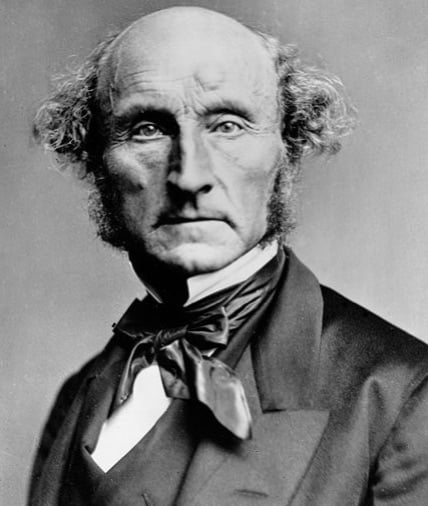

John Stuart Mill was born in London, England on May 20, 1806, to Harriet Barrow and James Mill, a Scottish economist and historian. Striving to make his son a genius, James Mill kept John away from people his own age and subjected him to a rigorous education during his early years. By age 3, John Stuart Mill had learned enough Ancient Greek to embark upon an ambitious reading program that included Aesop’s Fables, the complete works of Herodotus, and the dialogues of Plato. By age 8, he was studying Latin and poring through Euclid’s geometry and courses in algebra.

At 13 years of age, John was introduced to political science, immersing himself in the works of political economists, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus. Adam Smith had published, in 1776, his seminal treatise The Wealth of Nations, in which he asserted that the wealth of a country was not determined by its gold reserves, but rather by the production of its workers. (currently measured as GDP). John embraced Smith’s economic theories, and in 1821, at the age of fifteen, he helped his father write Elements of Political Economy. Combined with the belief that a government should strive for “the common good,” this conception of wealth meant that economic policy should maximize the productivity of its workers. Achieving this would require the state to operate a free-market system, wherein the natural laws of production and exchange (often referred to as “the invisible hand,”) would guarantee an equitable market.

At age seventeen, John was given a job, working under his father’s direction at the East India Company in London, England. However, the years of relentless striving to learn, purging emotion in favour or rational disinterested analysis, began to drain John’s energy. In the autumn of 1826, when he was just 20 years of age, he fell into a deep depression, described in his autobiography:

It was in the autumn of 1826. I was in a dull state of nerves, such as everybody is occasionally liable to; unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent… my heart sank within me: the whole foundation on which my life was constructed fell down. All my happiness was to have been found in the continual pursuit of this end. The end had ceased to charm, and how could there ever again be any interest in the means? I seemed to have nothing left to live for.

In chapter V of his autobiography, he went on to describe in some detail how his appetite for approbation that had previously brought him pleasure, he been sated at too early an age and with its disappearance had come a sense of purposelessness and hopelessness:

The fountains of vanity and ambition seemed to have dried up within me, as completely as those of benevolence. I had had (as I reflected) some gratification of vanity at too early an age: I had obtained some distinction and felt myself of some importance, before the desire of distinction and of importance had grown into a passion: and little as it was which I had attained, yet having been attained too early, like all pleasures enjoyed too soon, it had made me blasé and indifferent to the pursuit. Thus neither selfish nor unselfish pleasures were pleasures to me. And there seemed no power in nature sufficient to begin the formation of my character anew, and create, in a mind now irretrievably analytic, fresh associations of pleasure with any of the objects of human desire.

In the years that followed, he gradually emerged from this depression, inspired by the poems of Wordsworth and others who reconnected him with the joy of beauty in the world. Then, in 1830, he met Harriet Taylor with whom he shared a Platonic relationship until after her husband’s death in 1849. They married in 1851, initiating a period of Mill’s greatest productivity. A series of publications on a wide variety of topics including poetry, history, economics and politics followed during the 1830’s and beyond. These include A System of Logic (1843), The Principles of Political Economy (1848), and his celebrated On Liberty (1859). In this classic, he warns of the potential danger of a democratic government becoming a “tyranny of the majority” and emphasizes the importance of individual rights.

John Stuart Mill was strongly influenced by his wife, Harriet who worked with him on the writing of On Liberty. She died just before its publication. Through his exposure to Harriet’s ideas, Mill became an advocate for women’s rights in addition to his earlier position as an abolitionist. Influenced by Thomas Malthus, he warned that unlimited growth would lead to environmental destruction. Expressing his lifelong commitment to individual freedom, he stated:

So long as we do not harm others we should be free to think, speak, act and live as we see fit, without molestations from individuals, law, or government.