Edward Osborn Wilson was born on June 10, 1929 in Birmingham, Alabama. From an early age, he was interested in natural history, and brought home creatures, including black widow spiders, that his parents allowed him to keep on the porch of their modest home. Edward’s father was an alcoholic–an addiction that eventually led to a divorce that occurred when Edward, an only child, reached seven years of age. Eventually his father committed suicide.

A fishing accident during his youth cost Edward the vision in his right eye, and may have prompted him to focus on the minuscule world of insects, once observing, “I noticed butterflies and ants more than other kids did, and took an interest in them automatically.” Expeditions to Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC. led to a fascination with ants that he described as “short, fat, brilliant yellow, and emitting a strong lemony odor.” At age 18, wanted to become an entomologist, but the shortage of insect pins caused by World War II caused him to switch to ants, because they could be stored in vials. Eventually, he discovered the first colony of fire ants in the United States.

Perhaps recalling the distinctive scent of the citronella ants in Rock Creek Park, he discovered that ants communicate through pheromones, and he described the sophisticated social organization of these insects and the chemical determinants of their actions:

Ants organize their colonies with many chemical systems like those used to transmit alarm. Their bodies, we discovered, are walking batteries of glands filled with semiotic compound. When ants dispense their pheromones, singly or in combination and in varying amounts, they say to other ants, in effect: “danger come quickly; or danger, disperse; or food, follow me; or there is a better nest site, follow me; or I am a nestmate, not an alien; or I am a larva;” and on through a repertoire of ten to twenty messages, with the number differing according to caste (such as soldier, or minor worker) and species. So pervasive and powerful are these codes that they bind the colonies into a single operational unit.

In 1975, Wilson hypothesized that much of human ethics might be rooted in our chemistry, forged by evolution into group loyalty, protective behaviors, and altruistic tendencies. At that time, his theories were ignored or outright rejected by most of the social science community. At a symposium of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in February 1978, a group of protestors chanting, “Racist Wilson you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide!” stormed the stage of illustrious speakers and poured a pitcher of ice water over Wilson’s head.No charges were laid.

Undaunted, Wilson continued to link human behavior to genetics. About a quarter-century later, he asserted in his seminal book Consilience:

Each kind of animal is furthermore guided through its life cycle by unique and often elaborate sets of instinctual algorithms, many of which are beginning to yield to genetic and neurobiological analyses. With all these examples before us, it is not unreasonable to conclude that human behavior originated the same way.

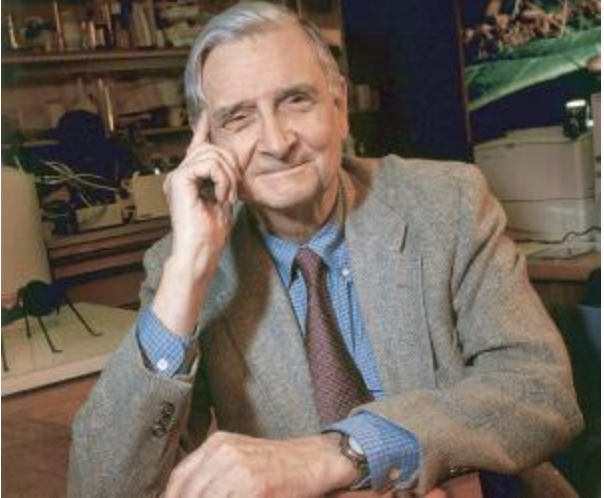

E. O. Wilson, a Harvard professor for 40 years, was one of the great visionaries of the 20th century, who received a long list of awards including two Pulitzer Prizes and a listing in Time Magazine in 1995 as one of America’s 25 most influential people. His theories were not challenged by facts, but by the opinions of those who were promoting an egalitarian ideology. In reference to ants, Wilson said, “Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species”.