Many people visiting this site in recent weeks have expressed ideas about the gifted–their social eccentricities and their unique talents. Some gifted people have suggested that their high IQ has made them feel socially isolated and sometimes rendered them a victim of bullying. Among the gifted, there are many who are defeated by their early experiences and never actualize their potential, while others see their cognitive attributes as an advantage and convert them into accomplishments. Some of my research into giftedness is presented in the following excerpt from Intelligence: Where we Were, Where we Are, & Where we’re Going.

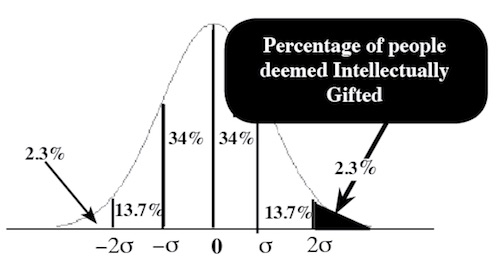

In assessing the value of the gifted to our society, we are prompted to ask what proportion of significant contributions come from that elite sector endowed with cognitive or creative talent. In psychology and education, the intellectually gifted are typically defined to be those with IQ at least two standard deviations above the mean, i.e., IQ ≥ 130. Furthermore, if accomplishment is strongly correlated to intellectual giftedness, we might expect that accomplishments in a modern industrialized society (where virtually everyone has access to education) might also be distributed in accordance with the normal distribution.

In Human Accomplishment, Charles Murray presents data to identify the sources of human achievement in the arts and sciences from the beginning of recorded history to 1950. While Murray accepts that human intelligence is distributed according to the normal distribution, he provides data to support the claim that achievement throughout the human population is represented by the Lotka rather than the normal distribution. In fact, he asserts that the overwhelming number of world-changing discoveries, inventions, and creative works come from a remarkable few whom he designates as the “giants” in those domains:

When you assemble the human résumé, only a few thousand people stand apart from the rest. Among them, the people who are indispensable to the story of human accomplishment number in the hundreds. Among those hundreds, a handful stand conspicuously above everyone else.

This “handful” of giants in each field have contributed more than all the rest. This idea has been expressed quantitatively in a variety of forms. For example, Lotka’s law asserts that the number of scholars who publish exactly n papers is approximately C/na where C is a constant specific to a given discipline and a is a constant close to 2. Heuristically speaking, this is like an inverse square law: the number of authors who have published n papers drops off as 1/n2. Such heuristically established “laws” indicate that the elite class of the “accomplishment gifted” is a relatively small subset of the intellectually gifted. Why is it that only a fraction of gifted people are making the great intellectual breakthroughs, inventions, and creative works that qualify them as the “giants” in their domain?

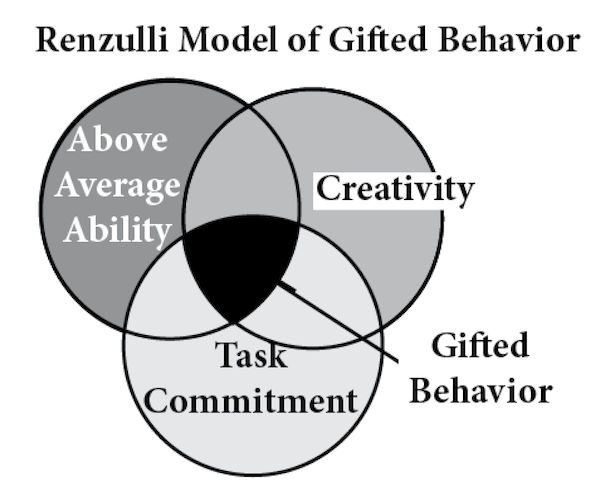

In 1978, Joseph Renzulli introduced what is known as his “three-ring” definition of giftedness. He argued that “gifted behaviors” consist of 3 components: ability, task commitment, and creativity. Gifted behavior, as the intersection of the three components flourishes when all three factors are simultaneously in play. That is, for someone to display gifted behavior, he or she must have above average ability, exceptional creativity, and extraordinary task commitment. If we assume that these three behaviors are independent and normally distributed throughout the population, then we can make a crude estimate of the percentage of people in the general population who will display gifted behavior as follows.

If we define “above average ability” to be one standard deviation above the mean, then we know from the figure above that about 16% of the population satisfies this criterion for activities that strongly correlate with IQ. Similarly, let’s also consider that about 16% of the population satisfies each of the criteria for creativity and task commitment. Our contestable assumption that these three components are independent enables us to estimate the proportion of people who may exhibit gifted behavior to be about 0.16 × 0.16 × 0.16 ≈ 0.004 or 0.4% of the population. This is substantially smaller than the 2.3% who are 2 standard deviations above the mean in intelligence or in any normally distributed characteristic. If there are more than 3 components (as suggested by Nobel laureate William Shockley) required for gifted behavior, this would skew even more, the distribution of creative achievements throughout the human population.

In Empowerment, psychologist Gene Landrum notes that the greatest athletes have exceptional physical skills, but argues that it’s their emotional and mental dispositions that catapult them from exceptional to eminent status:

The truly eminent have physical skills that locate them on the right tail of the normal curve, but emotional and mental dispositions are the factors that combine to move the eminent to the extreme right tail of a Lotka curve, way ahead of the pack.

Indeed, exceptional physicality embedded in the DNA is a necessary condition for an athlete to participate in the Olympics but, as in the case of mathematical performance, additional qualities of personality are required to win the gold. Vital to the development of those qualities is an environment in which world-class performance is valued and nurtured. A society that recognizes the importance of giftedness, especially mathematical giftedness, and celebrates intellectual achievement stands to reap substantial rewards.