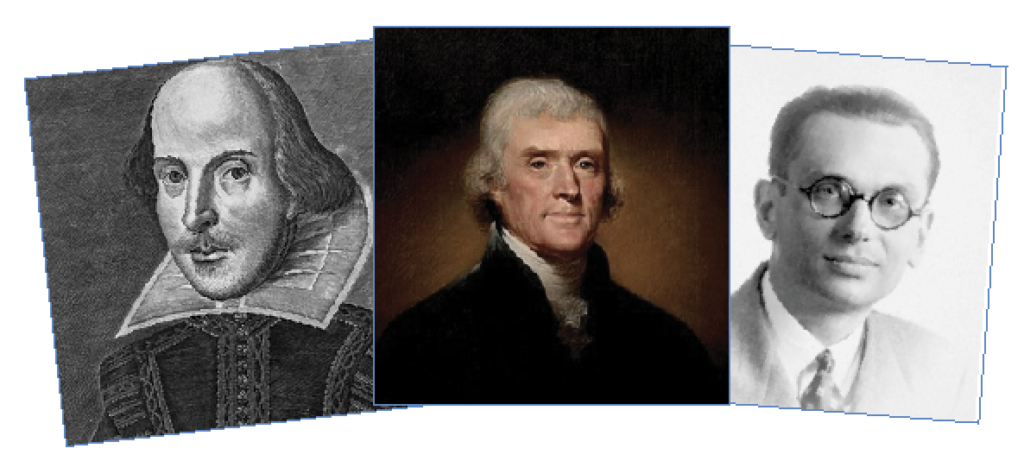

Can you identify these three people?

All three intellectual giants you see in the collage were born in April, yet only two will be immediately recognizable to most people, and the third–an enigma. On April 13, we will post a brief tribute to Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States and architect of the Declaration of Independence, who was born on April 13, 1743. Addressing an elite group of intellectuals at a dinner honoring American Nobel Prize winners, the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, opined:

I think that this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

Indeed, in every assessment ranking the intelligence of U.S. Presidents, Jefferson comes at or near the top. Similarly, in every ranking of the greatest authors of English literature, the name William Shakespeare stands at or near the top. This unparalleled playwright, poet and actor was baptized on April 26, 1564 and presumed born on April 23, 1564, though there is no specific evidence of his birth date. His remarkable insight into human nature and his exceptional ability to capture his insightful observations in succinct, yet poetic phrase, had made his plays the gold standard for theater for more than 500 years. His image has become an icon for English literature.

If you were able to identify that third face, you are a member of an elite collection of math and science nerds who recognize the man who shook the foundations of mathematics. On April 28, 1906, Kurt Gödel was born in Brünn in Austria-Hungary. At age 25, he published his doctoral thesis, On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems. In this epoch-making paper, Gödel enunciated a theorem and corollary that registered a magnitude ten on the seismometer of mathematical quakes. The programs of both the formalists and the logicists collapsed like giant skyscrapers whose foundations had crumbled under a tectonic shift. Though it took many years for the mathematics community at large to appreciate what Gödel had achieved, those who were working in the foundations of mathematics soon recognized the far-reaching implications of his powerful theorem and corollary. The brilliant wunderkind, John von Neumann, who had published The Axiomatization of Set Theory in 1928, was one of the first to perceive the “truth and importance of Gödel’s work.” Others soon followed and the initial shock wave eventually dissipated into a universal acceptance that absolute certainty of anything may be an illusion.

After receiving his doctorate at the University of Vienna, Kurt Gödel became a privatdozent (an unpaid lecturer) at that institution. When, in June 1936, a colleague was assassinated by a former student, Gödel suffered what was described as a “severe nervous crisis” manifest in paranoid symptoms, including a fear of being poisoned. He subsequently spent months in a sanitarium for nervous disorders and depression.

In 1938, his application for a paid position at the University of Vienna was rejected. The next year, jobless, and fearing conscription into the German army, he emigrated to the United States with his wife Adele. His fame as a brilliant mathematician earned him a temporary appointment (with annual renewals) to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton where he developed a close friendship with Albert Einstein.

As a person, Kurt Gödel was as enigmatic as his arcane theorem. While mathematicians populate the full spectrum from introvert to extravert, Gödel defined a new category at the introvert end of the scale. In her book about Gödel and his theorem, Rebecca Goldstein writes:

Kurt Gödel struck almost everyone as seriously strange, presenting a formidable challenge to conversational exchange…John Bahcall was a promising young astrophysicist when he was introduced to Gödel at a small Institute dinner. He identified himself as a physicist, to which Gödel’s curt response was, ‘I don’t believe in natural science.”

Following his permanent appointment to the Institute in 1946, Gödel decided to apply for citizenship. Taking seriously his preparation for the citizenship exam, Gödel pored over the US Constitution with a fine-tooth comb, when he stumbled upon what he believed to be an inconsistency that could allow the democracy to degenerate into a dictatorship. In 1971 Oskar Morgenstern, a mathematician at Princeton, recounted what has become one of the most popular anecdotes in the lore of eccentric mathematicians. It was December 5, 1947–the day that Einstein and Morgenstern accompanied Gödel to his citizenship exam.

On that particular day, I picked up Gödel in my car. He sat in the back and then we went to pick up Einstein at his house on Mercer Street…While we were driving, Einstein turned around a little and said, “Now Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Of course, this remark upset Gödel tremendously, which was exactly what Einstein intended and he was greatly amused when he saw the worry on Gödel’s face.

[When we arrived at the immigration office], we were invited to sit down together, Gödel, in the center. The examiner first asked Einstein and then me whether we thought Gödel would make a good citizen. We assured him that this would certainly be the case, that he was a distinguished man, etc.

And then he turned to Gödel and said, Now, Mr. Gödel, where do you come from?

Gödel: Where I come from? Austria.

The examiner: What kind of government did you have in Austria?

Gödel: It was a republic, but the constitution was such that it finally was changed into a dictatorship.

The examiner: Oh! This is very bad. This could not happen in this country.

Gödel: Oh, yes, I can prove it.

So, of all the possible questions, just that critical one was asked by the examiner. Einstein and I were horrified during this exchange; the examiner was intelligent enough to quickly quieten Gödel and broke off the examination at this point, greatly to our relief.

The friendship between Einstein and Gödel deepened in their years together at the Institute for Advanced Study, so that each became the other’s best friend. They took long walks together discussing philosophy, mathematics, and physics. In a Festschrift volume organized to honor Einstein’s 70th birthday, Gödel submitted a paper that contained an unconventional solution to Einstein’s gravitational equations that allowed for backward travel in time.

When Einstein died of heart failure on April 18, 1955, Gödel felt increasingly alone and alienated from his colleagues at the Institute. In the decades that followed, his earlier signs of paranoia returned and he began suspecting once again that his food was being poisoned. His wife, Adele became his food taster. Gödel came to believe that his doctors were part of a conspiracy to kill him and he began to restrict his intake of food. On December 29, 1977, he entered Princeton Hospital at an estimated weight of sixty-five pounds. His self-imposed starvation had taken its toll. Kurt Gödel died on January 14, 1978. The death certificate stated that he died of “malnutrition and inanition” caused by “personality disturbance.”

In 1978, an article in The New York Times described Gödel’s Theorem as “the most significant mathematical truth of this century, incomprehensible to laymen, revolutionary for philosophers and logicians.” A symbol-free expression of this theorem and its corollary can be found in the book Intelligence: Where we Were, Where we Are & Where we’re Going.