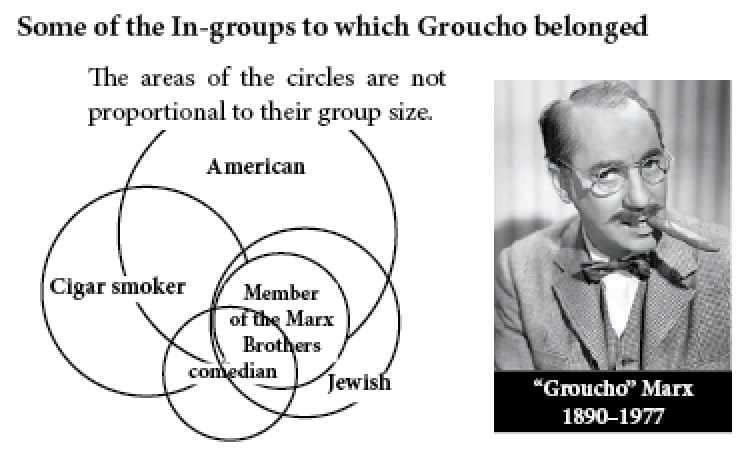

Waxing eloquent on group membership, comedian Julius “Groucho” Marx famously said, “I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member.” In spite of his assertion, Groucho belonged to a variety of in-groups. As one of 5 brothers born in Manhattan to Jewish parents of German and French extraction, his membership in the Marx family, the Jewish community, and the American in-group were automatic, while his membership in the comedian and cigar smoking in-groups were selected. Out of Groucho’s complex mix of in-groups emerged his unique persona, prompting Irving Berlin to say in rhyming couplet, “The world would not be in such a snarl, had Marx been Groucho instead of Karl.”

The Family: The Smallest In-group

Driven by the need for sex and companionship, individuals pair and produce offspring, creating the smallest human tribe known as a “family.” This is called a kin selection in-group because it defines a subgroup of human society that is connected by shared ancestry and cultural values. The binding force of this in-group is empathy. Like the nuclear strong force that holds the nucleus of the atom intact, empathy draws family members together, enabling them to share each other’s pain, suffering, and joy. It is most powerfully manifest in maternal love. During pregnancy, oxytocin plays a major role in preparing the mother for lactation and promoting maternal-infant bonding. Oxytocin and other hormones play a significant role in generating the loyalty and altruistic behavior that is capable of prevailing over self-interest, thereby strengthening family bonds. It is from the family unit, connected by shared genetic material, that most people derive their sense of self and identity.

Beyond the family, from which we develop our biological characteristics, are the races and nationalities with whom we identify because of our similarities.

The O.J. Simpson trial in 1994 revealed the extent to which racial identity influenced perception. In spite of compelling DNA evidence, Simpson’s lawyer, Johnny Cochran was able to play on the black jurors’ mistrust of police, convincing them that the DNA evidence may have been a police fabrication. When the “not guilty” verdict was announced, stark demarcations between the Black and White perspectives emerged. A poll in late 1995, revealed that 72% of Whites and about 29% of Blacks believed that Simpson was guilty. Geoffrey Cohen, Professor of Psychology at Stanford, suggested that this difference in perception resulted from the natural attempt to affirm deeply held attitudes and beliefs. He asserted:

The conflicting attitudes that Blacks and Whites had about the O. J. Simpson trial might also have arisen, in part, from a desire to affirm racial identity and solidarity. Evidence that challenges the validity of such cherished beliefs presents a self-threat insofar as giving up that belief would entail losing a source of esteem or identity. To neutralize that threat, people are apt to evaluate evidence defensively.

Empathy Bonds all In-groups and Reaches Beyond

Distinct from biological influences such as kin and racial selection is group selection whereby individuals with shared goals or beliefs meld into an in-group. Like the family, in-groups such as sororities, religious sects, country clubs, book clubs, and even motorcyle gangs are bonded by an oxytocin-generated empathy.

Researchers have discovered that empathy is often expressed by an almost imperceptible mimicry of each other’s facial expressions. When one member of an in-group smiles, the facial muscles of the other members, through a process called “mirroring,” emulate an involuntary semblance of a smile. Though these facial movements are barely visible, the brain perceives these empathetic reactions, reinforcing the feelings of solidarity throughout the group. As Darwin observed, empathy is particularly evident among members of the military, who will risk death to save a member of their group. Each individual surrenders some autonomy to gain protection, emotional support, and in some cases, more power as a part of something bigger. Such cooperation has been the cornerstone of human progress from hunting in groups to the development of modern technology.

So while our sense of self and our identity are strongly determined by our biological heritage, we also derive a component of our identity from group selection that is independent of our biology. This enables us in some cases to feel more empathy and connection to an individual outside our biological heritage than to some of those who share our biological heritage.