In August 1900, a 21-year-old student named Albert Einstein graduated in physics from Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) in Zurich with a commendable mark of 4.91 out of 6. Since it was customary for students to be offered junior academic appointments upon graduation, Einstein was bitterly disappointed when he was the only one of his graduating friends who was passed over. His independence of thought and his unwillingness to submit to intellectual authority had been perceived as arrogance by his elders, preventing him from winning an academic post.With no means of supporting himself, he desperately sought employment.

On June 16, 1902, after two years of temporary tutoring and teaching jobs, Einstein finally landed a job as an engineer Class III in the Swiss Patent Office in Berne. This “shoemaker’s job”, as he later described it, engaged him in assessing the viability of inventions submitted for patents. In a letter to his friend Conrad Habicht, he wrote, “[This job gives me] besides eight hours of work…eight hours of idleness plus a whole Sunday.” The “idleness” provided by this “shoemaker’s job” would give Einstein the freedom to explore the foundations of physics and reconstruct Newton’s model of the universe.

In 1905, while still toiling as a clerk in the Patent Office, Einstein was awarded a doctorate by the Zurich Physics Institute for his 21-page dissertation, A New Definition of Molecular Dimensions. Though the examining committee had been divided on whether it was “physics” or “mathematics”, a final judgment asserted, “[despite] crudeness in style and slips of the pen in the formulas which can and must be overlooked, …, [the paper displays a] thorough mastery of mathematical methods.”20

Achieving a Ph.D. in physics was a relatively minor accomplishment for Einstein in a year that has become known as his annus mirabilis (miracle year). On March 17, 1905, just three days after he turned 26, Einstein submitted to the physics journal Annalen der Physik a paper explaining the photoelectric effect–a paper for which he would eventually receive a Nobel Prize.

Then, on May 11, just two months later, he submitted to that same journal another opus magnum, this time on Brownian motion, explaining how colliding molecules produce the random motion observed when microscopic particles like pollen grains oscillate in water.

Despite the significance of these two papers, they would eventually be eclipsed in importance by a third containing a revolutionary insight captured in his Special Theory of Relativity–an insight that would revolutionize physics irrevocably by challenging Newton’s assumption that space and time are absolute. These three papers, any one of which would have earned Einstein a place among the greatest physicists of all time, appeared in the celebrated Volume 17 of Annalen der Physik in July 1905.

As if this flurry of papers were not enough, on September 27 of the same year, he submitted yet a fourth paper, an “addendum” to his Special Theory of Relativity which was subsequently published in Volume 18. In it, he derived his famous equation E = mc2 that defines his mass-energy equivalence principle and often serves as an icon for the discoverer himself. His counterintuitive assumption that time is not absolute was met with the same skepticism that Galileo and others had faced when promoting ideas that were perceived to be outrageously radical.

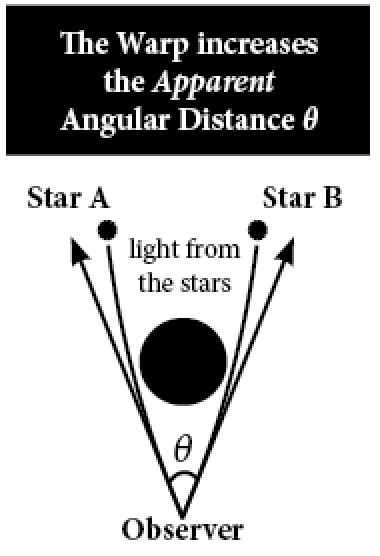

Undaunted by the resistance to his ideas, Einstein in 1907 at age 28, embarked on a journey far more ambitious than his Special Theory. In what has become known as his General Theory of Relativity, he challenged Newton’s assumption that gravity is a force propagated through a flat Euclidean space, and instead proposed that space is “curved” by the presence of mass. Furthermore, he asserted that this “warp” defines the paths that objects follow as they move through a complex interweaving of space and time, called “spacetime.” It would take him another 10 years to flesh out his original insights, but with help from mathematicians, Grossmann, Minkowski, and Schwarzchild, he was able to express this theory in a coherent set of equations with a predictive power that could be tested. For if indeed, space is warped around large masses such as the sun, we would expect that beams of light from stars would bend as they pass near the sun en route to the earth. Einstein challenged astronomers to make observations that would confirm or contradict his prediction.

