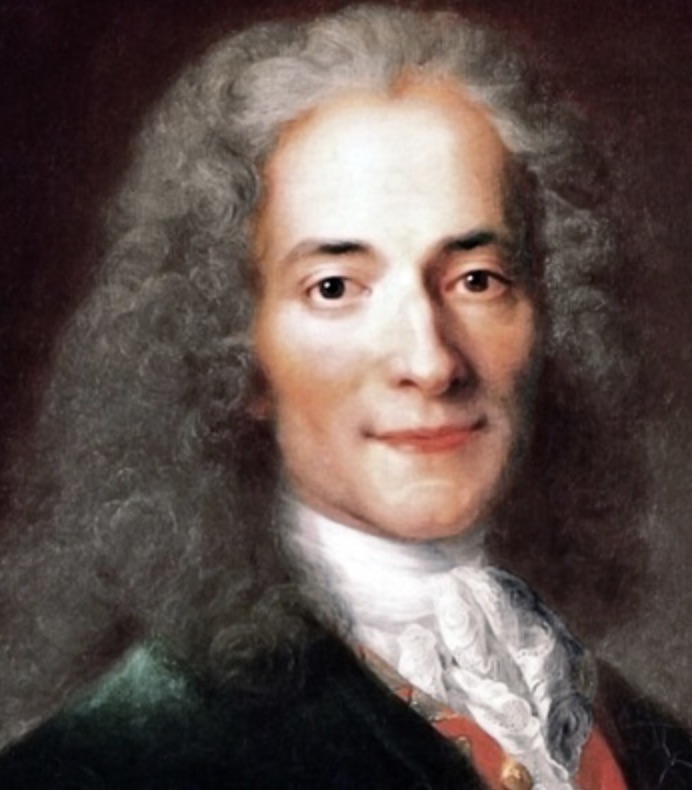

François-Marie Arouet, who later adopted the pen name Voltaire, was born on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France into a middle-class family. He received a Jesuit education at the Collège Louis-le-Grand, where he developed a passion for literature and writing. His father, François Arouet, who was a lawyer, wanted François-Marie to follow in his footsteps, and sent him to Caen where he was to study law. However, François-Marie continued to focus his time on writing poetry, and historical essays, often courting trouble with his sharp wit and criticism of the French government and the Catholic Church.

Adopting the pen name “Voltaire,” he launched his literary career in 1718 as a playwright, achieving early success with his first tragedy, “Oedipus.” This was followed in 1720 with the publication of his play Artémire that flopped, prompting Voltaire to switch to an epic poem about Henry IV of France. However, his criticisms of the French government led to the loss of his licence to publish in France, so he fled to the Netherlands with his mistress to seek a publisher. Eventually he found an illicit publisher for his epic poem that he titled La Henriade. Copies were smuggled into France and the poem became an immediate success.

In 1726, he became embroiled in a personal dispute with the aristocrat, chevalier de Rohan-Chabot. After the aristocrat sent his henchmen to beat up Voltaire, the battered playwright challenged chevalier de Rohan-Chabotand to a duel. The Rohan family used their influence to have Voltaire imprisoned in the Bastille without a trial. After almost a year of imprisonment, Voltaire asked that he be exiled to Britain as an alternative to an indefinite prison term in the Bastille.

After his release, Voltaire went into exile in England for three years, where he became immersed in English high society, hobnobbing with celebrities including Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. Voltaire’s exile in Great Britain exposed him to the ideas of the English Enlightenment and would have a profound influence on his thinking and his future writing.

Voltaire returned to France in 1729 and continued to write prolifically. He once again began to charm the French with his wit, satire, and criticism of established institutions. Voltaire was a deist, believing in a higher power, but rejecting specific religious dogmas. He was a champion of reason, religious tolerance, and freedom of thought. In 1733, he published, without permission from the French royal censor, Letters Concerning the English Nation, in which he praised the English constitutional monarchy as more tolerant of religious beliefs than its French counterpart. The book was banned in France, following public book-burning episodes, and Voltaire once again fled from Paris.

Shortly after his departure, Voltaire met a female mathematician, Émilie du Châtelet, who was married and was 12 years younger than he. They began what evolved into a long-term affair, residing at the chateau of her husband who often accompanied them. Voltaire and Émile together studied an extensive library of books on science and mathematics, including Newton’s Principia and his other works. Through his 1738 publication of Elements of the Philosophy of Newton, Voltaire brought Newton’s discoveries in optics and gravitation to the attention of the French population, supplanting Descartes’ theories in physics.

In September 1749, Émilie du Châtelet died in childbirth and Voltaire returned to Paris and then in 1750, moved to Prussia at the invitation of Frederick the Great. The Prussian king provided Voltaire with a paid position and residence in the palace. Voltaire continued to write on a wide range of subjects, including history, science, and philosophy while in Prussia. However, disputes with some of the members of the Berlin Academy of Science eventually brought a deterioration in his relationship with Frederick and Voltaire left Prussia for France. However, in January 1754, Louis XV banned Voltaire from Paris, and in 1758, Voltaire found refuge in Geneva.

It was in 1759 that Voltaire published what may have been his most famous work, the satirical novella Candide in which he criticizes the optimism of the time and explores the hardships of life. Optimism in this work is satirized in the character of the pompous Professor Pangloss who asserts, “It is demonstrable that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for all being created for an end, all is necessarily for the best end. Observe, that the nose has been formed to bear spectacles—thus we have spectacles. Legs are visibly designed for stockings —and we have stockings.” (Candide was included in Martin Seymour-Smith’s 1998 publication The 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written.)

In February 1778, Voltaire returned to Paris for the first time in over 25 years, to view the opening of his 5-act tragedy Irène. At the performance he received a hero’s welcome. It was Voltaire’s last hurrah, as he died on May 30, 1778 at the age of 83. Voltaire’s works have had a lasting impact on literature, philosophy, and the concept of human rights. His advocacy for freedom of speech and his critique of authoritarianism have made him an enduring figure in the history of ideas. His insight into those who would limit free speech is cogently captured in his statement, “If you want to know who controls you, look at who you are not allowed to criticize.”