An insight into differences in human cognitive abilities was provided by psychologist Jean Piaget in the 1960’s, in his study of how children learn. His observations led him to understand that children move through three stages of understanding as they acquire a concept. He described these in a sequence from concrete, to pictorial and on to abstract.

The concrete stage: To help a child understand that 2 + 3 = 5, we have them gather 2 objects and combine them with 3 objects and then count how many objects. When they reach 5, they have a concrete perception of what is meant by 3 + 2 = 5

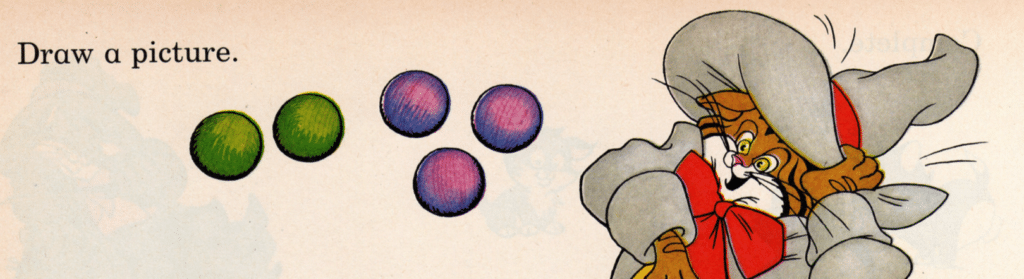

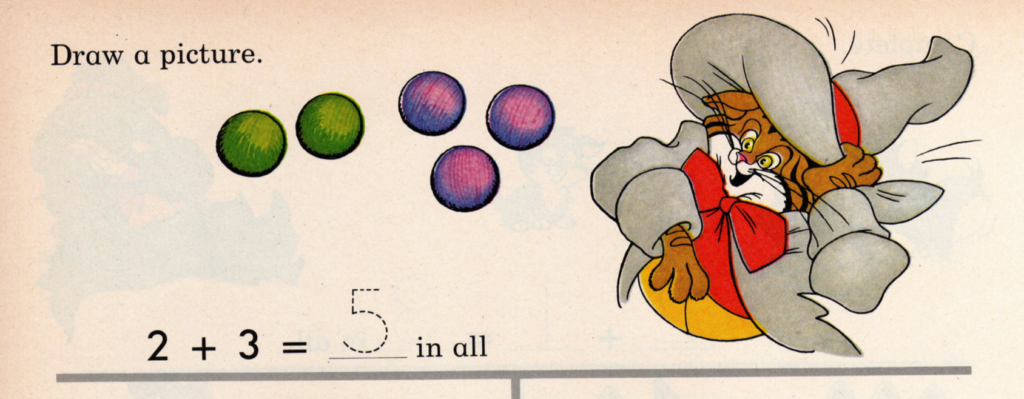

The pictorial stage: The child is given a picture like the one below and asked “How many balls altogether.” The child counts two balls and then counts on to 5.

The abstract stage: The child conceptualizes the idea that 2 + 3 = 5 independent of what items are added.

All children pass through these stages in the process of internalizing a concept. However, children move through these stages at different rates. Piaget didn’t conjecture why children differ in this regard, but recent studies in neurology suggest that people differ in brain acuity, i.e., in the speed and efficiency in which signals are transmitted across neuron paths. Even among the most brilliant mathematicians and physicists there are observable differences. Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, intimidated by the superior mathematical acuity of Yasantha Rajakarunanayake, transferred out of the mathematics program at Princeton and Bertrand Russell suffered depression over his observations of Wittgenstein’s superior intellectual prowess.

The main observable difference in intelligence among people is the capacity for abstraction. Russian psychologist Vadim Krutetskii, reporting on his extensive research on students in the former Soviet Union stated:*

The difference between capable, average, and incapable pupils, as our research permits us to conclude, comes down to the following. In able pupils these associations can be formed “on the spot”; in this sense they are “born,” if one can so express it, already generalized, with a minimal number of exercises. In average pupils these associations are established and reinforced gradually, as a result of a whole series of exercises. They form isolated, concrete associations, related only to a given problem, “on the spot.” Through single-type exercises these associations are gradually transformed into generalized associations. In incapable pupils, even the isolated, concrete associations are formed with difficulty, their generalizations are still more difficult, and sometimes such generalizations do not occur at all.

So, how are these differences manifest in people’s thinking habits? There are a large number of differences, but we’ll look at one simple example. Marsha and her two friends have lunch at a restaurant. When the bills arrive, Marsha’s friends observe that she leaves a small tip. The unintelligent friend makes a quick assumption, “Marsha is a cheapskate.” The intelligent friend asks herself, “Why did Marsha leave a small tip? Was she unhappy with the service? Are there other situations that would suggest that Marsha is stingy? Is this typical of Marsha’s general behavior?

In short, highly intelligent people look for general patterns. They gather evidence in attempting to make sense of the world and connect events to identify relationships. This makes them extremely effective in connecting causes and results–the essence of scientific investigation. The highly intelligent tend to have less interest in the typical social chit chat such as that found in a lot of social media and tend to gravitate to discussions of a conceptual nature. As Socrates is reputed to have observed over 2500 years ago, “Strong minds discuss ideas, average minds discuss events, weak minds discuss people.” For a brief look at differences in how people of different intellectual acuity form opinions, visit How are Hi-Q People Similar and Different from the Average in Reaching Opinions? – Intelligence and IQ

Krutetskii, Vadim A. 1976. The Psychology of Mathematical Abilities in Schoolchildren. Chicago: Chicago University Press. p. 262.