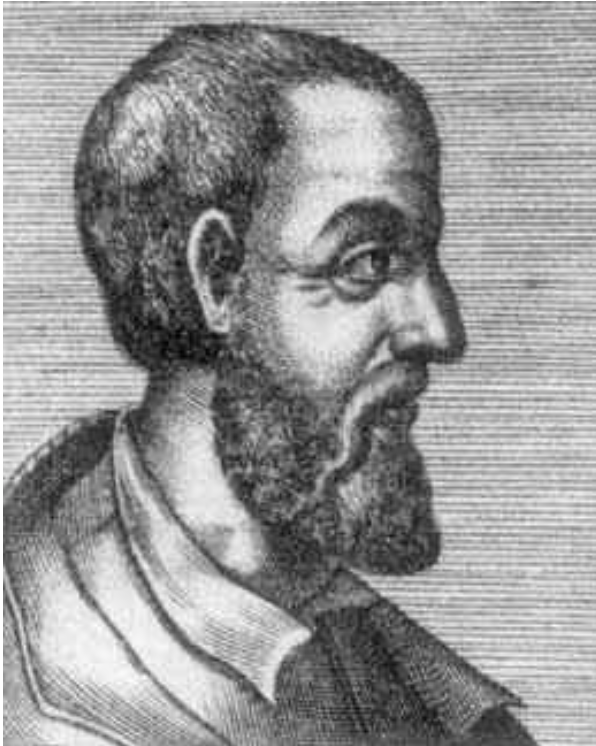

Girolamo Cardano was born on September 24, 1501 in Milan, Italy. He was the illegitimate son of Fazio Cardano, a prominent lawyer who also lectured in geometry at the University of Pavia. Girolamo learned mathematics at his father’s knee and by the time he reached university age, was recognized as an exceptional student. Although his father had wanted him to study law, the irascible youth pursued a career in medicine. In 1525, Girolamo was awarded his doctorate in medicine and applied for admission to the College of Physicians in Milan, but in spite of his outstanding scholastic record, his application was denied. Part and parcel of his intellectual gifts was an insistence on stating what he perceived as truth, whether or not it offended others. Recognizing this tendency and the antagonism it generated, he once reflected:

This I recognize as unique and outstanding amongst my faults – the habit, which I persist in, of preferring to say above all things what I know to be displeasing to the ears of my hearers. I am aware of this, yet I keep it up wilfully, in no way ignorant of how many enemies it makes for me.

Shortly after his father’s death, Girolamo became Rector of the University of Padua. Denied access to the College of Physicians, he supplemented his income by gambling, to the extent that it became an addiction. Chess, dice and especially cards absorbed increasing amounts of his time. Yet this addiction was the spark that would generate the study of probability in the years that followed. In 1539, he began writing a gambler’s manual reporting patterns in the outcomes associated with the toss of a die that eventually evolved in 1563into his formal publication Liber de Ludo Aleae (The laws of chance). This work would lie dormant for almost a century, until the 1650’s when gambling involving large sums of money became fashionable in French society. When the Chevalier de Méré, an ardent gambler, invited Blaise Pascale to resolve the now-famous problem of points, Pascale and Fermat built on the work of Cardan to lay the foundations of probability theory.

In the same year that Cardan published his work on probabilities, he became involved in the quest to find a formula for roots of a cubic equation. In a controversial incident with Tartaglia, who had discovered this formula, Cardano published in 1545 his famous opus, Ars Magna in which he presented formulas for the roots of cubic and quartic equations.

Cardano’s brilliance and his proclivity for generating antipathy brought him fame, recognition and trouble throughout his later years, but his wish to have his name recorded in history was ultimately achieved.