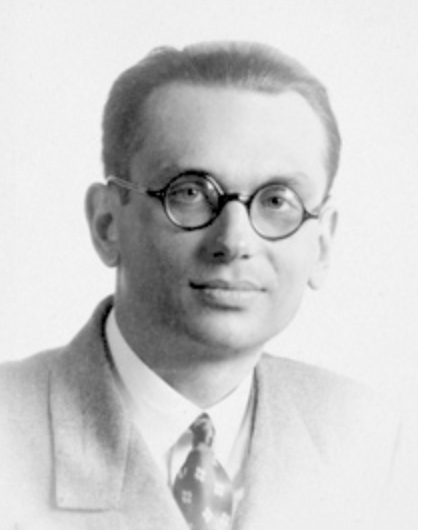

Kurt Gödel was born on April 18, 1906 in Brünn, Austria-Hungary. In 1931, at age 25, he published his doctoral thesis, On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems. In this epoch-making paper, Gödel proved an abstruse theorem that shook the foundations of mathematics. But even more abstruse and enigmatic than his theorem was Gödel himself. His biographer, Rebecca Goldstein writes:

Kurt Gödel struck almost everyone as seriously strange, presenting a formidable challenge to conversational exchange…John Bahcall was a promising young astrophysicist when he was introduced to Gödel at a small Institute dinner. He identified himself as a physicist, to which Gödel’s curt response was, ‘I don’t believe in natural science.

Following his permanent appointment to the Institute in 1946, Gödel decided to apply for citizenship. Taking seriously his preparation for the citizenship exam, Gödel pored over the US Constitution with a fine-tooth comb, when he stumbled upon what he believed to be an inconsistency that could allow the democracy to degenerate into a dictatorship. Princeton mathematician Oskar Morgenstern, recounted what has become one of the most popular anecdotes in the lore of eccentric mathematicians. It was December 5, 1947–the day that Einstein and Morgenstern accompanied Gödel to his citizenship exam.

On that particular day, I picked up Gödel in my car. He sat in the back and then we went to pick up Einstein at his house on Mercer Street…While we were driving, Einstein turned around a little and said, “Now Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Of course, this remark upset Gödel tremendously, which was exactly what Einstein intended and he was greatly amused when he saw the worry on Gödel’s face.

[When we arrived at the immigration office], we were invited to sit down together, Gödel, in the center. The examiner first asked Einstein and then me whether we thought Gödel would make a good citizen. We assured him that this would certainly be the case, that he was a distinguished man, etc.

And then he turned to Gödel and said, Now, Mr. Gödel, where do you come from?

Gödel: Where I come from? Austria.

The examiner: What kind of government did you have in Austria?

Gödel: It was a republic, but the constitution was such that it finally was changed into a dictatorship.

The examiner: Oh! This is very bad. This could not happen in this country.

Gödel: Oh, yes, I can prove it.

So, of all the possible questions, just that critical one was asked by the examiner. Einstein and I were horrified during this exchange; the examiner was intelligent enough to quickly quieten Gödel and broke off the examination at this point, greatly to our relief.

In the decades that followed, Kurt Gödel showed increasing signs of paranoia and, suspecting that his food was being poisoned, he continued to restrict his eating. On December 29, 1977, Gödel entered Princeton Hospital at an estimated weight of sixty-five pounds and died on January 14, 1978. The death certificate stated that he died of “malnutrition and inanition” caused by “personality disturbance.”

In 1978, an article in The New York Times described Gödel’s Theorem as “the most significant mathematical truth of this century, incomprehensible to laymen, revolutionary for philosophers and logicians.” A symbol-free expression of this theorem and its corollary can be found in the book, Intelligence: Where we Were, Where we Are, & Where we’re Going.