The opportunity to test his theory would come in 1919 when a total solar eclipse would block the sun, making the stars visible during the day. The angular distance between two stars measured during the eclipse, when the sun is flanked by the stars, would be compared with their angular distance at night. Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity predicted that the angular distance measured during the eclipse, would be greater than the nighttime angular measure by 1.7 seconds of arc (approximately 0.0005 degrees).

In late April, an expedition, headed by astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington, journeyed to Principe Island off the coast of West Africa, where a full eclipse would be visible. May 29, 1919 arrived, along with heavy rains in the morning that threatened to obscure the eclipse during all or part of the five-minute window when it would occur. However, in the early afternoon, the sky began to clear and by 3:13 p.m. the heavens had opened enough to reveal the sun and some stars. In a frenzied five-minutes, Eddington changed plates on his camera sixteen times before the eclipse ran its course and the sun emerged from behind the moon to erase all the stars. These sixteen photographs were closely-guarded treasures that would validate or disprove Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity.

Finally, on November 6, after months of scrutiny, the results of Eddington’s expedition were presented at a joint meeting of members of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. With all the pomp and circumstance of formal British society, Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Dyson announced, “After a careful study of the plates, I am prepared to say that there can be no doubt that they confirm Einstein’s prediction.” J. J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron, asserted, “The result is one of the greatest achievements of human thought.”

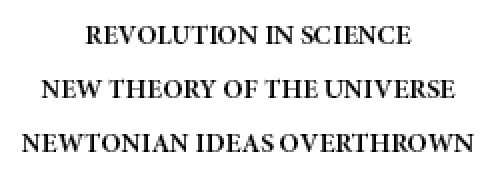

The day following Dyson’s announcement, The Times of London front-page headline blazoned:

News of Eddington’s verification of Einstein’s Theory spread like a tsunami from Europe across the Atlantic, reaching the front page of The New York Times on November 10, 1919. A world, weary from the horrors of World War I, welcomed a new era of scientific inquiry and international cooperation. In the days that followed, the tsunami continued across middle America to California, carrying with it the name “Albert Einstein.” Science and technology that had been dedicated to the development of weapons was now elevated to the loftier goal of universal enlightenment. Einstein became its champion and an overnight celebrity.

The media elevated Einstein to demigod status, emphasizing the abstruse equations and asserting that only a dozen scientists could comprehend the complicated theory. Einstein himself, with his disheveled appearance, his contemplative pipe, and his unworldly ways became the caricature of genius.

In 1921, Einstein made his first trip to America. A swarm of newspaper reporters greeted him as his ship pulled into the New York harbor and before he could disembark, Einstein found himself embroiled in a press conference. Through an interpreter, he answered the questions with a wit and twinkle, suggesting that he was enjoying the attention.

During his speaking tour in America, Einstein packed the Metropolitan Opera House in New York to the rafters, visited Washington D.C. where he met with President Warren G. Harding, and gave lectures in Chicago to overflow crowds. The halo of awe that bordered on reverence accompanied Einstein wherever he went and people flocked to get a glimpse of this eccentric, self-effacing genius. More than 15,000 people attended parades in his honor in Hartford, Connecticut and Cleveland, Ohio.

On his second visit to America, Albert and his wife Elsa were invited to the black-tie premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s famous film City Lights. As Chaplin and Einstein entered the theater to thunderous applause, Chaplin observed, “They cheer me because they all understand me, and they cheer you because no one understands you.”

Through an unprecedented demonstration of the power of abstraction, the eccentric, disheveled, unworldly scientist, who saw the universe through the lens of abstruse mathematics embedded in four-dimensions, became the ultimate icon for genius. [This tribute is an excerpt from the book Intelligence, IQ & Perception published in 2022 See https://amzn.to/3N5FrOU