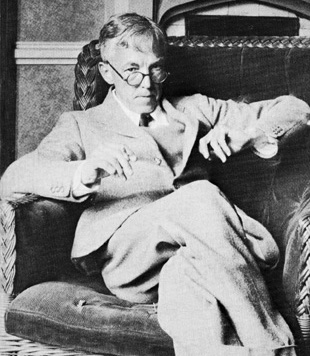

Godfrey Harold Hardy was born on February 7, 1877 in Surrey, England. Some described him as a child prodigy who at the age of 2 years was able to write numbers up to millions. When in church, he entertained himself by factoring the hymn numbers. In 1896, at age 19, he enrolled at Cambridge University and with only two years of preparation, stood fourth in the prestigious Tripos examination. As he progressed through the ranks of academe, his intellectual prowess in analytic number theory established him as one of the top mathematicians in Europe.

Hardy’s 35-year collaboration with the British mathematician J. E. Littlewood that began in 1911, yielded publications on the Riemann zeta function, inequalities, and the theory of functions, as well as a series of papers Partitio numerorum that employed the Hardy-Littlewood-Ramanujan analytical method. The textbook on Number Theory that Hardy co-authored with E. M. Wright became a classic that was used by several generations of students.

One morning in 1913, Hardy, received a large untidy envelope adorned with Indian stamps. and containing within, pages of rough notes displaying weird and unfamiliar looking mathematical theorems and identities–products of the intuition of a brilliant but unschooled mind. The originator of the letter was a poor 26-year-old clerk from Madras, India, named Srinivasa Ramanujan. So impressive was the manuscript, that Hardy made provision for Ramanujan to visit Cambridge to collaborate with him in mathematical research. In the seven years that followed, Ramanujan and Hardy established one of the most successful collaborations in the history of mathematics. In a tragic turn of events, Ramanujan contracted tuberculosis at age 32, while at the peak of his creativity. Visiting him on his death bed, Hardy opened with trivial conversation. “I drove over here to-day in a taxi with a boring number, 1729.” Ramanujan’s face brightened as though he had met an old friend, “Oh no, that’s not a boring number; it’s the smallest number that’s representable as a sum of two cubes in two different ways!” Hardy, himself a gifted intellect, regarded his discovery of Ramanujan as one of his greatest achievements. Hardy died on December 1, 1947 at age 70.

As Hardy came near the end of his productive years, he wrote a little philosophical book titled A Mathematician’s Apology, explaining that he enjoyed dedicating his life to number theory, because he was “good at it”, but acknowledged that it was a totally useless subject without applications. (He did not foresee its significant applications in cryptography, that came after his death.) Always an independent thinker, he once observed, “It is not worth an intelligent man’s time to be in the majority. There are already enough people to do that.”