As seen in the biographies of people like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Steve Jobs and others, children who are highly intelligent or gifted have different interests from most others and therefore cannot self-reference to understand how others feel. In their early relationships with others, they begin to realize that they don’t “fit in.” Their difference often results in their exclusion from groups. From an early age, they see themselves as “different” and the pain of exclusion makes them more desperate to become part of the group–a response that tends to alienate them even more. Sometimes, they fight back by flaunting their mental abilities or putting down others–a practice that visited grief on Bezos and Jobs.

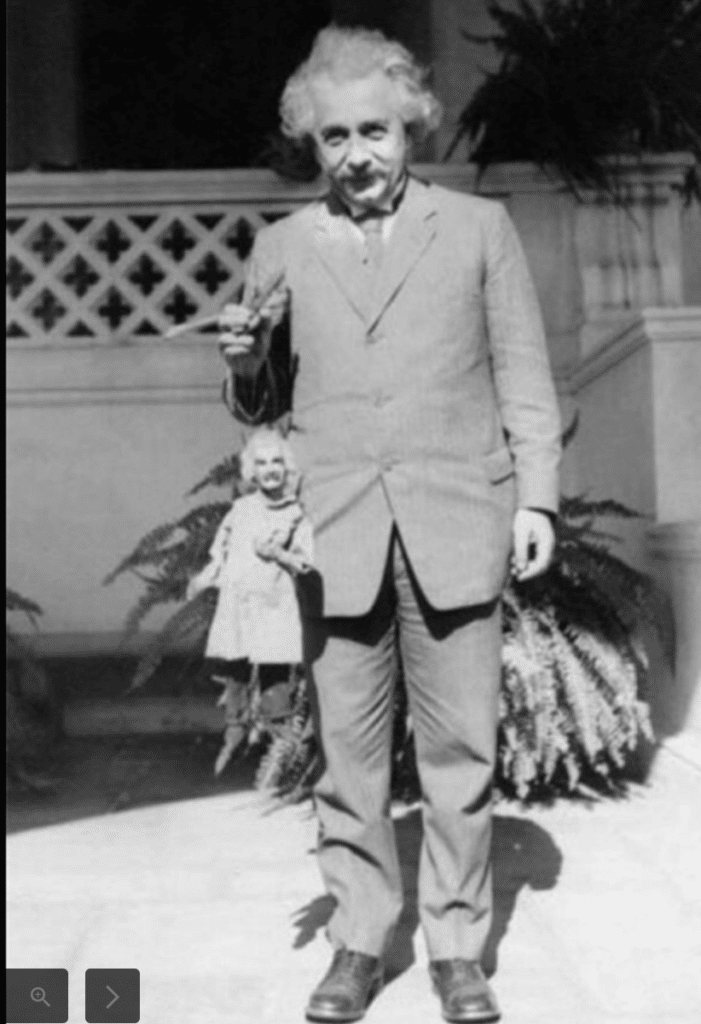

In a nutshell, perhaps the greatest problem of “smartness” or high intelligence is the feeling of isolation that comes from being different. In his final years, Albert Einstein was very lonely, and his isolation increased when one of his only friends Kurt Gödel (another gifted person) died from self-induced starvation. When asked whether he believed in immortality, Einstein responded, “No, and one lifetime is enough for me.”

The greatest weakness that threatens highly intelligent people is called the intelligence trap. (See: Does intelligence increase your ability to fool yourself? – Intelligence and IQ. Sometimes, brilliant people overestimate their intelligence relative to others and assume that their brilliance in a particular field means that they have a superiority over others in all fields, even though they lack the adequate preparation.

Quite frequently, Nobel laureates or winners of other prestigious awards, make scientifically unjustified assertions within or outside their field of expertise. This phenomenon, often described as “Nobel disease,” is a common result of confirmation bias. Indian astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who won the Nobel Prize in 1983, describes how a scientist may fall into this cognitive trap:

These people [winners of prestigious awards] imagine afterward that the fact that they succeeded so triumphantly in one area means they have a special way of looking at science that must be right. But science doesn’t permit that. Nature has shown over and over again that the kinds of truth which underlie nature transcend the most powerful minds.

The antidote to the intelligence trap is the deep humility that often accompanies high intelligence–what is sometimes referred to as “knowing what you don’t know.” As highly intelligent individuals learn more, they come to appreciate the deep complexities of the world around us and that imbues them with a sense of awe, making them slow to reach opinions, and less dogmatic in the opinions they hold. People like Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg, Stephen Hawking and others were able to achieve this balance. In essence, we are all human and subject to human frailty no matter the level of our IQ. Differing intelligence merely introduces different weighting factors on the type of frailty to which we might fall prey.