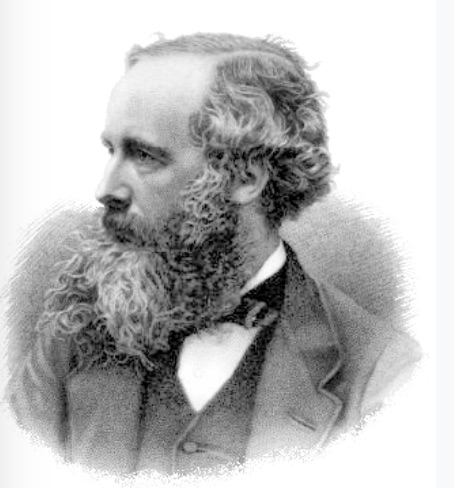

James Clerk Maxwell, born on June 13, 1831 in Edinburgh, Scotland displayed an intense curiosity from an early age. Acutely interested in mechanisms like door locks, keys, and water pipes he would ask, “What’s the go o’ that?” meaning, “How does it work?” Recognizing his precociousness, his mother introduced him to the writings of John Milton and by age eight he could recite long passages from Milton’s works.

In 1842, when James was 10 years old his father took him to Robert Davidson’s demonstration of electric propulsion and magnetic force–an experience that would have a profound effect on how James Clerk Maxwell’s life would unfold. At that time James was enrolled in the prestigious Edinburgh Academy, where he was experiencing the social difficulties with classmates, that is common among children of high intelligence. Fascinated by geometry, he discovered, without formal instruction, the regular polyhedra and at age 13 he won the school’s medal for mathematics and first prize in both English and poetry. At age 14, he wrote a scientific paper describing how to construct ellipses and Cartesian ovals using a string.

Between 1847 and 1850, James attended the University of Edinburgh where he was acquiring a mastery of mathematics while also conducting experiments that led to the publication of two research papers in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. On graduation, he enrolled at the University of Cambridge and four years later, graduated with a degree in mathematics and the distinction of Second Wrangler. In February 1856, at the tender age of 24, Maxwell was appointed Chair of Natural Philosophy [i.e., Science] at Marischal College, Aberdeen and in 1860, when Marischal College was merged with another university, he became the Chair of Natural Philosophy at King’s College, London. It was during this time that Maxwell was influenced by Michael Faraday, and began to explore the relationship between electricity and magnetism. Discovering that the speed of propagation of a magnetic field is approximately the speed of light, Maxwell concluded, “We can scarcely avoid the conclusion that light consists in the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena.” [i.e., electric and magnetic fields are propagated in planes perpendicular to one another.] In his epoch-making paper On Physical Lines of Force published in March 1861, Maxwell captured the interconnected behaviors of electricity and magnetism in a linked set of differential equations with 20 equations in 20 variables–later condensed into four partial differential equations, now known as Maxwell’s equations. Maxwell died in Cambridge of abdominal cancer on November 5, 1879 at the young age of 48, yet his equations have been described as the greatest achievement of 19th century physics. A polymath whose interests spanned a broad range of topics in science, Maxwell once observed, All the mathematical sciences are founded on relations between physical laws and laws of numbers.