It took a long time for Einstein’s ideas to gain acceptance. His first paper on his Special Theory of Relativity was published in 1905, when he was 26 years old. It was the same year he received his Ph.D. Einstein’s assertion that time was not absolute ran against Newton’s assumption that had stood for more than two centuries and his theory was considered outrageously radical by the scientific community. Experimental physics was not sufficiently equipped to test his theory.

Undaunted by the resistance to his ideas, Einstein in 1907 at age 28, embarked on a journey far more ambitious than his Special Theory. In what has become known as his General Theory of Relativity, he challenged Newton’s assumption that gravity is a force propagated through a flat Euclidean space, and instead proposed that space is “curved” by the presence of mass. Furthermore, he asserted that this “warp” defines the paths that objects follow as they move through a complex interweaving of space and time, called “spacetime.” It would take him another 10 years to flesh out his original insights, but with help from mathematicians, Grossmann, Minkowski, and Schwarzchild, he was able to express this theory in a coherent set of equations with a predictive power that could be tested. For if indeed, space is warped around large masses such as the sun, we would expect that beams of light from stars would bend as they pass near the sun en route to the earth. Einstein challenged astronomers to make observations that would confirm or contradict his prediction.

During all this time, some scientists were beginning to consider that Einstein’s theories might be correct, although most were skeptical. (It wasn’t until 1921 that Einstein received the Nobel Prize, but it was for his discovery of the equation E = hv that describes the energy released in the photoelectric effect. He never received a Nobel Prize for his Theory of Relativity.) The public was generally unaware of any of Einstein’s theories.

The opportunity to test his theory would come in 1919 when a total solar eclipse would block the sun, making the stars visible during the day. The angular distance between two stars measured during the eclipse, when the sun is flanked by the stars, would be compared with their angular distance at night. Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity predicted that the angular distance measured during the eclipse, would be greater than the nighttime angular measure by 1.7 seconds of arc (approximately 0.0005 degrees).

In late April, an expedition, headed by astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington, journeyed to Principe Island off the coast of West Africa, where a full eclipse would be visible. May 29, 1919 arrived, along with heavy rains in the morning that threatened to obscure the eclipse during all or part of the five-minute window when it would occur. In a frenzied five-minutes, Eddington changed plates on his camera sixteen times before the eclipse ran its course and the sun emerged from behind the moon to erase all the stars. These sixteen photographs were closely-guarded treasures that would validate or disprove Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity.

Finally, on November 6, after months of scrutiny, the results of Eddington’s expedition were presented at a joint meeting of members of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. With all the pomp and circumstance of formal British society, Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Dyson announced, “After a careful study of the plates, I am prepared to say that there can be no doubt that they confirm Einstein’s prediction.” J. J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron, asserted, “The result is one of the greatest achievements of human thought.”

The day following Dyson’s announcement, The Times of London front-page headline blazoned: Revolution in Science–New Theory of the Universe–Newtonian Ideas Overthrown

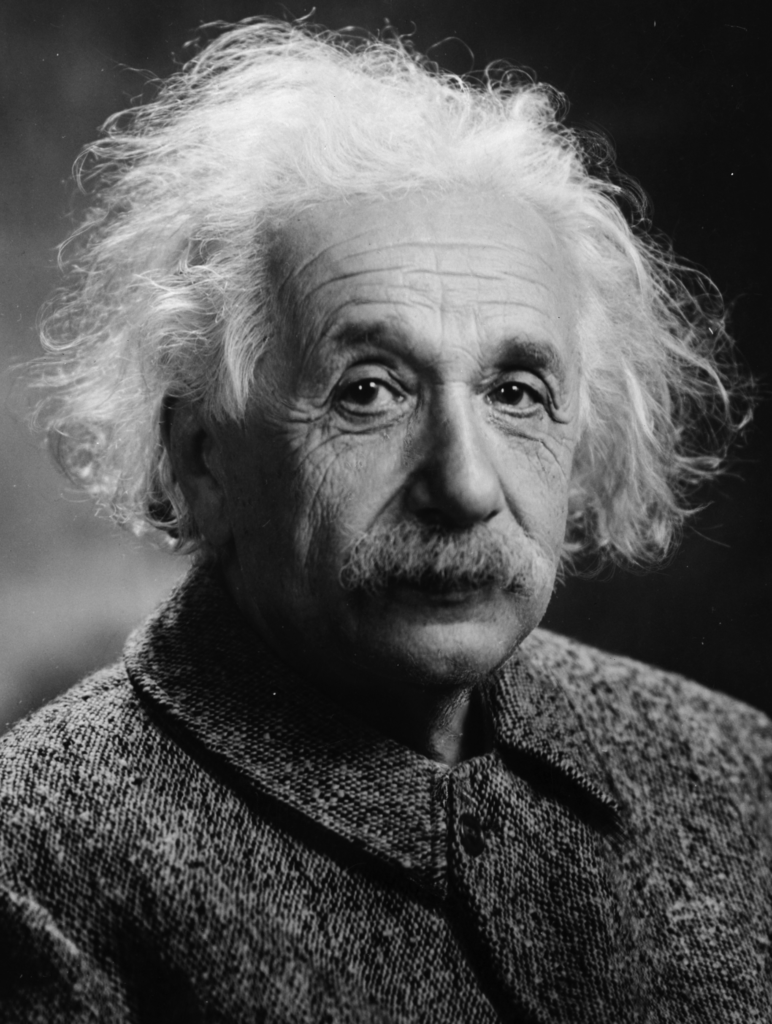

News of Eddington’s verification of Einstein’s Theory spread like a tsunami from Europe across the Atlantic, reaching the front page of The New York Times on November 10, 1919. In the days that followed, the tsunami continued across middle America to California, carrying with it the name “Albert Einstein.” Science and technology that had been dedicated to the development of weapons was now elevated to the loftier goal of universal enlightenment. Einstein became its champion and an overnight celebrity. It took 14 years after publication of his first paper on Relativity for Einstein to become “an overnight success.”

Once the scientific community endorsed Einstein’s theories, public opinion followed. Those who were not well-versed in physics or math or who had no comprehension of his theories turned out to huge rallies of more than 15000 people when Einstein visited America in 1921. On his second visit to America, Albert and his wife Elsa were invited to the black-tie premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s famous film City Lights. As Chaplin and Einstein entered the theater to thunderous applause, Chaplin observed, “They cheer me because they all understand me, and they cheer you because no one understands you.”