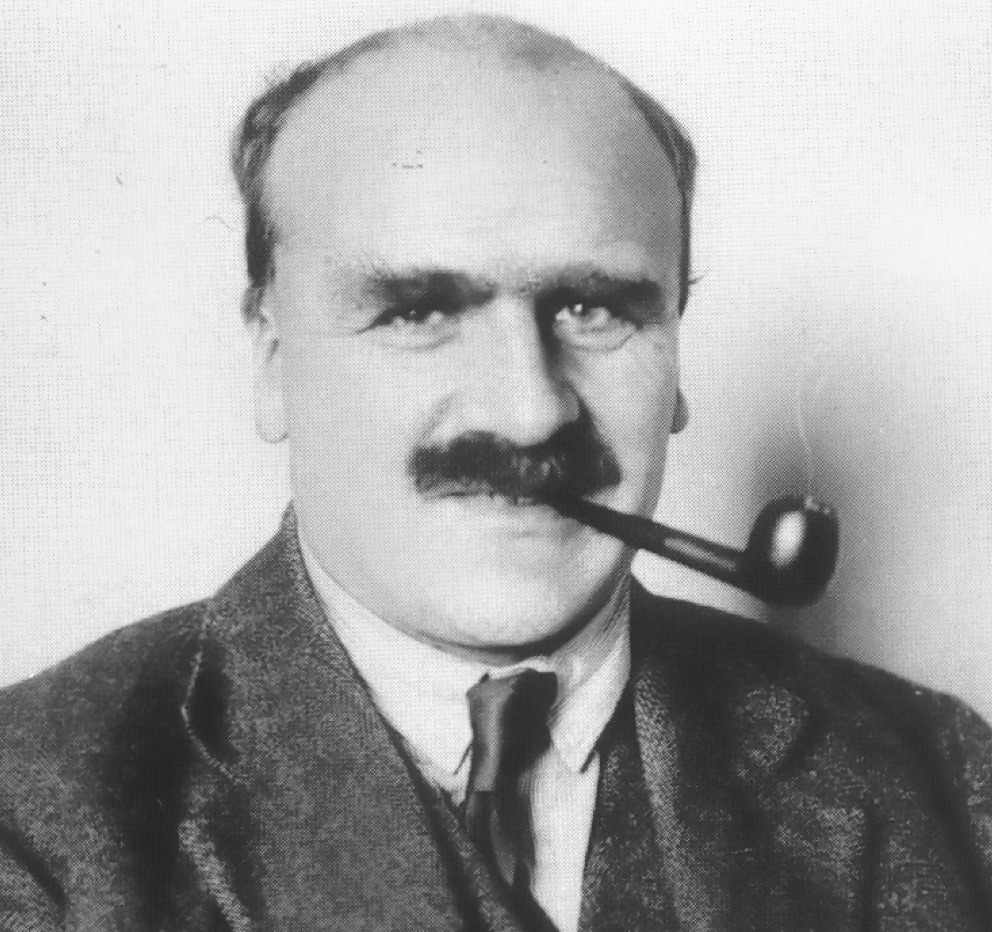

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, commonly, known as J.B.S. Haldane, was born on November 5, 1892, in Oxford, England. His father, John Scott Haldane was a physiologist and a philosopher, his mother, Louisa Kathleen Trotter was from Scottish ancestry. J.B.S. learned to read when he was 3 years old.

In 1897, at five years of age, J.B.S enrolled at Oxford Preparatory School, where he would eventually gain a First Scholarship to Eton. In 1899, the Haldane family moved to “Cherwell”, on the outskirts of Oxford where they had their own private laboratory. When J.B.S was 8 years old, his father introduced him to the Oxford University Junior Scientific Club where the young aspiring scientist learned about the early discoveries of Mendelian genetics. Although the young lad hadn’t understood the details of the lecture, he was inspired to learn more about the exciting world of genetics and intelligence. During this time, J.B.S. explored chemistry with his father in their home laboratory. They became “human guinea pigs”, in their exploration of the effects of poison gases, as they sometimes tested chemicals on themselves.

In 1905 J.B.S. enrolled at Eton, to which he had earned a scholarship, but he soon experienced bullying from senior students for his perceived arrogance. His indifference to authority left him with a lasting hatred for the English education system. However, the ordeal did not stop him from becoming Captain of the school.

Participating in research in those areas where his father had engaged in discovery, J.B.S. studied the effects of the “bends,” experienced when goats lift and bend their legs. This research provided significant insight into the effects experienced by deep-sea divers. In July 1906, young Haldane jumped into the Atlantic Ocean in an experimental diving suit, and became the first to study the effects of decompression on humans.

