In November 15, 1927, Einstein’s long tribute to Newton on the bicentenary anniversary of his death, began with the statement:

One’s thoughts cannot but turn to this shining spirit, who pointed out, as none before or after him did, the path of Western thought and research and practical construction. He was not only an inventor of genius in respect of particular guiding methods; he also showed a unique mastery of the empirical material known in his time, and he was marvelously inventive in special mathematical and physical demonstrations. For all these reasons he deserves our deep veneration. He is, however, a yet more significant figure than his own mastery makes him, since he was placed by fate at a turning point in the world’s intellectual development. This is brought home vividly to us when we recall that before Newton there was no comprehensive system of physical causality which could in any way render the deeper characters of the world of concrete experience.

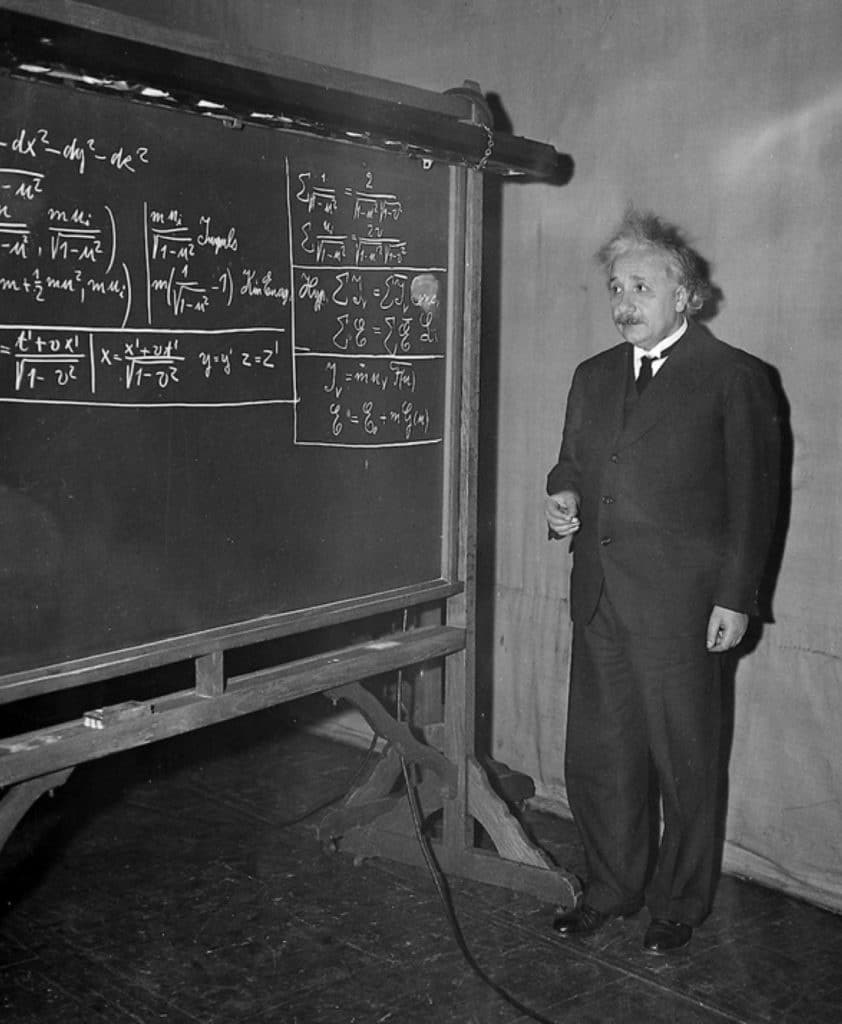

The long and detailed tribute from Einstein extends for many pages as Einstein explains the evolution of science and physics from the time of Galileo, through Newton and beyond. About Galileo, Einstein stated:

Propositions arrived at purely by logical means are completely empty as regards reality. Because Galileo saw this, and particularly because he drummed it into the scientific world, he is the father of modern physics–indeed, of modern science altogether.

Einstein was always lavish in his praise of other scientists he respected and was extremely supportive of young scientists who needed references. It was not in his personality to compare his intelligence to others because he recognized that all great scientists are highly intelligent and that is expressed in different ways by different people. Einstein’s strength was his intuition and the originality of his thinking–something he referred to as “originality.” His weakness was in mathematics and he sought help from other mathematicians in expressing his General Theory of Relativity.

On one occasion when a young girl confessed having problems with mathematics, he attempted to encourage her by saying, “I assure you that your difficulties in mathematics are no greater than mine.” Einstein was a gracious person when speaking of himself, but his humility was also accompanied by a strong sense of self efficacy that prompted him to argue strongly for determinism in the face of contradictory quantum phenomena like entanglement.