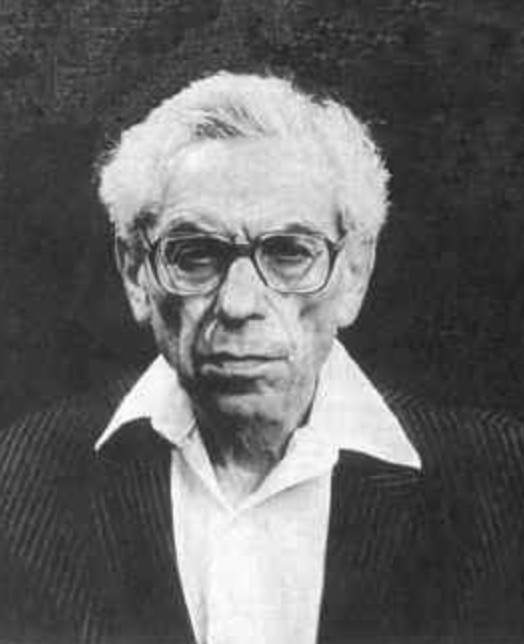

Paul Erdös, perhaps the most prolific of all mathematicians never aspired to money and survived on brief university appointments, taking stipends for presentations and visiting various friends in the mathematics community for days at a time. Mainly engaged in number theory, combinatorics and graph theory, he was constantly formulating mathematical problems for which he posted rewards as large as $100 to anyone who could find a solution.

At the International Conference on Mathematics in Budapest in 1988, he said, “I used to write checks for those who could solve my posted problems, and it cost me nothing because the problem solver pasted the check on his office wall to brag about his achievement. But after the invention of the photocopy machine, people pasted a copy on the wall and cashed the check. For me, it created a financial hardship.” (For insight into Erdös, visit: My Brain is Open: The Mathematical Journeys of Paul Erd…

Nikola Tesla, polymath inventor, whose intelligence spanned many different areas, became independently wealthy on royalties from his many patents, including his design of machines to harness alternating current. Passionate about his inventions, he poured substantial sums into funding new patents and marketing new products. A life-long bachelor, Tesla lived in hotels in New York City, originally at the Waldorf Astoria where he accumulated large bills. When he ran out of money, he moved to the St. Regis Hotel, and subsequently a series of different hotels, moving when his credit ran out.

Every day, Tesla walked to Central Park where he fed the pigeons. One particular pigeon that befriended him daily became his “pet” project. When the pigeon appeared at his hotel window with a broken wing and leg, he invented a device to support it during the healing process. In total, he spent over $2000 to rehabilitate it. Eventually unpaid bills caught up with him and he was evicted from the St. Regis Hotel. By the time Tesla died at age 86 in the Hotel New Yorker, he was penniless.

John Conway, the charismatic and eccentric mathematician who came from the University of Cambridge to Princeton is known to mathematicians for his discovery of what are called “Conway groups” and to the general public for his invention of the Game of Life. His biographer, Siobhan Roberts, in her book Genius at Play, writes:

Conway, not infrequently offered payment–payment he could ill afford–for treasures [solutions to math problems] outside his grasp, and likely beyond most everyone’s grasp, he assumed, meaning it was unlikely he’d ever have to pay up.

During one of his lectures, Conway posed a compound problem containing a difficult part and a very difficult part. Attempting to generate excitement, he promised to pay $100 for the solution to the difficult problem and 10 times that amount for a solution to the very difficult part. Two weeks later, mathematician Colin Mallows solved the very difficult part and claimed a prize of $10,000. Conway asserted that he had only promised a prize of $1000, but when the transcript of the lecture was reviewed, it was clear that Conway had actually said, “$100 for the difficult problem and $10,000 for the very difficult problem.” Acknowledging his mistake, Conway sent the check for $10,000 with a note reading, “Dear Colin: Well, here you are. It seems I made a fool of myself (or was I already one?) Enjoy it and don’t boast too much.”

Many people who are highly intelligent are so engaged in an academic or artistic interest that money has little value to them and they seldom focus enough on money issues to manage their financial affairs prudently.