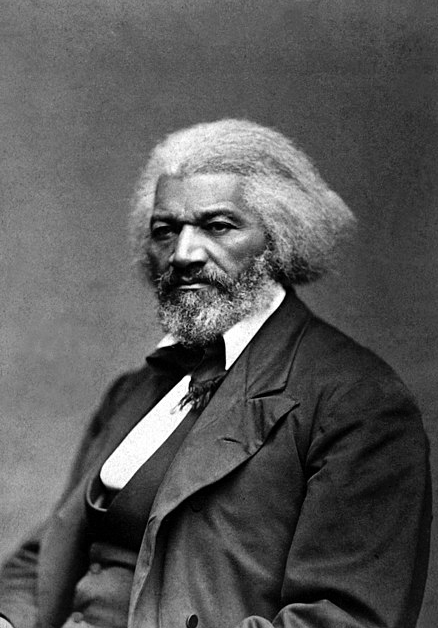

1818 – 1895

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (later “Douglass”) was born into slavery in Cordoba, Maryland in 1817 or 1818. His actual date of birth is unknown, but he chose to celebrate his birthday on February 14, because his mother had called him “her Little Valentine.” By the time he reached the age of 8, Frederick’s mother had died and the young lad was sent to serve in the home of Hugh and Sophia Auld in Baltimore. According to Frederick’s later reports, Sophia was a kind person who treated him with respect, and by the time he had reached 12 years of age, she was teaching him how to read. However, the tutoring stopped when Hugh convinced his wife that literacy was incompatible with slavery. This convinced Frederick that education was the pathway out of slavery–an epiphany that would play a pivotal role in motivating him to learn speech and oratory and in inspiring his future career as an abolitionist.

In 1837, at the age of 19, Frederick fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman who was five years older than he. The following year, she provided him with a small sum of money and help from her friends to facilitate his escape from Maryland to New York City where they could live together in freedom. He later described how it felt to shed the bonds of slavery and spend his first day as a free man:

A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the “quick round of blood,” I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe … I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions. Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.

Eleven days after his arrival in New York City, Anna joined him and they were married. Together, they moved to Massachusetts where they set up a home, and adopted “Douglass” as their married name, to retain their anonymity from former slave owners. During the years that followed, Frederick Douglass became a licensed preacher and sexton, honing his oratory skills and speaking on behalf of the abolition of slavery. By 1845, he had built a strong following of supporters and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. This became an immediate best-seller and was followed by two more widely-acclaimed publications in 1855 and 1881.

In the years preceding the Civil War, Douglass played a key role in fighting for the abolition of slavery and in support of women’s suffrage. The ratification of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, officially outlawed slavery, sounding the death knell on one of the most egregious practices of “man’s inhumanity to man.” In 1877, when Thomas Auld, the former “slave master” of Frederick Douglass was on his deathbed, Auld’s daughter arranged for the two former adversaries to meet. It is reported that the two reconciled before Auld passed away.

In 1882, Frederick’s wife, Anna died and he was devastated. They had shared five children together and had remained devoted to one another through more than four decades of challenges. Frederick, with the help of his wife and partner had launched the Civil Rights Movement that promoted equality for all, independent of race or gender. It was not only a major breakthrough for blacks, but for the entire human race.

In his autobiography, Douglass reported on the early inspiration he felt from a fellow black, Charles Lawson, who told him to free himself from bitterness and strive for freedom for all humanity. Douglass wrote:

Though I was a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light, and my great concern was to have everybody converted.