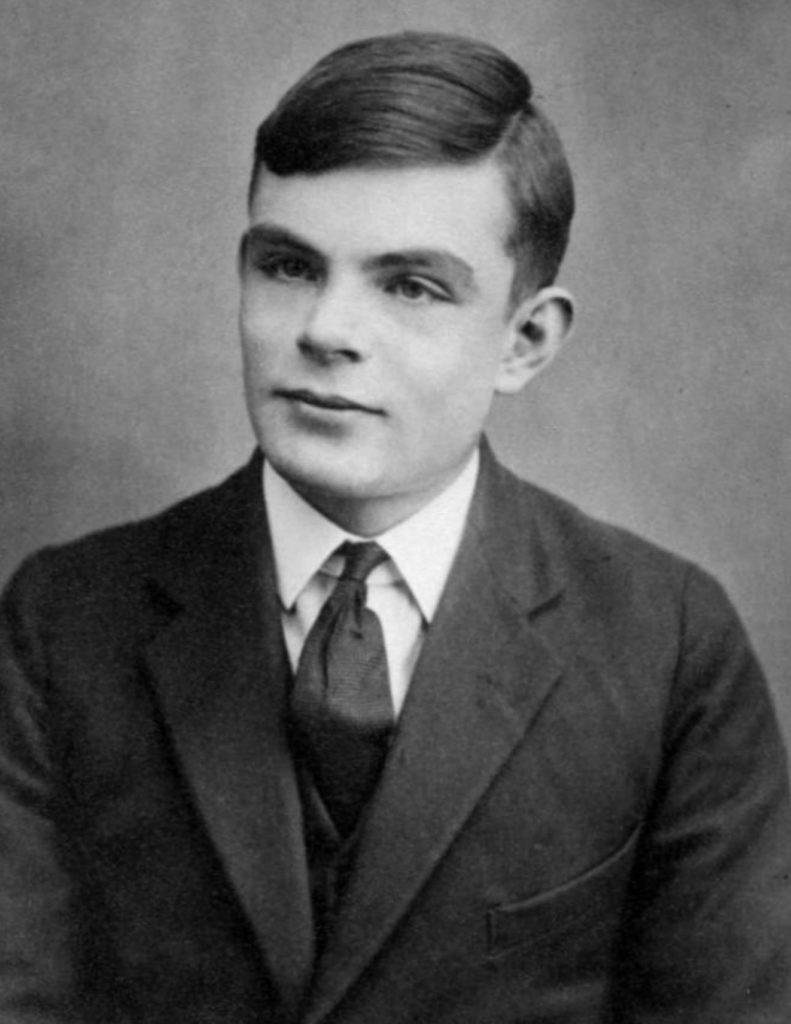

Alan Mathison Turing was born on June 23, 1912 in London, England. Between ages 6 and 9, Alan was enrolled at St Michael’s, a primary school where the headmistress recognizing his talent, noted, “[I have] had clever boys and hardworking boys, but Alan is a genius.” In 1926, Turing entered the Sherborne Boarding School where he met a fellow student Christopher Collan Morcom with whom he formed a close relationship. However, in 1930, when Morcom developed bovine tuberculosis, and died, Alan dealt with his grief by immersing himself in the study of mathematics.

In 1931, Turing enrolled at King’s College, Cambridge, where he achieved first-class honours in Mathematics. In 1935, at the age of 22, he provided an original proof of the Central Limit Theorem and was elected a Fellow of King’s College. This was followed in 1936 by a paper titled, On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, in whichhe reformulated Kurt Gödel’s results on the limits of proof and computation, He replaced Gödel’s universal arithmetic-based formal language with hypothetical devices now known as Turing machines. Turing proved that his “universal computing machine” would be capable of performing any conceivable mathematical computation if it were representable as an algorithm. By showing that the halting problem for Turing machines is undecidable he solved Hilbert’s tenth problem, proving that there is no algorithm for determining whether a diophantine equation has a solution.

From September 1936 to July 1938, Turing was at Princeton University, studying under one of the founders of computer science, Alonzo Church. In June 1938, he was awarded his PhD for his dissertation, Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals, in which he introduced the concept of ordinal logic. studied cryptology and also built three of four stages of an electro-mechanical binary multiplier.

During the Second World War, Turing was a leading participant in the breaking of German ciphers at Bletchley Park. The historian and wartime codebreaker Asa Briggs has said, “You needed exceptional talent, you needed genius at Bletchley and Turing’s was that genius.”[62]

In September 1938, Turing began work with the British Government Code and Cypher School, using cryptanalysis to crack the code of the Enigma cipher machine used by Nazi Germany. Building on information, provided by the Polish Cypher Bureau, about the wiring of the Enigma machine’s rotors and its method of encrypting messages, Turing and his team were able to break the Enigma code. This was a major contribution to the Allied war effort, as detailed in the book Alan Turing: The Enigma, and 71 years later in the 2014 movie, The Imitation Game.

Early in 1943, Turing met Claude Shannon over tea in the cafeteria of the Bell Labs. Turing shared with Shannon a paper he had published in 1936, outlining how a Universal Turing Machine could execute a series of instructions, composed only of 0’s and 1’s, to perform any mathematical or logical computation. By using electric circuits to simulate the 0’s and 1’s of symbolic logic, Shannon was able to represent logical reasoning electronically. This led to the use of switching circuits in computers and the creation of information theory, paving the way for the Internet 50 years later.

On June 8, 1954, Turing’s housekeeper found him dead. The autopsy ruled that he committed suicide by the ingestion of cyanide. There has been much speculation about the motivations that may have resulted in his decision to end his life.

When asked the question, “Can machines think?,” Turing responded, “A computer would deserve to be called intelligent if it could deceive a human into believing that it was human.” This later became known as the Turing test of intelligence.