Yes, a significant proportion of those brilliant people who defied consensus opinion were considered crackpots before their insights produced results. There is only enough space in this response to go into detail on one example, but I will provide links to brief bios of some others at the end of this post.

At the beginning of the 20th century, virtually everyone travelled in horse-drawn carriages. Thousands of people were employed as blacksmiths, replacing the shoes of horses that pulled carriages to deliver people or milk. The concept of a car, a carriage that could drive itself, was outside the imagination of the average citizen.

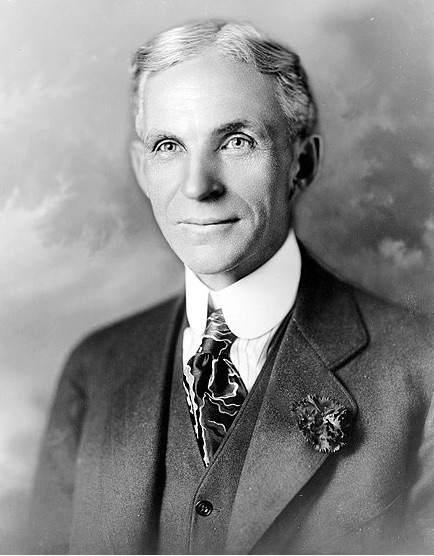

Then, in 1896, a school dropout named Henry, building on skills acquired as an engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit, MI decided to build his own engine and house it in a “horseless carriage.” By 1903, he had founded a corporation that was dedicated to building these newly configured “horseless carriages” for the masses.

When the early models appeared on roads made for horse travel, people ran behind these vehicles chanting, “Get a horse!” How could a carriage possibly move by itself without a horse pulling it? To make cars affordable for the working class, Ford realized that he had to reduce costs by increasing the efficiency of production. To achieve this, he instituted the moving assembly line, whereby workers installed car parts on the chassis as it moved past at a fixed rate. This moving assembly line revolutionized production methods and ushered in a new era of mass production.

As “Henry Ford” became a household name, the automobile visionary received growing criticism. The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times initially criticized Henry for his low wages and assembly lines, and later for his low prices. His shareholders, who were also at odds with his ideology, launched a series of lawsuits to block the implementation of his vision.

Having come from working class beginnings, Henry Ford identified with his employees and set the hourly wages higher than those typically paid for unskilled work. He also reduced the number of hours of labor below the standard work week, providing each worker with more time off for rest or leisure. When he reduced the price of his cars below their cost, his Chief Financial Officer quit and filed a lawsuit, announcing to the press that Henry had gone mad. The press called him “mad Henry.” The suit alleged that Ford’s moves were self-serving and contrary to the best interests of the shareholders. But Ford was striving toward higher ideals and longer-term goals. He was prepared to lose in the short run for long-term gain. He felt that by reducing the prices of his cars so that everyone could afford them, and simultaneously raising the worker wage, he would be seeding his own market.

Gradually, the efficacy of Ford’s innovations became apparent. Their success was manifest in the growth of the Ford Motor Company from a firm with a nominal capitalization of $100,000 in 1903 to a behemoth with a surplus of $700 million in 1927. In the two decades between 1908 and 1927, exactly 15,458,781 Model T cars rolled off Ford’s assembly lines. The Model T had established itself as the car for the masses. In the process, Ford established himself as the father of modern mass production and a founder of the auto manufacturing industry. More importantly, Ford’s “democratization” of the automobile had profound long-term implications for the social fabric of America through the creation of a middle class. Henry Ford was a man with a vision who was considered “mad” until the world saw his success.

Visionaries like Henry Ford, throughout history, have been ridiculed, persecuted, or executed for their divergent thinking. Galileo, whom Einstein described as “the father of science” was convicted of heresy and put under house arrest until his death (See Sobell Dava. (2000) Galileo’s Daughter. Penguin Books). Father Gregor Mendel failed the oral exams that were a requirement to teach biology and his discovery of the laws of genetics went unnoticed until decades after his death. Einstein was originally considered a radical by the physics community and his theories were dismissed as “Jewish physics.” Even though he made outstanding discoveries in 1905, he was not to receive a Nobel Prize for another 15 years. These visionaries didn’t metamorphose from “crackpot” to genius, by changing their beliefs; they remained consistent throughout. It was public perception that changed as those without the vision witnessed what they never believed possible.