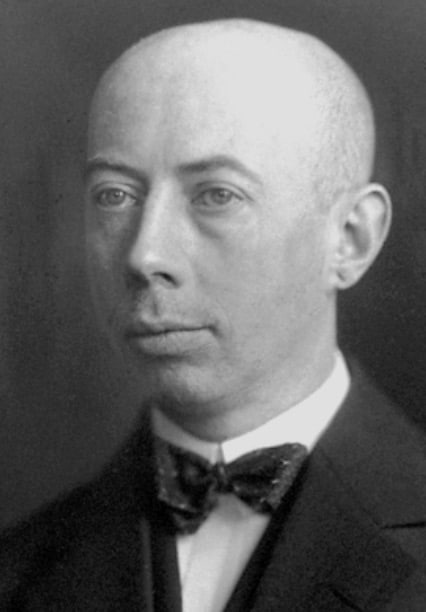

Gustav Hertz was born on July 22, 1887, in Hamburg, Germany, He was born into a family of musicians; his father a renowned musician and his mother a celebrated vocalist. He attended the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums before studying at the Georg-August University of Gottingen, the Ludwig Maximillian University of Munich, and the Humboldt University of Berlin, receiving his doctorate in 1911.

From 1911 to 1914, Hertz was an assistant to Rubens at the University of Berlin. It was during this time that Hertz and James Franck performed experiments on inelastic electron collisions in gases, known as the Franck-Hertz experiments. Together the two physicists conducted groundbreaking research on the interaction of electrons with atoms and molecules, for which they received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1925.

In 1914, World War I broke out and Hertz joined the German military and within a year, became a part of Fritz Haber’s unit that introduced poisonous chlorine gas as a weapon against the Allied troops. When seriously wounded in 1915, he returned to the University of Berlin as a Privatdozent and In 1920, took a job as a research physicist at the Philips Incandescent Lamp Factory in Eindhoven,–a position he held until 1925 when he was appointed ordinarius professor and director of the Physics Institute at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg. Three years later, he became ordinarius professor of experimental physics and director of the Physics Institute at the Technical University of Berlin.

With the rise of Nazism during the 1930’s, Gustav Hertz’s Jewish background led to his classification as “second degree part-Jew, and in 1934, he was forced to resign his professorship at the Technical University of Berlin. The Siemens Company appointed him director of a research laboratory where he was able to continue his research in atomic physics, ultrasound and isotope separation up to and during World War II, as Germany sought a nuclear bomb.

In early 1945, Hertz and three colleagues, Manfred von Ardenne, Max Volmer and Peter Thiessen, fearing for their futures, formed a pact that they would seek sanctuary in the Soviet Union and work for the Soviet war effort provided they were not prosecuted for any of their past political activities, and that they would be able to continue their work with minimal interruption. On April 27, 1945, as the Soviet army moved into Germany, the four scientists were picked up in an armoured car and transported to the Soviet Union where they worked on a variety of different projects including the enrichment of uranium for the production of an atomic bomb. By the end of the 1940’s there were about 300 German scientists working on Soviet weaponry. A dozen years later, when the Soviet Union startled the world with the launch of Sputnik, American comedian Bob Hope would quip:

A lot of people think that the reason the Soviets beat us into outer space is that the Soviets have a better education system than ours. But that’s not true, it’s just that the Soviets got better German scientists after the War than we did.

In 1950, Hertz moved to Moscow from the Soviet laboratory in Aqwa, and in the next year was awarded the Stalin Prize, second class. He remained in Moscow until his appointment in 1955 to ordinarius professor at the University of Leipzig in the German Democratic Republic. Gustav Hertz died on October 30, 1975 in East Berlin at 88 years of age. He is best known for his contributions to the field of physics, particularly his work on the verification of the quantization of energy levels in atoms, which was crucial in the development of Bohr’s model of the atom in quantum mechanics.