IQ measures what is called the general component of human intelligence, denoted by the symbol g; it is a highly pervasive component that influences many aspects of a person’s life. To many people the items that appear on IQ tests such as the Raven’s Progressive Matrices or the Weschler tests, seem rather academic and unrelated to tasks in real-life contexts. Consequently, many regard IQ as a measure of book-learning skills–skills perceived to be irrelevant in the everyday world of work. Yet, such tests are used for the selection of job applicants in business, and industry and for recruitment in the military. Why?

In her article Why g Matters, (See Intelligence Vol. 24 Issue 1. 1997. pp. 79–132) psychologist Linda Gottfredson observes:

Research in job analysis and personnel selection refutes the claim that g [measured as IQ] is useful only in academic pursuits. Intelligence turns out to be more important in predicting job performance than even personnel psychologists thought just two decades ago…The key observation here is that personnel psychologists no longer dispute the conclusion that g [IQ] helps to predict performance in most if not all jobs.

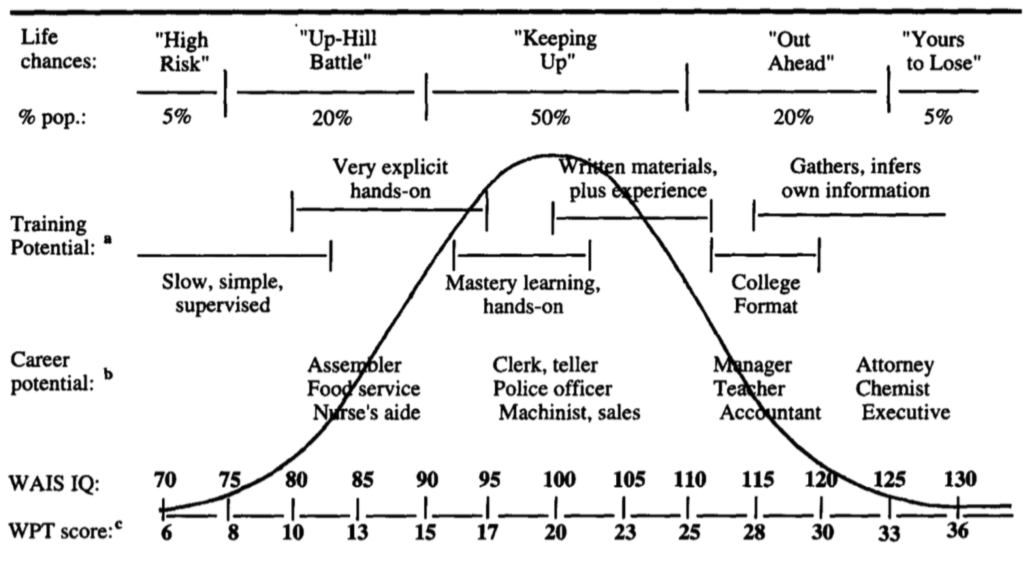

In supporting her assertion of a close connection between IQ and job performance, Gottfredson compiled information from the Wonderlic Personnel Test and Scholastic Level Exam to create the display included below.

The row labeled training potential reveals that those of IQ below 80 usually need constant supervision and should be assigned cognitively simple tasks. Those of higher IQ, but less than 105, can typically learn more complex tasks, but the training methods should involve mastery learning, i.e., frequent practice and reinforcement until the job is performed routinely. Those of IQ higher than 110 can be expected to learn independently from books and manuals and do not usually need much formal instruction.

The row labeled career potential shows the spectrum of employment ranging from routine, relatively unskilled occupations at the low IQ levels to the occupations demanding complex cognitive skills at the high IQ levels. As we move from left to right along this employment spectrum, we see that the level of job complexity increases along with the corresponding IQ scores. It is not surprising that the increasing levels of complexity in the jobs match the increasing levels of complexity in the items on the IQ tests.

Of course, the graph represents average IQs in various occupations that have exceptions at the individual level. That is, there are those individuals of average or lower IQ who find employment in teaching, law, and medicine, just as there are individuals of high IQ who languish in unskilled occupations. However, the measure of IQ is an excellent predictor of career potential, as opposed to career attainment. The graph represents averages and a low IQ should not be interpreted as a barrier to achievement. When we observe superachievers in life, we find that non-cognitive attributes, such as tenacity and passion, are often major factors in their success. As Gottfredson observes:

The causal impact of g does not mean, of course, that it is the only cause of differences in job performance. Other personal and environmental attributes clearly matter. However, the evidence is overwhelming that differences in intelligence are a major source of enduring, consequential differences in job performance.

There is also some evidence that IQ can be enhanced by appropriate intellectual stimulation. As one of my favourite math teachers once said, “You have only as many brains as you use.” We are all much more capable than we think.