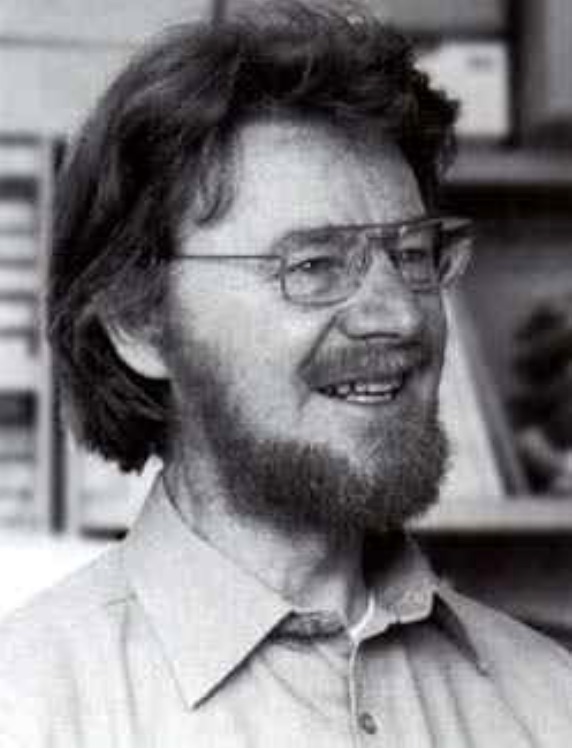

John Stewart Bell was born on July 28, 1928 in Belfast, Ireland. At 11 years of age, he decided to become a scientist, and 5 years later, enrolled at the Queen’s University of Belfast, majoring in experimental physics. In 1956, he was awarded a Ph.D. by the University of Birmingham specializing in nuclear physics and quantum field theory. Apparent contractions in the interpretation of quantum “weirdness” troubled him to the extent that he continued to ruminate on the problem in the years that followed.

In 1935, the year that Schrödinger had introduced the gedanken experiment involving the superposition of the cat’s states of existence, Einstein and two colleagues, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen proposed another gedanken experiment, now known acronymically as the EPR paradox. To show the perceived flaw in the Copenhagan concept of superimposed states, they had proposed a situation in which two elementary particles locked in a no-spin pairing suddenly fly apart. Since the particles were originally part of a no-spin pair, they must have opposite spin. After the particles are a million miles apart, a physicist measures the spin of one particle and discovers that it is spinning clockwise in a certain direction. This tells her that the other particle is spinning counterclockwise. When another physicist investigates the spin of the other particle he verifies that, indeed, it is spinning in the opposite direction. There are two possible interpretations of what happened:

a) Each particle was simultaneously in two superimposed states: spin up and spin down. The measurement of the one particle caused the collapse of the two states into a definite state, causing the other particle to collapse also into the opposite state, by some mysterious communication at a distance.

b) The two particles had definite spins that were opposite at the outset, so measuring the spin of one particle was enough to deduce the spin of the other.

In their EPR paper, Einstein and his coauthors dismissed explanation “a” as untenable, since this would imply that previously connected particles could interact with each other instantaneously when separated by great distances. But alternative explanation “b” left unanswered the question, “If quantum physics is complete, why can’t it predict the spin state of the particles before measuring them?” Einstein and others who were reluctant to abandon determinism, suggested that other hidden variables that quantum physics had not yet identified would eventually restore determinacy to quantum physics.

By 1960, John was working at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN, Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire), in Geneva, Switzerland, where he worked on theoretical particle physics and on accelerator design, while also investigating the foundations of quantum theory. The Copenhagen interpretation had languished in limbo until, in 1964, John published a remarkable result now called Bell’s Theorem. In his paper On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox, he deduced, using simple logic and the quantum properties of spin, that if it were possible to predict the spin of an elementary particle without measuring, then it would lead to a logical contradiction. This invalidated interpretation “b” and with it, the EPR hope that a method of predicting the spin of an elementary particle was possible. Physicists were compelled to accept interpretation “a”, that the particles, even when separated by large distances, are interconnected. This interconnectedness, now called entanglement, was later verified by experiment. Though originally supportive of Einstein’s interpretation, Bell eventually stated, “Bohr was inconsistent, unclear, willfully obscure and right. Einstein was consistent, clear, down-to-earth and wrong.”