In 1908, the results of this study were published in a 101-paged article in The Journal of Hygiene describing him as “Jack Haldane (age 13) who had never before dived in diving dress,” and proclaiming him as the founder of a new scientific theory that would be known as Haldane’s decompression mode.

In 1912, at 20 years of age, Haldane graduated with first-class honors in his study of mathematics and classics at New College, Oxford. After graduation, he became engrossed in genetics and, in 1912, presented a paper on gene linkage. His first technical paper, a 30-page article on haemoglobin function, co-authored with his father, was published in December 1913 in the Proceedings of the Physiological Society.

Haldane did not want his education to be confined to a specific subject. He engaged in a program known as “greats” that covered a range of subjects and he graduated with first-class honours in 1914. Haldane’s intention to study physiology, was subverted by World War II, preventing him from receiving formal education in vertebrate anatomy.

To support the war effort, Haldane joined the British army and on August 15, 1914 was commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Highland Regiment, known as the “Black Watch” Haldane was assigned as trench mortar officer, to lead his team for hand-bombing of the enemy trenches. In his article in 1932, he described how he “enjoyed the opportunity of killing people and regarded this as a respectable relic of primitive man.” He was promoted to temporary lieutenant on February 18, 1915 and to temporary captain on October 18 of that year.

While serving in France, Haldane was wounded by an artillery fire, resulting in his return to Scotland where he served as instructor of grenades for the Black Watch recruits. In 1916, he joined the war in Mesopotamia (Iraq) where he was severely wounded from an enemy bomb. Relieved from serving on the war front, Haldane was sent to India where he remained for the rest of the war. In 1919, Haldane returned to England, and relinquished his commission. For his ferocity and aggressiveness in battles, his commander described him as the “bravest and dirtiest officer in my Army.”

Between 1919 and 1922, Haldane served as Fellow of New College, Oxford, where he conducted research in physiology and genetics, despite his lack of formal education in the field. During his first year at Oxford, he published six papers dealing with physiology of respiration and genetics, and then, shortly after, moved to the University of Cambridge where he accepted a readership in biochemistry. His tenure at Cambridge spanned the years form 1923 to 1932. It was during this 9-year hiatus that Haldane worked on the mathematical models of genetics, especially as they pertained to enzymes.

In the decade spanning 1927 to 1937, Haldane was engaged in research at the John Innes Horticultural Institution. He became Fullerian Professor of Physiology at the Royal Institution from 1930 to 1932 and in 1933, had become Professor of Genetics at University College London, until retiring in 1939. Meanwhile, Haldane’s service was recorded to have helped the John Innes Horticultural Institution to become, “the liveliest place for research in genetics in Britain.” Between 1941 and 1945, at the height of World War II, Haldane moved his team to the Rothamsted Experimental Station in Hertfordshire to escape bombings..

In 1956, Haldane left University College, London to join the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Calcutta, India, where he worked in the biometry unit. Haldane gave many reasons for moving to India, officially attributing his migration to the Suez Crisis, He stated, “Finally, I am going to India because I consider that recent acts of the British Government have been violations of international law.” He believed that the warm climate would be beneficial to his health and he could enjoy it in a country that shared his socialist dreams.

In an article “A passage to India” which he wrote in 1958, titled The Rationalists Annual, he stated: “For one thing I prefer Indian food to American. Perhaps my main reason for going to India is that I consider that the opportunities for scientific research of the kind in which I am interested are better in India than in Britain, and that my teaching will be at least as useful there as here.” Meanwhile, the university had terminated his wife’s employment for drunk and disorderly behavior and she had refused to pay a fine, triggering Haldane’s resignation. He declared he would no longer wear socks, “Sixty years in socks is enough” and thereafter dressed in Indian attire.

In February 1964, Haldane was diagnosed with colorectal cancer that progressed aggressively through that year. On December 1, 1964, J.M.S. Haldane died in Bhubaneswar, India. J.M.S. Haldane made groundbreaking contributions to the field of genetics, particularly in the areas of natural selection, population genetics, and the mathematical foundation of evolutionary biology. His work on genetic linkage and recombination was fundamental to our understanding of how traits are inherited. In 1946, Haldane stressed the importance of environment in enabling a person to reach their intellectual potential:

We cannot in general say that A has a greater innate ability than B. A might do better in environment X, and B in environment Y. Had I been born in a Glasgow slum I should very probably have become a chronic drunkard, and if so, I might by now be a good deal less intelligent than many men of a stabler temperament but less possibilities of intellectual achievement in a favourable environment. If this is so it is clearly misleading to speak of the inheritance of intellectual ability. This does not mean that we must give up the analysis of its determination in despair. It means that the task will be harder than many people believe.

Many of his contemporaries remember Haldane as an extremely intelligent person, and Nobel laureate Peter Medawar once referred to Haldane as, “the cleverest man I ever knew”