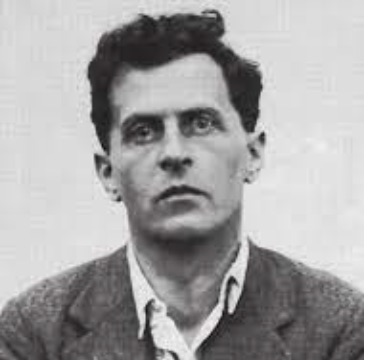

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein was born on April 26, 1889 in Neuwaldegg, Vienna, Austria-Hungary, into the second wealthiest family in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was the youngest of 9 children in a family immersed in an intensely intellectual culture. Johannes Brahms was a frequent guest of the Wittgensteins. Famous orchestra leader Bruno Walter once described the Wittgenstein palatial environment as an “all-pervading atmosphere of humanity and culture.” The intensity of that environment and the negativity it generated was later manifest when three of Ludwig’s five brothers committed suicide.

Ludwig’s father, Karl, was an industrial magnate who had acquired huge wealth in the steel industry and wanted his sons to become executives in his own industrial complex. Fearing that the influence of other children might diminish their discipline, he kept them out of schools and had them tutored at home. Ludwig was home-schooled until he was 14 years old. When he entered school at age 14, Ludwig was unfamiliar with school protocols, socially inept and ridiculed by the other students. His grades were not exceptional.

On October 23, 1906, he enrolled in mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule Berlin, graduating on May 5, 1908 with a diploma. He subsequently developed an interest in aeronautics and by 1911 had a patent for a special propeller blade with engines on its tip. However, Ludwig was not adept at turning his ideas into practical applications and his interests soon moved into more theoretical topics.

In 1911, Ludwig Wittgenstein, perceived by many as a wildly eccentric Austrian, came to Cambridge University to study mathematical logic under the mentorship of Bertrand Russell. Inspired by the works of Frege and Russell, the tempestuous young scholar sought to resolve, once and for all, the kinds of paradoxes that had bedeviled formal logic. At first, Wittgenstein’s irate rants, and outrageous declarations convinced Russell that his acolyte was either an idiot or a genius. However, after reading his written work, Russell decided in favor of the latter, stating:

He was perhaps the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating … He used to come to see me every evening at midnight, and pace up and down my room like a wild beast for three hours in agitated silence. Once I said to him: “Are you thinking about logic or about your sins?” “Both,” he replied, and continued his pacing. I did not like to suggest that it was time for bed, as it seemed probable both to him and me that on leaving me he would commit suicide.

During their work together, Wittgenstein began to view Russell’s work with a degree of contempt. His severe criticism of Russell’s writings on the Theory of Knowledge sent the mentor into a depression that he later expressed in a letter to Lady Ottoline Morrell:

His [Wittgenstein’s] criticism, tho’ I don’t think you realized it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy. My impulse was shattered, like a wave dashed to pieces against a breakwater.

Wittgenstein went to Norway in 1913, where he attempted to explore the foundations of logic, and hoped to find a method for identifying which statements in logic are tautologies and which are contradictions. He believed that most contradictory statements derive from the vagueness of natural language and he sought a propositional calculus that would identify by computation whether a given proposition was consistent or inconsistent with basic premises. Building on the work of Leibniz, Boole, Frege, and others he displayed logical propositions in a tabular format, called a truth table, that became a powerful device in the development of the calculus of symbolic logic.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Wittgenstein voluntarily joined the Austro-Hungarian army, fighting against Britain and its allies. During this period, he continued working relentlessly on what would become his grand opus. His strong patriotic feelings and his willingness to accept death made him a fearless fighter, and won him promotions and numerous military honors. In 1918, he was captured and became a prisoner of war. After his release, he arranged to meet Russell at the Hague where they would discuss Wittgenstein’s new opus for which Russell would write an introduction. However, Wittgenstein didn’t have enough money to fund his transportation from Austria because he had earlier donated to his siblings the fortune he had inherited from his father–believing that philosophers have no need for money. Russell agreed to accept the furniture and library that the young scholar had left behind at Cambridge in return for paying the idealistic philosopher’s travel expenses.

Shortly after the end of the War, Wittgenstein returned to Austria in a state of deep depression and spoke often of suicide–a course of action taken by 3 of his 5 brothers. After his period of depression, he left philosophy and became an elementary school teacher in a remote Austrian village. He fought with the other teachers, rode his students heavily–caning the boys and pulling the girls’ hair when they failed to grasp a concept. For the top students, he worked tirelessly, but for the bottom students, he was a nightmare.

In 1921, during the decade that he was teaching in various elementary schools in Austria, his work, published in German under the title, Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung came to the attention of the famous Vienna Circle of philosophers. The following year, it was published with the title Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. This eventually brought him celebrity and led to his appointment as lecturer and fellow of Trinity College at Cambridge, where he founded the field of philosophy subsequently known as logical atomism.”

In 1947, Wittgenstein resigned from his professorship at Cambridge so that he could devote his full time to writing. He travelled first to Ireland, then to America and back to London where he was diagnosed in 1950 with inoperable prostate cancer. Two days after his 62nd birthday, he lay in bed at his doctor’s home in a semi-conscious state and knowing death was imminent, uttered, “Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.” He passed away a few hours later.