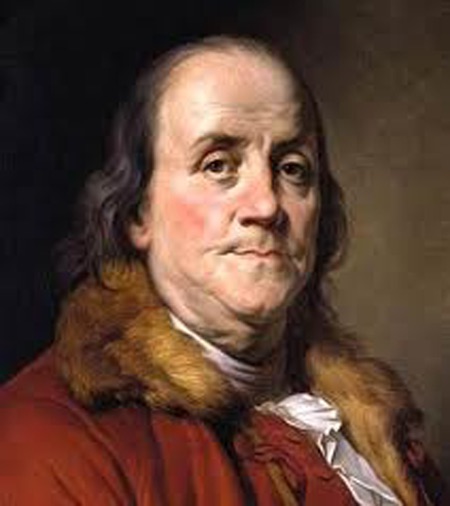

Ben Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 17, 1706, His family’s limited financial resources had forced him to drop out of Boston Latin school at age 10, and he subsequently found work as a printer’s apprentice. At age 17, he left Boston for Philadelphia where he continued to work in the printing business as a typesetter. During this period of his life, he educated himself by reading every book he could secure and participating in discussion groups.

In 1728, at the age of 22, he established a printing house and the next year became publisher of The Pennsylvania Gazette. In this capacity, he found an opportunity to instruct his readers on the importance of virtue and moral values, that he had absorbed through his Puritan roots. Between 1732 and 1758, he published his reflective insights as aphorisms in annual issues of The Poor Richard’s Almanack under the pseudonym “Richard Saunders.” Many of these aphorisms have become part of the fabric of American culture. Among the most familiar are:

- “There are no gains without pains.”

- “A penny saved is twopence dear.” (Often misquoted as “a penny saved is a penny earned.”)

Franklin’s advice to those who wish to achieve success is captured in a rather long aphorism that he himself modeled throughout his life:

In studying law or physick, or any other art or science, by which you propose to get your livelihood, though you find it at first hard, difficult and unpleasing, use diligence, patience and perseverance; the irksomeness of your task will thus diminish daily, and your labour shall finally be crowned with success. You shall go beyond all your competitors who are careless, idle or superficial in their acquisitions, and be at the head of your profession. Ability will command business, business [will command] wealth; and wealth an easy and honourable retirement when age shall require it.

Applying this philosophy to his own aspirations, Ben ventured into a wide range of intellectual pursuits. From his late 20’s and into his 40’s he studied a variety of subjects, including meteorology, oceanography, physics, and demography. In 1751, he wrote an essay showing that the doubling time for the US population was 20 years and he linked the population doubling time of a nation to its supply of food and land. This publication influenced the work of economists Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus, earning Ben status as a visionary and world class demographer.

After age 40, Ben Franklin began exploring the properties of electricity. Believing that lightning was an electrical discharge from the clouds, he proposed flying a kite in a thunderstorm to test his conjecture. In the folklore of early America, he is said to have carried out this experiment in 1752 while standing on an insulated pad to avoid electrocution. Whether true or not, it is known that his experiments with lightning led to his invention of the lightning rod. He is also credited with the invention of bifocal lenses, the Franklin stove, and the urinary catheter–a variation of the lightning rod. His practical scientific inventions won him international prestige in the scientific community and in 1756, at age 50, he became one of the few 18th-century Americans to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Entering the Wisdom Years

As Ben Franklin moved through his 40’s, he became increasingly involved in politics. By age 43, he was serving as Justice of the Peace for Philadelphia, at age 45 he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly, and by age 47 he had become the deputy postmaster-general of British North America. As a member of the PennsylvaniaAssembly, he went to England in 1759 to protest the Penn family’s administration of their proprietary rights in thecolonies. While in England, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of St. Andrews for his contributions to science. Henceforth, he was often addressed as Dr. Franklin.

In 1765 Britain passed the Stamp Act, levying a tax on the colonies that they regarded as “taxation without representation.” This intrusion on their sovereignty ignited a growing call for independence from Britain. In the years that followed, Franklin visited England, hoping to use his diplomatic skills to negotiate a more equitable economic relationship between Britain and the colonies–until he traveled across the Irish Sea.

