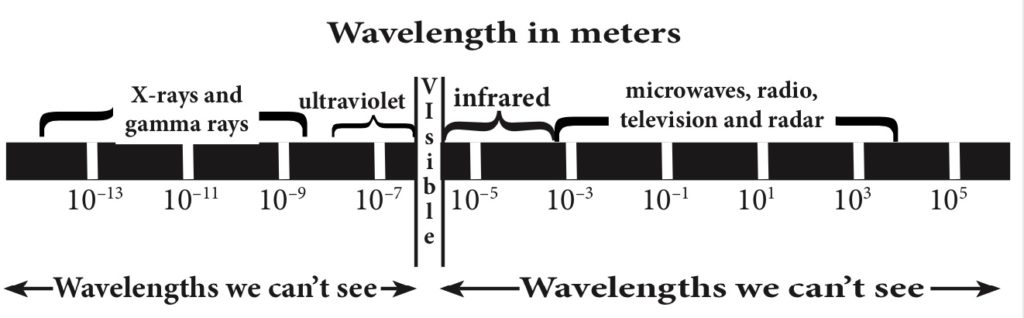

Each of us is little more than a brain receiving information through our senses from an external world. Between us and the stimuli that reach our receptors is a large abyss that must be bridged by a process that “makes sense” of the incoming data. From birth we are gifted with a growing cognitive capacity to organize this information into stored memories and learned concepts. But this representation is fraught with flaws and inaccuracies that derive from two factors. The first of these is physiological. Our senses grasp only a small fraction of the information that is present in the external world. For example, eyesight, the main sense from which we derive information, perceives only the minute fraction of electromagnetic wavelengths, in the narrow vertical interval on this logarithmic scale.

All of these types of radiation, except those in that tiny vertical interval, are invisible and would be unknown to us without our invented tools. Similarly, we humans hear only a small fraction of wavelengths of sound. We cannot even imagine what other natural phenomena exist outside the range of all our senses. Adding to our isolation is the fact that even within the range our senses, we experience reality indirectly.

The second factor obscuring our perception of reality is manifest in the biases that are hardwired by evolution into our cognitive machinery. While these perceptual distortions arose to enhance our chances of survival, they carry some side effects that distance us from objectivity. For example, in some cases our senses sacrifice accuracy for speed, giving us fast-and-biologically-frugal approximations that present a flawed representation of reality.

This ability to synthesize pixels into a complete shape is one of the most important visual acuities that we acquired through evolution. It is through this unconscious cognitive process that we are able to distinguish a predator camouflaged against a background of similar colors and textures. Detecting a venomous snake hiding in the weeds by a pond, or identifying a tiger with stripes that merge with the shadows of bamboo shoots, has often meant the difference between life and death. Though we all have the capacity to synthesize pixels into whole entities, individuals often compose different perceptions from the same image. What animal do you see in this photo? Answer before you read ahead.

On August 18, 2019, Dan Quintana, a scientist at Norway’s University of Oslo, posted a video with the caption: “Rabbits love getting stroked on the nose.” The video went viral with viewers asserting that this was not a rabbit, but rather a raven. Two years earlier, Paige Davis, a curator at the World Bird Sanctuary in Missouri had posted this video of a raven named Mischief, who lived up to its name. When asked how Mischief was responding to his new celebrity status, the Sanctuary reported that he’s ravin’ about it. Can you see the alternative perception?

Humans have been intrigued by optical illusions as far back as the 5th century B.C. when Epicharmus of ancient Greece attempted to explain visual ambiguity. Illusions reveal that things are not always as they first appear, challenging our natural tendency to believe that what we see is reality. Most of reality is invisible to us, but even what we see often leads to ambiguous interpretation.