computers.”

A lot has happened in the decade since Chomsky’s comments yet, at age 94, he still retains some pessimism about computer acquisition of natural language (see YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-NMR5JXp37k) Others, however, believe that bots are on the verge of passing the Turing test. We will visit additional perspectives in Part IV.