During an excursion to Ireland in 1771, Dr. Franklin enjoyed the unprecedented honor of attending a session of the Irish Parliament. Reporting on his trip in a letter to Thomas Cushing, the speaker of the Massachusetts General Court, Franklin observed:

Ireland is itself a poor country, and Dublin a magnificent city; but the appearances of general extreme poverty among the lower people are amazing. They live in wretched hovels of mud and straw, are clothed in rags, and subsist chiefly on potatoes. Our New England farmers, of the poorest sort, in regard to the enjoyment of all the comforts of life, are princes when compared to them.

He realized that the abject poverty of the Irish was due in part to the harsh trade regulations imposed by Britain–the very same regulations that were threatening to cripple the economy of the colonies. This influenced profoundly his view of the relationship between the colonies and Britain. When it was realized that Franklin was sympathetic to the colonial cause, he was dismissed from his job as deputy postmaster-general for British North America. He left England in March 1775, arriving in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, just two weeks after the Battles of Lexington and Concord had launched the American Revolution.

In June 1776, at the age of 70, Franklin, who had been chosen as Pennsylvania’s delegate to the SecondContinental Congress, was appointed to the Committee of Five, that would draft the Declaration of Independence. During this period, he was suffering from gout and related maladies, but he agreed to perform an editing function. Franklin’s protégé and committee chair, Thomas Jefferson, at 33 years of age, had been chosen to write the first draft. When, at last, the document had been vetted by John Adams, Jefferson handed it to the eminent senior statesman with the words, “Will Doctor Franklin be so good as to peruse it, and suggest such alterations as his more enlarged view of the subject will dictate?” Ben Franklin made few suggestions, but in one of the most memorable, he changed the statement “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” to “We hold these truths to be self-evident”–a significant alteration that took the deity out of the equation, and replaced it with the authority of reason. The rest is history. Though in failing health, the old warhorse on October 27, 1776 embarked for France on one final mission–to solicit the help of France in the Revolutionary War. However, France was war-weary from its conflict with Britain that had ended 13 years earlier, so the success of the mission looked to be a long shot. Fortunately, Franklin’s reputation had preceded him to Paris. In his capacity as minister plenipotentiary, he was able to secure, in secret negotiations, a significant sum of money and 44,000 troops that helped sway the Revolutionary War in favor of the American colonies. After the war, Dr. Franklin played a key role in negotiating the Treaty of Paris that was signed on September 3, 1783, creating the United States of America as a sovereign nation. Yet, one of his most important contributions that would enshrine him in history as one of America’s Founding Fathers, was still to come.

On May 25, 1787, enough delegates to constitute a quorum convened at the Pennsylvania State House to draft the new US constitution. As Pennsylvania’s delegate from Philadelphia, Ben Franklin served as host of the Constitutional Convention that would span several months. From the beginning, the meetings were fraught with squabbles and infighting as the delegates attempted to set terms that would favor their constituents. The more populous states wanted representation by population, while states like Delaware were demanding equal representation. After more than 3 months of acrimonious debate, it was proposed that Congress would consist of a Lower House where representation would be proportional to population and an Upper House where all states would have an equal number of delegates. This compromise would seem to meet the demands of both the larger and smaller states. However, passionately held differences of opinion threatened to derail the entire process–leaving the disparate states without a government. At this watershed moment in history, Ben Franklin’s wisdom would be put to the test.

On Tuesday, September 17, 1787, Dr. Franklin rose to address the delegates who were convened to vote on a drafted constitution that seemed to please no one. The eminent host of the Convention had remained relatively quiet throughout the proceedings of the previous months, but now, at 81 years of age and double the median age of all the delegates, he was regarded as the voice of reason. Since his failing health prevented him from delivering his written speech, he passed it to James Wilson for reading:

Mr. President [addressing George Washington]

I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. Most men indeed as well as most sects in Religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them it is so far error.

I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected? It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does… I hope therefore that for our own sakes as a part of the people, and for the sake of posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution (if approved by Congress & confirmed by the Conventions) wherever our influence may extend, and turn our future thoughts & endeavors to the means of having it well administered.

And then in a move for closure, he finished with:

On the whole, Sir, I can not help expressing a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility, and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this instrument.

Of the 55 delegates, 39 signed. The final ratification of the US constitution was completed within a year.

Ben Franklin’s speech at the Continental Convention, moved the delegates from discord to harmony. He understood the persuasiveness of confessing fallibility to encourage others to acknowledge the limits of their own perceptions. As expressed in an aphorism he had written in Poor Richard’s Almanack 4 decades earlier,“ None but the well-bred man knows how to confess a fault or acknowledge himself in an error.”