You raise an important question. This week, AP News reported that “CEOs made nearly 200 times what their workers got paid last year.” In an extreme case, Tim Cook, CEO of Apple made just over $60M last year which is about 672 times the median annual salary of an Apple employee. Is this fair?

Many people feel outraged by what would appear to be a gross inequity. An academic colleague of mine used to argue that no person is worth more the four times anyone else. We took our discussions to the golf course where we could have a leisurely game and a gentle conversation. Although I suspected he was envious of the incomes of corporate executives, I would appeal to his rational side by suggesting that his multiple of “four times” might be reasonable in comparing the output of people working with pick and shovel. However, the information age has brought with it exponential differences in what people can achieve.

A brain surgeon who can use advanced technologies to perform an operation to save a person’s life is worth substantially more than a hospital orderly. My friend would object with, “Yes, but that brain surgeon’s education was possible because tax dollars from the citizenry created the university in which he developed his skill.” He was probably unaware that 45.8% of total income taxes collected by the IRS in 2021 came from the top 1% of Americans while less than 3% of total taxes came from the bottom half of income earners. (see: Summary of the Latest Federal Income Tax Data, 2024 Update )

In a third attempt to explain the leverage of intellect combined with technology, that makes some people much more valuable than others, I suggested, “Suppose you were on the Board of PepsiCo Inc., hiring a new CEO, and there was a person whose record suggested he or she could increase your sales by 3%. How much would that be worth to your company?” (In 2023, PepsiCo sales were about $91.5 billion.)

My good friend challenged the premise of the question stating, “Surely, no individual can make that much difference in a companies sales.” Of course, my friend was a very intelligent individual and highly knowledgeable in his field, but he knew little about business and the observations of some of the great CEOs about the high premium they placed on competence.

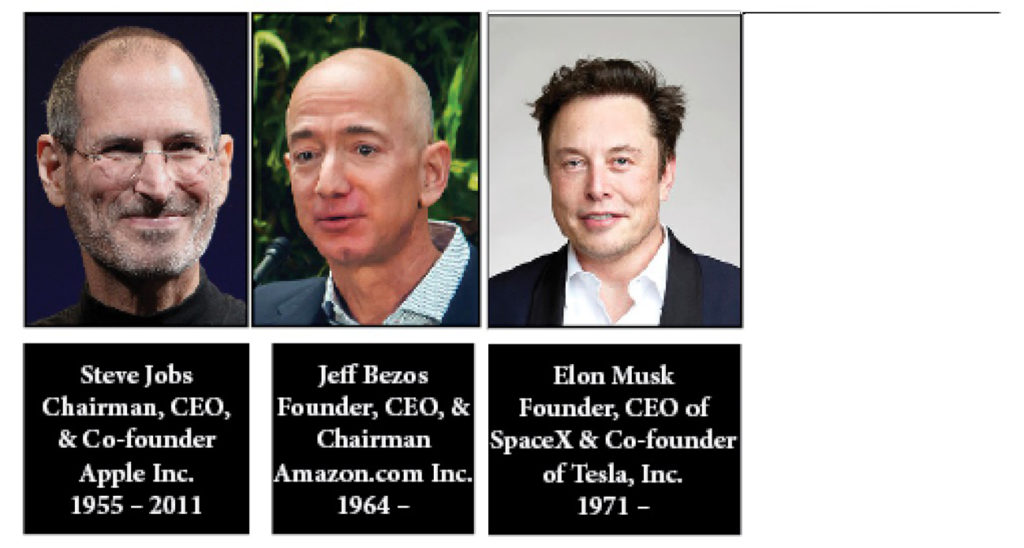

Steve Jobs, founder of Microsoft’s major competitor, Apple Inc. explained in an interview with Business Week on October 12, 2004, one of the secrets of his success in hiring employees.

I noticed that the dynamic range between what an average person could accomplish and what the best person could accomplish was 50 or 100 to 1. Given that, you’re well advised to go after the cream of the cream … A small team of A+ players can run circles around a giant team of B and C players.

Jeff Bezos echoed the comments of Jobs in emphasizing the importance of IQ as the most vital element sought in Amazon’s recruitment and hiring of their top people. Leibovich, a biographer of Bezos, observed:

The philosophies Bezos applied at Amazon follow a principle he has long embraced: Intrinsic ability [IQ] rules, trumping acquired skills [EQ] and accumulated experience.

In a 2014 interview, Elon Musk, when asked, “When you hire people, what skills do you want them to have?” responded, “What I’m really looking for is evidence of exceptional ability.” If we were to sample most of the top corporations today, including investment companies as well as hi-tech innovators and lower tech retailers, we would get similar responses.

In Coming Apart: The State of White America 1960–2010, Charles Murray states:

Over the last century, brains became much more valuable in the marketplace. … What was someone with exceptional mathematical ability worth on the job market a hundred years ago if he did not have inter-personal skills or common sense? Not much. … What is a person with the same skill set worth today? If he is a wizard programmer, as people with exceptional mathematical ability tend to be, he is worth six figures to Microsoft or Google. If he is a fine pure mathematician, some quant funds can realistically offer him the prospect of great wealth.

Murray further explained that, not only mathematicians, but corporate managers with higher cognitive abilities and the potential to increase productivity or market share by a few percent, can earn for a company huge multiples of their own salaries, and this “makes brains worth more in the marketplace.”

“Fairness” is an elusive concept. For some in means equity, captured in the mantra “to each according to his needs, from each according to ability.” For others it means putting a cap on extreme wealth. For still others, it’s about rewarding people in proportion to their yield. Perhaps the best answer is to examine what economic systems throughout the world produce the best for the most.