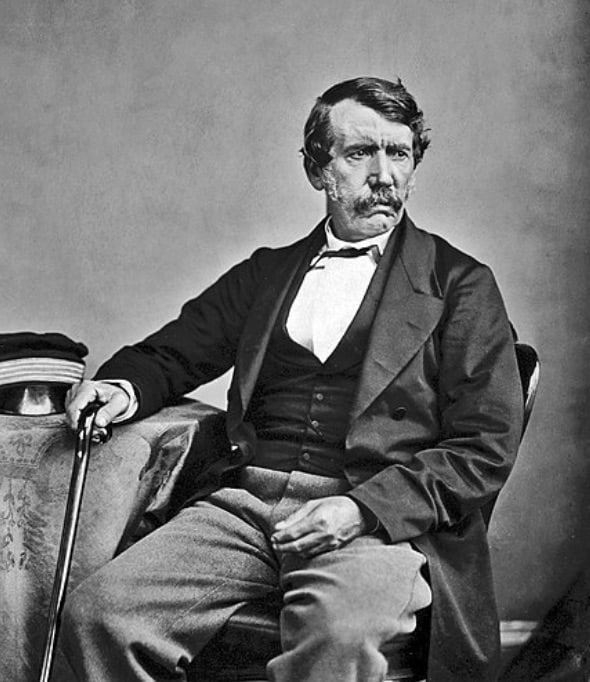

David Livingstone was born March 19, 1813, in Blantyre, Scotland. He and his 6 siblings lived with their parents in a single room of a tenement that housed the workers in a cotton factory. From age 10, he worked 14-hour days in the cotton mill, enabling him to contribute to the family coffers and also purchase a book on Latin grammar. His family were Calvanists, a religion that promoted a strong work ethic, thrift and a somewhat ascetic lifestyle. By the time David reached adulthood, he had joined an even more stringent Christian congregation that introduced him to the self deprivation and personal discipline that would serve him well in his future.

Although David’s father wanted him to focus on theology, David wished to include the study of science as a portion of his learning. At age 21, he saw a pamphlet calling for missionaries in China. Since one of the requirements of a missionary was medical training, David had to negotiate with the owners of the cotton mill to work from Easter to October at the mill, enabling him obtain his freedom to attend the Anderson’s University in Glasgow during the winter. In 1836, he entered that university, focussing on medicine and chemistry as well as theology, and on November 16, 1840, David Livingstone became a licenced physician.

A watershed moment in his life occurred when he attended a speech by abolitionist Fowell Buxton, who asserted that the African slave trade could be ended if the chiefs of the African tribes were able to obtain European products through trade, rather than through the capturing and selling of slaves.

Inspired by this vision, on November 17, 1840, the day after he became a licenced physician, David Livingstone set sail for the Cape of Good Hope, reaching that destination on March 15, 1841. In the years that followed, Livingstone, now an ordained minister, traveled through jungles and mountainous areas by oxcart to various settlements in Africa, helping to build and operate missions in Central and South Africa. In 1851, Livingstone came upon the Zambezi river and it became his major highway for exploring the African interior, eventually bringing him to his discovery of the spectacular waterfall that he named, “Victoria Falls,” in honour of Queen Victoria.

In December 1856, Livingstone returned to England where he had been awarded the Patron’s Medal by the Royal Geographical Society for his explorations. However, by 1858, he was on another expedition to Africa that would be followed by yet another return to England and a third expedition to Africa in 1866 to find the source of the Nile River. Though he would never locate the source of the Nile, his travels throughout Africa enabled him to map areas of that continent that were hitherto unknown, eventually winning him a gold medal and membership as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

During this third expedition, Livingstone suffered a variety of illnesses including, pneumonia and cholera, and had no access to medication because all his supplies had been stolen. For a period of 6 years, none of his written communications had reached the outside world and David Livingstone (in spite of his name) was presumed dead. In 1869, the New York Herald newspaper sent Henry Morton Stanley to Africa to track down the famous explorer. On November 10, 1871, Stanley reached the town of Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika and gained his first glimpse of the aging icon. According to legend, he greeted him with an extended hand and the salutation “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” to which Livingstone responded, “Yes”, and then, “I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you.”

David Livingstone would never return to England, and died on May 1, 1873 at the age of 60 in the village of Chipundu, in present-day Zambia, from malaria and internal bleeding resulting from dysentery. Observing the atrocities of the slave trade in Africa, had written in his diary:

The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems really to be broken-heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves… Twenty one were unchained, as now safe; however all ran away at once; but eight with many others still in chains, died in three days after the crossing. They described their only pain in the heart, and placed the hand correctly on the spot, though many think the organ stands high up in the breast-bone.

In this, he captured a graphic example of what Winston Churchill termed as “man’s inhumanity to man.”