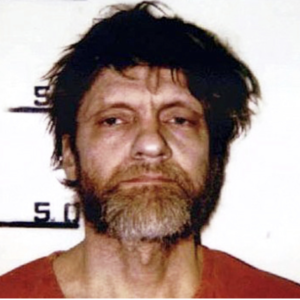

On December 14, 2021, Ted Kaczynski a.k.a., the Unabomber, was transferred from his cell in a maximum security federal prison in Colorado to the U.S. Bureau of Prison’s FMC Butner medical center in North Carolina after serving almost a quarter century behind bars. After pleading guilty to planting home-made bombs that killed three people and injured 23 others in various parts of the country between 1978 and 1995, he was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

For nearly two decades the American public was terrorized by sporadic appearances of devastating bombs on airplanes, biology labs, and mailboxes that brought injury or death to what seemed to be randomly selected victims. In the cat-and-mouse contest between the perpetrator, described as an “evil genius,” and the FBI, the evil genius prevailed, leaving no clues and rendering the police helpless–in spite of a posted $1,000,000 reward and a 1-800 hotline. When it appeared that this “madman” would elude capture forever, a strange thing happened.

In late 1995, several media outlets received a proposition from the Unabomber indicating that he would “desist from terrorism” if a major newspaper would publish, unabridged, his 35,000-word essay titled Industrial Society and its Future. On September 19, 1995, hoping that its publication would reveal his identity The New York Times and The Washington Post published the essay.

After the publication of the Unabomber’s manifesto, the hot line received over a thousand calls a day but there was little or no information that would reveal his identity. Meanwhile, David Kaczynski shared letters received from his brother. Their similarity in writing style to the manifesto, enabled the FBI to obtain a search warrant of his brother’s cabin. On April 3, 1996, FBI agents visited Ted Kaczynski’s cabin where they found a live bomb that was ready for mailing, along with a collection of bomb materials. The Unabomber was arrested and subsequently indicted. On January 22, 1998, Ted Kaczynski pled guilty to all charges– a plea that saved him from the death penalty.

What was the Premise of the Kaczynski Manifesto?

The introduction of Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future, begins with his assertion that industrial society and personal autonomy are incompatible:

The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in “advanced” countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering … and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation.

… For purely technical reasons it is not possible for most individuals or small groups to have much autonomy in industrial society. Even the small-business owner commonly has only limited autonomy. Apart from the necessity of government regulation, he is restricted by the fact that he must fit into the economic system and conform to its requirements.

How Does Kaczynski Support his Argument?

The manifesto argues that humans evolved to live in tribes, including family units and small villages, pursuing the natural survival goals. By providing for these basic needs, technology forces humans to create “surrogate goals” that are not intrinsically satisfying because they are not vital to survival. The result, he claims, is manifest in widespread feelings of personal unfulfillment, detachment and social unrest. He asserts:

The system HAS TO force people to behave in ways that are increasingly remote from the natural pattern of human behavior. For example, the system needs scientists, mathematicians and engineers. It can’t function without them. So heavy pressure is put on children to excel in these fields. It isn’t natural for an adolescent human being to spend the bulk of his time sitting at a desk absorbed in study. A normal adolescent wants to spend his time in active contact with the real world. Among primitive peoples the things that children are trained to do tend to be in reasonable harmony with natural human impulses. Among the American Indians, for example, boys were trained in active outdoor pursuits just the sort of thing that boys like. But in our society children are pushed into studying technical subjects, which most do grudgingly.

In that passage, Kaczynski is arguing that the cognitive processes, that Kahneman later characterized as System 1 thinking (i.e., visceral, instinctive thought) are natural to us and that artificially prolonged involvement in System 2 thinking (i.e., deductive thought) is unnatural and less satisfying.

A Manifestation of Madness?

Several people have attempted to determine whether Kaczynski was a rational “evil genius,” or whether he was suffering from a mental disorder. Psychiatrist, Dr. Sally Johnson, diagnosed him prior to his trial as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and a paranoid personality disorder.In part, it was argued that he must be insane to have committed such heinous crimes–a legal version of the Catch-22 dilemma. Psychiatrist Dr. Park Dietz suggested Kaczynski was not psychotic, but was afflicted with a schizotypal personality disorder. The two disorders are similar, usually manifesting in hallucinations, delusions, and sometimes disorganized articulation and social detachment. However, Kaczynski claimed in his book Technological Slavery, published in 2010, that two prison psychiatrists, who attended to him often, disagreed with that diagnosis.

How Valid are Kaczynski’s Concerns about Technology?

Concerns about the long-term effects of a mechanized society on personal autonomy have been expressed by many scientists and writers since the First Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. Lamenting the mass exodus of farm workers from the villages and towns into the factories of the industrialized cities, Oliver Goldsmith wrote in 1770, his poem The Deserted Village containing this oft-quoted excerpt:

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay:

By the early 19th century, machines were taking over the textile industry, replacing the craftsmen and artisans who could not compete with the productivity of the new technology. Opposition to the automation of their industry emerged in 1811 from a secret organization of English textile workers who feared the machines would destroy their livelihood. Called “Luddites” after their fictional leader Ned Ludd, they waged war on industrialization by destroying the new machines and sometimes entire factories. The Luddite movement that ran from 1811 to 1816 was crushed when the British army captured and hanged the leaders. Since that time, the term Luddite is applied to describe those who oppose new technologies.

As increasingly more sophisticated technologies emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries, many voiced the concern that these new innovations were changing irrevocably the nature of our lives and even threatening our existence. On February 16, 1931 Albert Einstein, addressing students at the California Institute of Technology, warned of the dangers of applied science:

Just consider a quite uncivilized Indian, whether his experience is less rich and happy than that of the average civilized man. I hardly think so. There lies a deep meaning in the fact that the children of all civilized countries are so fond of playing “Indians”.

Why does this magnificent applied science which saves work and makes life easier bring us so little happiness? The simple answer runs: because we have not yet learned to make sensible use of it. In war it serves that we may poison and mutilate each other. In peace it has made our lives hurried and uncertain … Concern for the man himself and his fate must always form the chief interest of all technical endeavours … in order that the creations of our mind shall be a blessing and not a curse to mankind. Never forget this in the midst of your diagrams and equations.

In his seminal book The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society, published in 1950,MIT mathematician and visionary Norbert Wiener warned of the dangers of unfettered technology:

The new industrial revolution is a two-edged sword… It may be used for the benefit of humanity, but only if humanity survives long enough to enter a period in which such a benefit is possible. It may also be used to destroy humanity, and if it is not used intelligently it can go very far in that direction.

Acknowledging that the Manifesto’s concerns about technology are shared by many mainstream scientists, Alston Chase, Professor Emeritus at Macalester College in Minnesota asserted:

But the truly disturbing aspect of Kaczynski and his ideas is not that they are so foreign but that they are so familiar. The manifesto is the work of neither a genius nor a maniac. Except for its call to violence, the ideas it expresses are perfectly ordinary and unoriginal, shared by many Americans. Its pessimism over the direction of civilization and its rejection of the modern world are shared especially with the country’s most highly educated.

What separated Kaczynski from those who shared his concern about technology was his intention to use violence to address the perceived problem. Could this be the line that divides sanity from insanity? Even the psychiatrists disagree psychologists cannot establish a precise demarcation. It may be that we’re each located somewhere on a continuum between the vague concepts of “sane” and “insane.”

This post is a snippet from Intelligence, IQ & Perception, published in 2022 https://www.intelligence-and-iq.com/intelligence-iq-perception/