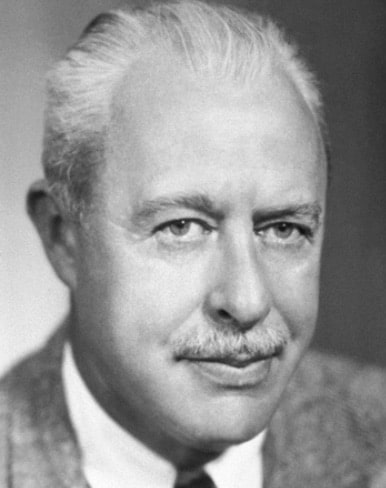

Walter Houser Brattain was born on February 10, 1902 in Xiamen, Fujian Qing China where his father was a teacher at the Ting-Wen Institute, a private school for Chinese boys.. Walter’s parents were graduates of Whitman College in Washington State and his father was a gifted mathematician When Walter was a year old, he moved with his mother Ottilie to Spokane, Washington and they were joined shortly after by his father. In 1911, the family moved to a cattle ranch in Washington. Walter’s early education was obtained through his attendance at a several schools in Washington State. In 1924, at the age of 22, Walter received his B.Sc. graduating with a double major in mathematics and physics from Whitman College. Two years later, he earned a Master of Arts from the University of Oregon at Eugene and in 1929, he was awarded a Ph.D. in the emerging field of quantum physics from the University of Minnesota. His thesis, titled Efficiency of Excitation by Electron Impact and Anomalous Scattering in Mercury Vapor was supervised by physicist John Tate.

During his postgraduate work, Brattain worked for the National Bureau of Standards in Washington D.C. where he helped developed standards for piezoelectric frequencies. (Piezoelectricity is the charge that is generated when pressure is applied to certain substances such as crystals and bones.) His research on the photoelectric properties of the surfaces of semiconductors such as silicon paved the way for the transition from the less reliable vacuum tubes to crystal semi-conductors to amplify electric currents..

In 1929, Brattain was employed as a researcher at Bell Telephone Laboratories where he subsequently worked with William B. Shockley on using semiconductors for amplification of electric current. During World War II, he served on the National Defense Research Committee at Columbia University exploring techniques for the detection of submarines. After the War, Bell Labs convened a team of researchers headed by Shockley that included John Brattain and John Bardeen, a brilliant quantum physicist, to explore semiconductors –an exploration that eventually led to the discovery of transistors.

On December 23, 1947, the team of three brilliant researchers at Bell Labs demonstrated the first of a series of functioning transistors. Less than a decade later, Shockey, Brattain and Bardeen were jointly awarded the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for their groundbreaking discovery of the transistor effect. At the Nobel Award ceremony, Brattain graciously stated, “I certainly appreciate the honor. It is a great satisfaction to have done something in life and to have been recognized for it in this way. However, much of my good fortune comes from being in the right place, at the right time, and having the right sort of people to work with.” In the years that followed, Brattain had a distinguished academic career, holding positions at various institutions, including Bell Labs, Whitman College, and the University of Washington. In those roles, he mentored numerous students and researchers.

John Brattain retired from teaching in 1976, but continued to serve as a consultant. On October 13, 1987, following a long struggle with Alzheimer’s, he passed away in Seattle, Washington. His pioneering work in solid-state physics and semiconductor research, laid the foundation for the modern electronics industry–contributions that continue to have a profound impact on technology and society.