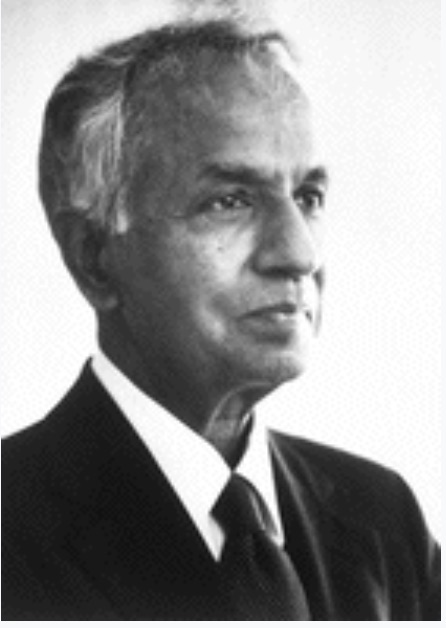

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar was born on October 19, 1910 in Lahore, India (modern day Pakistan). Chandra, as he was affectionately known, grew up in Madras, India where he received his schooling. At an early age, he was inspired by the achievements of his paternal uncle Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman who is immortalized for his discovery in 1928 of the Raman effect–the change in wavelength of light that occurs when it collides with molecules.

Until age 12, Chandra was tutored at home, and was subsequently schooled in mathematics and physics by his father. He subsequently attended a Hindu high school in Madras and in 1925 enrolled at the University of Madras.

During his undergraduate years at the University of Madras, Chandra published his first research paper, The Compton Scattering and the New Statistics that was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society. In 1930, the year that his uncle was awarded a Nobel Prize for his discovery of the Raman effect, Chandra received a scholarship from the Indian government, enabling him to continue post graduate studies at Trinity College, Cambridge. During his voyage from India to England, he completed the calculations indicating that a star of a mass greater than 1.4 times that of the Sun (now known as the Chandrasekhar’s limit) would eventually collapse into an object of enormous density (later called a “white dwarf”) unlike any object known to exist. From 1933 to 1937 he continued his research at Cambridge, punctuated with visits to Göttingen and Copenhagen, where he met Niels Bohr. In 1937, Chandra went to America and joined the faculty at the University of Chicago where he remained the rest of his life.

In the decades that followed, Chandra explored a wide variety of topics including stellar structure, radiative transfer, the stability of relativistic stars and eventually the mathematical representation of black holes, and models of colliding gravitational waves. He was prolific, having published more than 400 research papers and books on a wide variety of topics. In 1983, Chandra was awarded the Nobel prize for Physics for his studies on “the physical processes important to the structure and evolution of stars. In his book,” The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes, Chandra states:

The black holes of nature are the most perfect macroscopic objects there are in the universe: the only elements in their construction are our concepts of space and time. And since the general theory of Relativity provides only a single unique family of solutions for their descriptions, they are the simplest objects as well.