During your early years, your brain was attempting to adapt to your environment. During your first two years of existence, the neurons in your brain were connecting at the rate of about 2 million synapses per second, so that by age 2 you had about 100 trillion synapses–about double the number you have now. In the years that followed, your brain went through a series of prunings, removing the synapses that were not used or needed and reinforcing those that came into play

By the time you reached adulthood, you had adapted to your environment and the changes in your brain began to slow. As you entered middle age, you applied your learning toward achieving your life goals. The procedures and routines you had learned served you well during that period.

As you entered the final years of middle age, you had developed a comfort in following the tried and true methods that had served you through most of your life. However, the environment continued to change, while your need to adapt may have declined. You became set in the “old ways” and began to lament the loss of comfort that accompanied the demand to adapt to a new environment.

At this point, you were faced with a dilemma. Should I resist the changes and lament the past, or should I embrace the future and begin once more to adapt to a new environment?– the dilemma that Charles Dickens presented in the character of Fezziwig in “A Christmas Carol.”

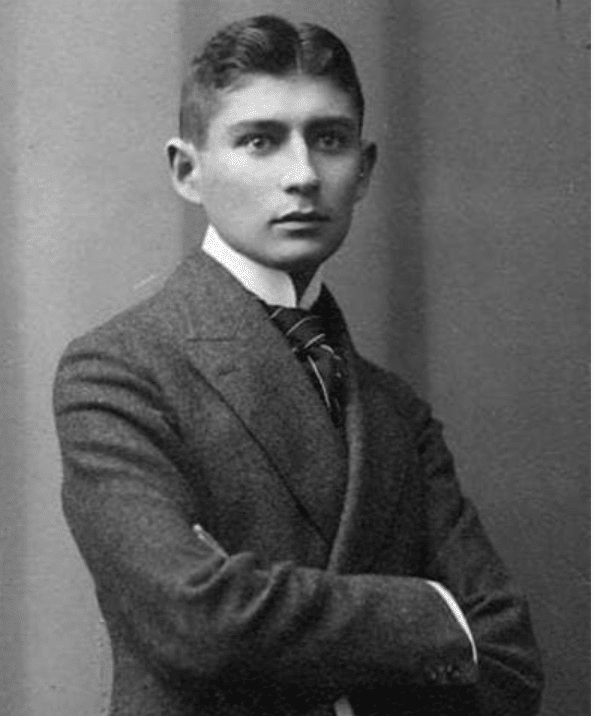

In the clip below, forwarded to me by Nadya Kelly from the Facebook blog “A Good Read”, celebrated Czech author Franz Kafka provided his answer to this dilemma.

At 40, Franz Kafka (1883-1924), who never married and had no children, was walking through a park one day in Berlin when he met a girl who was crying because she had lost her favourite doll. She and Kafka searched for the doll unsuccessfully. Kafka told her to meet him there the next day and they would come back to look for her.

The next day, when they had not yet found the doll, Kafka gave the girl a letter “written” by the doll saying “please don’t cry. I took a trip to see the world. I will write to you about my adventures.” Thus began a story which continued until the end of Kafka’s life.

During their meetings, Kafka read the letters of the doll carefully written with adventures and conversations that the girl found adorable. Finally, Kafka brought back the doll (he bought one) that had returned to Berlin. “It doesn’t look like my doll at all,” said the girl.

Kafka handed her another letter in which the doll wrote: “my travels have changed me.” The little girl hugged the new doll and brought the doll with her to her happy home.

A year later Kafka died. Many years later, the now-adult girl found a letter inside the doll. In the tiny letter signed by Kafka it was written: “Everything you love will probably be lost, but in the end, love will return in another way.”

Embrace change. It’s inevitable for growth. Together we can shift pain into wonder and love, but it is up to us to consciously and intentionally create that connection.