Brilliant people are often characterized as socially inept because they often display behaviours that transcend normalcy. The brilliant physicist, John von Neumann, was known for his quirky behaviors, such as standing at the bottom of a staircase and looking up the dresses of woman as they walked upstairs. Yet, in certain social circles, he entertained people with what were considered “dirty jokes” which he told in several different languages. The biography of John von Neumann, posted by the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, states:

Von Neumann is remembered as a man of warm personality: courteous, charming, and jovial, with an often ribald, sometimes wry, sense of humor that made him excellent company and gained him a reputation as a bon vivant. He was fond of limericks and practical jokes and hosted frequent Princeton parties. He was also well known as a reckless driver, once emerging, so the story goes, from a smashed car with the explanation: “I was proceeding down the road. The trees on the right were passing me in orderly fashion at 60 MPH. Suddenly, one of them stepped out in my path. Boom!”

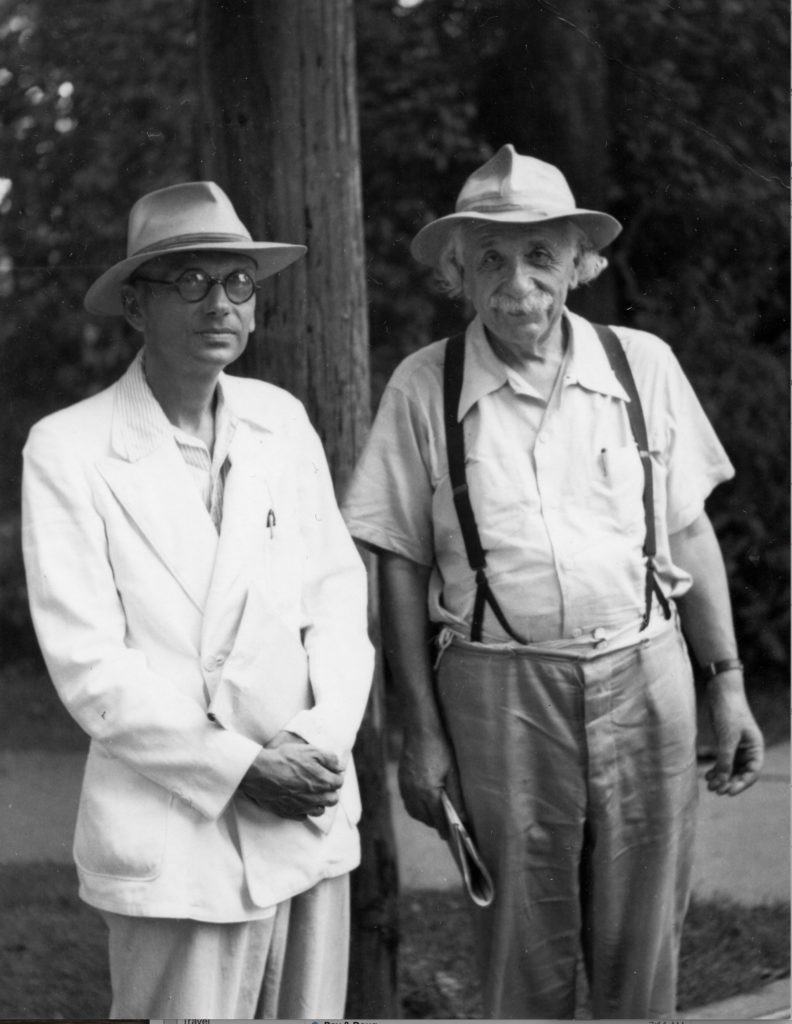

Similarly, Albert Einstein was considered very personable and convivial among a select group of physicists, but would have been considered socially inept among a group of normal people. He was not a social animal, and the role of his second wife, Elsa was to screen his potential visitors. Albert was inattentive to her needs and the needs of his children. His biographer Ronald Clark, in Einstein: The Life and Times, (pp.646–647) reproduced part of Einstein’s letter to his friend sent shortly after Elsa’s death:

I have settled down splendidly here. I hibernate like a bear in its cave and really feel more at home than ever before in all my varied existence. This bearishness has been accentuated further by the death of my mate, who was more attached to human beings then I.

There are many examples of geniuses who could be socially acceptable among colleagues, but were introverts who would appear socially inept in groups of normal people. The reason for this is simple: one must be different to make a difference. Those who see the world differently from others will have different interests, different perspectives and a different sense of humour than most people. The domains in which they can function well socially are usually limited to people who share some of their interests.

Then, there are the geniuses who are so different from others that they are socially inept in almost any group. In her book about Gödel and his theorem, Rebecca Goldstein writes:

Kurt Gödel struck almost everyone as seriously strange, presenting a formidable challenge to conversational exchange…John Bahcall was a promising young astrophysicist when he was introduced to Gödel at a small Institute dinner. He identified himself as a physicist, to which Gödel’s curt response was, ‘I don’t believe in natural science.”

So, it seems that brilliant people are usually most comfortable among other highly intelligent people and are not likely to be the life of a tailgate party. Some of them can be socially fluent in groups of higher intelligence while others are socially inept in almost any group.