Yes, there are several known, and probably many more unknown cases in which a student has done poorly or failed tests and gone on to achieve greatness. I will provide three examples: one who failed in elementary school, and two who failed at higher levels.

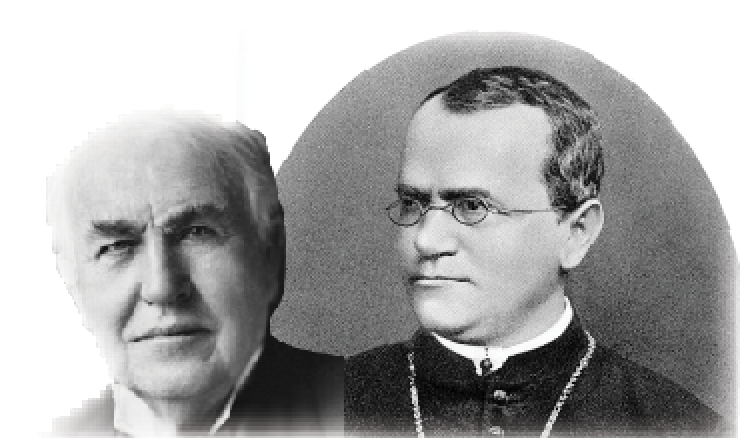

On February 11, 1847, Thomas Alva Edison was born in Milan Ohio, the seventh and last child of Samuel Edison Jr. and Nancy Elliot. When Thomas was 7 years old, the family moved to Port Huron, Michigan. By this time he had been in and out of several different schools in Ohio and Michigan on account of a reading disability that we know today as dyslexia. A few months into his first-grade school year, his teacher Reverend G. B. Engle, became frustrated by Edison’s learning difficulties and called him “addled.” The scorned youngster stormed out of school ending his formal education. Fortunately his mother was a teacher, so Thomas was home-schooled thereafter.

Under his mother’s tutelage, Edison became an avid reader, pursuing his natural curiosity through books and chemical experiments. By age 13, he was earning $50 per week selling candy, fruit, and newspapers on the Grand Trunk Railroad run from Port Huron to Detroit. His flair for entrepreneurial enterprise was further evident at age 15 when he wrote and printed, on a small printing press located in a baggage car, The Grand Trunk Herald–a newspaper that he sold to the 400 railroad employees. Using money earned from his enterprise, he purchased books on chemistry along with chemicals for experiments that he conducted in his own makeshift baggage car “lab.” Years later Edison said that both he and his laboratory were tossed off the train at Smiths Creek, Michigan by an angry train conductor when a chemical experiment went horribly wrong and burst into flame.

Unrelenting in his exploration of chemistry and electricity, he filed in 1869, at the age of 22, his first patent–an electric vote recorder. By the time he had reached the age of 29 in 1876, Edison had built a facility in Menlo Park, New Jersey, that would eventually become the first industrial research laboratory in the United States. While working relentlessly to perfect the recently-invented telephone, Edison became obsessed with the idea of recording the human voice. Within a year, he developed a primitive phonograph, recording his rendition of the nursery rhyme “Mary had a little lamb.” Although he was deaf in one ear and partially deaf in the other–a consequence of scarlet fever in his early childhood–he would bite into a wooden part of his new phonograph, so that the vibrations would reach the auditory nerve and enable him to hear.

News of his invention spread rapidly throughout the world, bringing him international fame and flocks of visitors, who traveled from afar, to witness a burgeoning new era in electronic devices. Less than two years later, Edison discovered the invention for which he is most remembered–the first commercially viable incandescent light bulb. The first air conditioning system, the motion picture camera, and a host of other life-enhancing innovations followed soon after and Thomas Edison, as the personification of inventive genius, became immortalized as the “Wizard of Menlo Park.”

In 1850, Father Gregor Mendel failed his teacher certification examinations. His lowest mark was in biology. Though uncertified, he was permitted to teach natural science as a substitute teacher at the technical high school in Brno, (in the modern-day Czech Republic). To secure a regular teaching position, he would need to retry the teacher certification examination. To this purpose, in 1853, he immersed himself in the study of the natural sciences at the University of Vienna. When Mendel presented himself in 1856 for the three-day examination, he was study-weary and suffering examination anxiety. On the day of the oral examination, he became embroiled in an acrimonious disagreement with the biology examiner. This unfortunate incident resulted in a second and permanent failure to secure his teaching certificate. As in Darwin’s case (Darwin failed to qualify for the tripos examination at Cambridge), Mendel’s failure to pass an examination was a watershed event that would change the direction of his life and lead to a scientific breakthrough of epoch-making proportion.

Dejected by his failure, at the age of 34, Mendel returned to his substitute teaching job at St. Thomas’s Abbey in Brno, and the central passion of his life–gardening. Father Mendel was fascinated by the mechanism of heredity that passes the traits of a parent to its offspring–the very question that would confound Darwin a decade later. Searching for strains of pea plants that would breed “true”, i.e., produce offspring with traits identical to the parent, he cross-pollinated various varieties of pea plants in the monastery greenhouse.

Mendel reported the results of these experiments in 1865 to the Natural Science Society at Brno in a paper titled, Experiments in Plant Hybridization. One of his observations was that “hybrids [when “mated”] form seeds having one or the other of two differentiating characteristics.” Though this hypothesis would ultimately lay the foundations for the modern theory of genetics, his paper was received with modest enthusiasm by a gathering of about 40 people. Apparently, the arcane nature of Mendel’s graphs, charts, and tables mystified his audience who failed to realize that he had discovered the indivisible “elements in the periodic table of hereditary traits.” (This was four years before Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev published his periodic table of chemical elements.) Gregor Mendel is now celebrated as the father of genetics.

A third dramatic example is the story of Évariste Galois. His name is unknown to most people because his contribution came in a relatively arcane field of mathematics known as group theory. However, you can read a brief bio on the link provided above, or read a comprehensive biography in Whom the Gods Love, by Leopold Infeld.