It would seem that someone of IQ > 160 would have a much greater likelihood of having lifestyle options not available to someone of IQ < 100, and yet within each group there are people whose lifestyles range from miserable to highly rewarding. If we were able to measure the quality of lifestyle and experiences on a Likert scale from 1 to 10, for each of these two IQ groups, we would find that the “between-group variance” in the measures would be significantly less than the “within-group variance.” That is, the differences in the quality of lifestyle among individuals in the same IQ group would be much greater than the difference in the average lifestyle quality of each group.

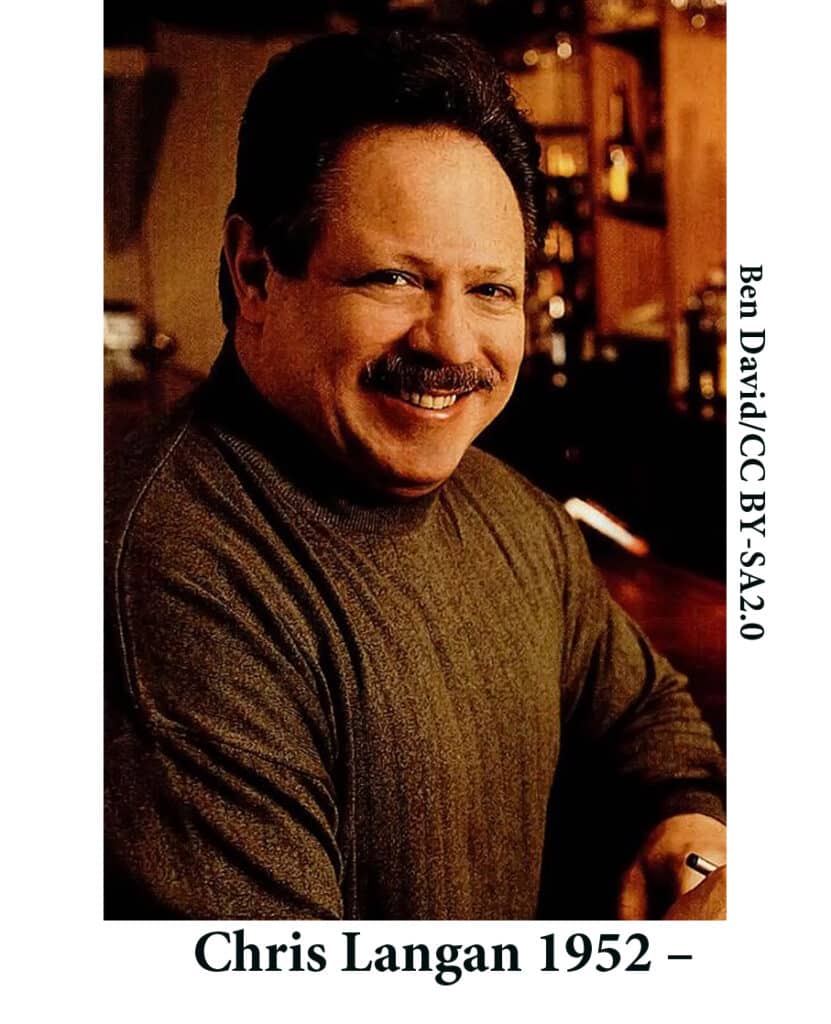

At 8:00 p.m. EST on January 25, 2008, millions of Americans tuned in to watch “the smartest man in America” take on 100 other contestants in a trivia contest. The cameras panned in on host Bob Saget as he announced, with exploding enthusiasm, “It’s the 1 vs. 100!” The guest who challenged the 100 other contestants (called the “mob”) was Chris Langan deemed “the smartest man in America.” Hyping the status of the special guest, Saget observed, “The average person has an IQ of 100, … Einstein, 150. Chris has an IQ of 195.”

During that television program, Langan answered a succession of questions that netted him $250,000. This was a lot of money for him, because his life had been fraught with a series of misadventures, poor choices and missed opportunities. He came to the television show as a highly intelligent man, earning a modest living from his ranch in Missouri. Acknowledging that he’s never been interested in accumulating wealth, Langan explained in an ABCNEWS feature posted on December 9, 1999:

There’s no logical connection between being smart and having money. Now, being smart helps if you want to have money. But if you aren’t necessarily focused on getting money in the first place, there’s no reason smarts should make the money roll in.

