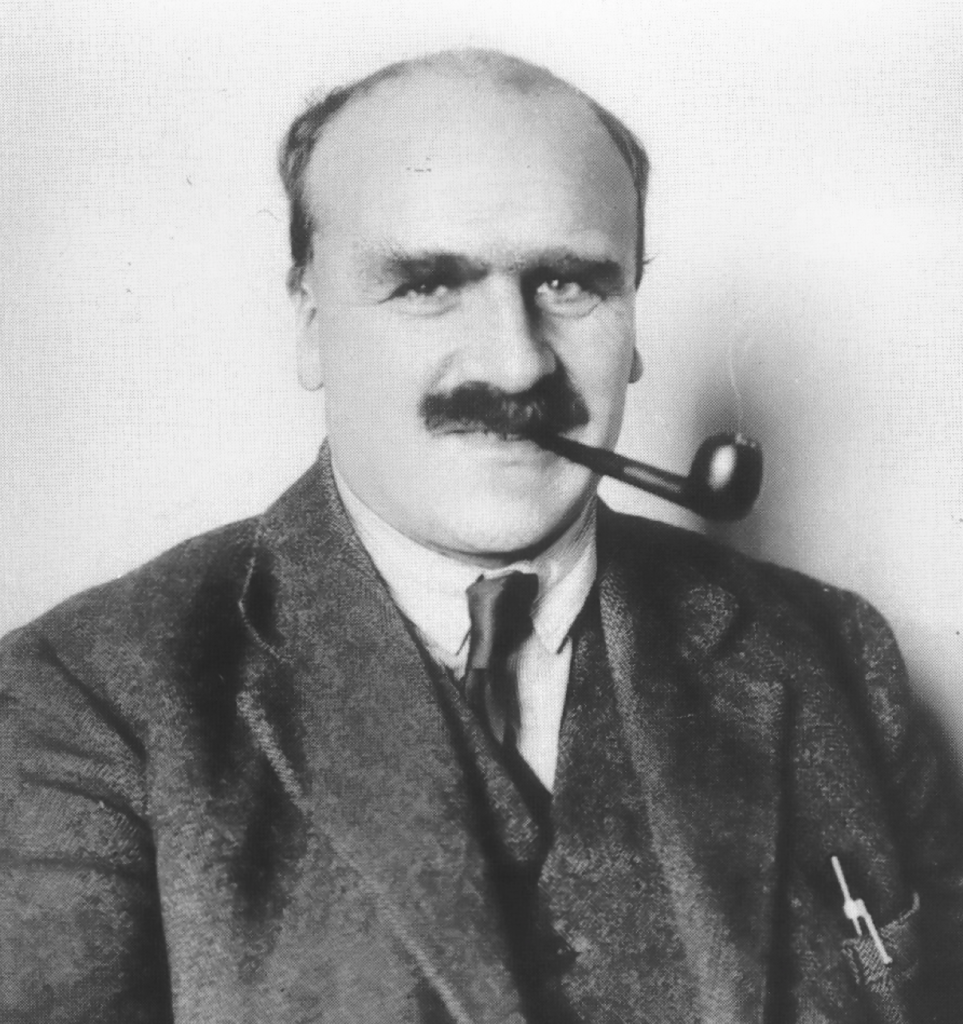

In 1946, J.B.S. Haldane, an English scientist stated:

We cannot in general say that A has a greater innate ability than B. A might do better in environment X, and B in environment Y. Had I been born in a Glasgow slum I should very probably have become a chronic drunkard, and if so, I might by now be a good deal less intelligent than many men of a stabler temperament but less possibilities of intellectual achievement in a favourable environment. If this is so it is clearly misleading to speak of the inheritance of intellectual ability. This does not mean that we must give up the analysis of its determination in despair. It means that the task will be harder than many people believe.

The task in determining the extent to which genetic potential interacts with environment to create our ultimate intelligence has, indeed, proved to be difficult. In the latter half of the 20th century, as the egalitarian movement gained momentum, the nurturist view of intelligence became mainstream in the field of psychology. Many argued that intelligence was purely environmental and there was no genetic component.

In 1990, Thomas J. Bouchard et al. published a seminal article titled, Sources of Human Psychological Differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart19in which they assembled 100 sets of identical twins who were separated early in life and raised apart. All participants in the study completed about 50 hours of medical and psychological assessment.

Since identical twins come from a single fertilized egg, they share virtually 100% of their alleles and can be considered to be genetically identical. Furthermore, since they were raised apart, the differences in their IQ, when tested at the end of their separation could be entirely attributable to environmental factors.

Since the twins in the Minnesota study were raised apart, no part of the correlation in the IQ scores of twins could be attributed to shared experiences. Hence, Bouchard et al. were able to estimate the difference in IQ attributable to genetics, using the correlation in the IQ scores of the twins. The researchers reported “about 70% of the variance in IQ was found to be associated with genetic variation.” The authors cautioned that this finding did not imply that IQ cannot be enhanced by rich experiences. In fact, they cited the Flynn Effect as evidence that IQ scores can be increased by environmental influences. At least 5 subsequent studies involving samples of identical twins in the United States and Europe, who were reared apart, yielded heritabilities of IQ between 0.68 and 0.71, confirming the findings in the Minnesota study.John Sedgwick, an advocate for the idea that environment plays a strong role in intelligence, conceded:

As for IQ’s genetic component, enough twins studies agree that heritability accounts for somewhere in the vicinity of 50% to 70% of intelligence, with 60% the most likely figure, which of course still leaves ample room for environmental influence.

In 2011, a large group of researchers published the results of a genome-wide analysis of 549,692 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) involving 3511 unrelated adults. (An SNP represents a difference in a single DNA building block, called a nucleotide.) They reported:

Our results unequivocally confirm that a substantial proportion of individual differences in human intelligence is due to genetic variation, and are consistent with many genes of small effects underlying the additive genetic influences on intelligence. … [Furthermore] purely genetic (SNP) information can be used to predict intelligence.

This research estimated the heritability of IQ to be about 0.5, confirming the results of the studies involving twins. Its conclusion that general intelligence is polygenic, i.e., it derives from a combination of many genes supports the concept of intelligence as a multi-faceted characteristic. Maybe Haldane’s intellectual potential was also a factor saving him from becoming a “chronic drunkard.”