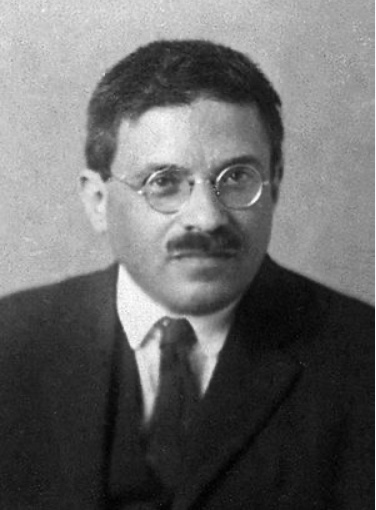

Paul Ehrenfest was born in Vienna on January 18, 1880 to Jewish parents from Lostice, in the current Czech Republic. The family, consisting of parents Sigmund and Johanna Ehrenfest (née Jellinek), and their five sons ran a grocery store. Paul, the youngest of the five boys, suffered poor health from his early years. He was sickly, plagued with dizzy spells, and suffering frequent nosebleeds that made him a target of anti-Semitic comments from other children in the neighbourhood. When Paul was 5 years old, his oldest brother was twenty-two. Yet, it was through their mentoring of his older siblings that Paul developed an interest in science and particularly in solving puzzles.

By the time he was six years old Paul had taught himself, with some help from his mother, how to read, write and count. In 1886, he enrolled in primary school, graduating four years later. Though his report cards reveal that he achieved top marks in all subjects, it was evident that his life was increasingly encumbered by a series of emotional challenges. His mother died of breast cancer in 1890 and his father was suffering from stomach ulcers. When Paul’s mother died, his father married Paul’s aunt–Johanna’s younger sister.

After his mother’s death, Paul enrolled at the Akademisches Gymnasium, where his performance in all subjects, except mathematics, plummeted, reflecting his dismal home life and his personal depression. When Paul’s father died of the stomach ailments that had plagued him in the last few years, Paul considered dropping out of school, but his oldest brother Arthur persuaded him to continue on.

In 1899 at the age of 19, Ehrenfest completed his secondary school education and enrolled at the Technische Hochschule in Vienna. Like many bright children who feel isolated, he found friends at his intellectual level with whom he bonded, dubbing themselves as “the inseparable four.” Between 1899 and 1900, Ehrenfest was inspired by the lectures of Ludwig Boltzmann on the mechanical theory of heat–an experience that kindled in him a passion for the study of mathematical physics.

Paul Ehrenfest eventually became a brilliant physicist who worked with Einstein and proved that the general theory was incompatible with the principle of the equivalence of gravitational and inertial forces. Ray Monk, biographer of Robert Oppenheimer, observed, “Ehrenfest’s greatest concern in physics was always with attaining clarity, genuine understanding.” As he worked on the general theory and quantum physics, Ehrenfest began to feel uneasy about the high level of mathematical abstraction, and felt that he no longer understood these theories with sufficient clarity. This recognition weighed heavily on his mind, making him feel inadequate and unworthy of his prestigious post at the University of Leiden in Holland. He sunk into a deep depression. Then, on September 25, 1933, he visited his son, Wassik who was afflicted with Down syndrome. There in Vondelpark in Amsterdam, Paul Ehrenfest, in a state of hopeless depression shot his son and then turned the gun on himself. A suicide note was found that he had written, but not sent, to Einstein, Danish physicist Niels Bohr, and a few other close friends After describing how unbearable his life had become, he wrote:

In recent years it has become ever more difficult for me to follow the development in physics with understanding. After trying, ever more enervated and torn, I have finally given up in desperation. This made me completely weary of life … I did feel condemned to live on mainly because of the economic cares for the children. I tried other things, but that helps only briefly. Therefore, I concentrate more and more on the precise details of suicide. I have no other practical possibility than suicide, and that after having first killed Wassik. Forgive me …

Between the time that Ehrenfest became passionate about physics and the time of his suicide, physics had become less connected to real-world models like electrons rotating around the nucleus of a molecule, to abstract mathematical representations with no real-world models, rendering him feeling as out-of-place in physics as he was when a friendless child in elementary school. The isolation was too much for him to bear and he opted out of life. Even the most brilliant members of our species suffer the emotional traumas familiar to us all.