From his interview of three other people of exceptionally high IQ, Mike Sager of Esquire Magazine* described three other people of exceptionally high IQ who were also of modest means. All of them had experienced difficulty fitting into normal society. All three of them faced in their early years, bullies, resentment, and the ostracism that comes from being different.

One of these was Ronald K. Hoeflin, described by Sager as a “mild man with graying hair, who is 55 years old, legally blind, and living alone with three cats.” Reflecting on his social awkwardness, Hoeflin recalled an incident in the sixth grade when a girl in his class invited everyone to her birthday party. On his arrival, he was devastated when the birthday girl exclaimed, “I didn’t expect you to come.” Throughout his life, Ron struggled with acceptance, admitting:

The truth is that people with average intelligence are all a bit resentful. Throughout their entire schooling, they’ve had to compete with these people who seem to find it easy to get straight A’s, and they’re working hard just to get B’s and C’s. …It’s like you’re born out of sync with the world and you just have to adjust.

Ron has an IQ of 165, a level reached by only about one out of every 136,000 people. He is credited with the creation of two of the world’s most difficult IQ tests–the Mega and Titan. Though he has two bachelor’s degrees, two master’s degrees and a Ph.D, in philosophy, Ron lives on an annual income of about $7000, paying a monthly rent of about $106 in Hell’s Kitchen, New York. When asked whether his impecuniosity was a problem, he responded:

It’s a trade-off. Money on one hand, leisure and independence on the other. I’m not really enough of a people person to become wealthy, so I figure, what the heck, you know? I’m used to my condition. I have food and shelter and clothing. You don’t have to be a genius to know that those are the most important things of all.

Another of these Hi-Q people of modest means is Gina LoSasso, described by Sager as a “short, garrulous woman with a heavy Brooklyn accent, purple eye shadow and an IQ of 168,” who at 43 years of age was a twice-divorced mother of two. During her school years, Gina felt self-conscious and her fear that she would be regarded as a nerd, prompted her to misbehave, often skipping school to run with the fast crowd. By age 14, she was in a residential drug-treatment program. Gina is a self-described obsessive-compulsive, who admits to an obsession with puzzles and games, including Scrabble and chess–an addiction that brought Gina to the top of the chess world. In 1986, she was chosen as a member of the U.S. Chess Olympic Team that competed in Dubai.

Throughout her early life, Gina had fled from what she regarded as mundane and tedious. Consequently, she flunked out of three different colleges and ran the gamut of unskilled jobs from selling copy machines to serving popcorn in movie theaters. However, once Gina focused on a goal, she could harness her OCD to a productive end. In a period of 5 years, she was able to earn three degrees, the final one a Ph.D. in clinical neuropsychology from Wayne State University. Shortly after, she moved to Connecticut where she pursued postdoctoral studies at Norwalk Hospital.

Throughout her entire life, Gina chased the dopomine high that comes from solving a puzzle, winning a chess game, or partying with friends. Accumulating wealth never seemed to appear on her radar screen. As she said to Mike Sager:

Look at all the fun I’ve had. I’ve partied a lot. I’ve dined with heads of state and heroin addicts…I’m very philosophical about my whole experience growing up in an inner city and struggling and being different, because I’m here now, and I’m at a really good point.

Prior to her move to Connecticut, Gina had been corresponding with Chris Langan, “the smartest man in America.” Romantic e-mail exchanges between these two Hi-Q people soon blossomed into a serious relationship. By 2004, Gina LoSasso had become Mrs. Gina Langan, sharing life with Chris on a horse farm in Mercer, Missouri.

There are high IQ people who go to the prestigious schools, get A’s and go into academe, a profession, or the corporate world. Other Hi-Q people chase fulfilment in non-traditional ways, through music, chess, or competitive sport. Still other Hi-Q people aspire to neither wealth nor prestige; in some cases, their special gifts have alienated them from society, causing them to seek peace in relative isolation. These three types of Hi-Q people, who have no interest in pursuing a high income or accumulating wealth, result in a lower correlation between IQ and wealth, as do those of moderately high IQ who accumulate wealth that is magnitudes greater than most Hi-Q people.

*Sager, Mike. “The Smartest Man in America.” Esquire Magazine. Nov. 1999.