Throughout the development of mathematics there have been several milestones marked by their challenge to mathematical intuition. During the time of the Ancient Greek civilization around 500 BCE, it was believed that all numbers are rational, that is, they can be expressed as integers (whole numbers) or fractions of integers. Then, a group of mathematicians and philosophers called, “the Pythagoreans,” discovered that the length of a diagonal of a square with sides one unit long could not be expressed as a rational number. That is, √2 is irrational. The Pythagoreans wanted to keep this discovery a secret and the history of mathematics, contains a legend (probably apocryphal) that the Pythagorean who reveal this secret was drowned at sea for exposing this truth.

A second major challenge to mathematical intuition came in 2000 years after the development of Euclidean geometry. For centuries, mathematicians had tried, without success, to deduce Euclid’s 5th postulate (that parallel lines will not intersect) from the other four. Then, in 1824, Karl Gauss, rated by historians as one of the three greatest mathematicians of all time, discovered a geometry in which the sum of the measures of the angles in a triangle are less than 180˚ and he wrote in a letter to his colleague, Franz Taurinus:

The assumption that (in a triangle) the sum of the three angles is less than 180° leads to a curious geometry, quite different from ours, but thoroughly consistent, which I have developed to my entire satisfaction.

He called this a non-Euclidean geometry because it satisfied Euclid’s first four postulates, but violated the fifth which implies that the sum of the measures of the angles in a triangle is 180˚. If the fifth postulate could be deduced from the first four, it would have contradicted Gauss’s discovery that the first four postulates can be satisfied in a space in which the fifth is not true. In the decades that followed, Bolyai, Lobachevsky, Riemann and others developed geometries in which the fifth postulate was different from the fifth postulate in Euclidean geometry. This new geometry paved the way for the development of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in the second decade of the 20th century.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Bertrand Russell and other mathematicians were struggling to find a set of axioms from which all mathematical theorems could be deduced. Then In 1931, an Austrian mathematician, Kurt Gödel, at age 25 published his doctoral thesis, On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems. In this epoch-making paper, Gödel enunciated a theorem and corollary that registered a magnitude ten on the seismometer of mathematical quakes. The programs of both the formalists and the logicists collapsed like giant skyscrapers whose foundations had crumbled under a tectonic shift. The impact of Gödel’s discovery on the mathematics community would eventually exceed the trauma felt two millennia earlier with the discovery of irrational numbers. Though it took many years for the mathematics community at large to appreciate what Gödel had achieved, those who were working in the foundations of mathematics soon recognized the far-reaching implications of his powerful theorem and corollary. This initial shock wave eventually dissipated into a universal acceptance that absolute certainty of anything may be an illusion. An article in The New York Times in 1978 described Gödel’s Theorem as “the most significant mathematical truth of this century, incomprehensible to laymen, revolutionary for philosophers and logicians.”

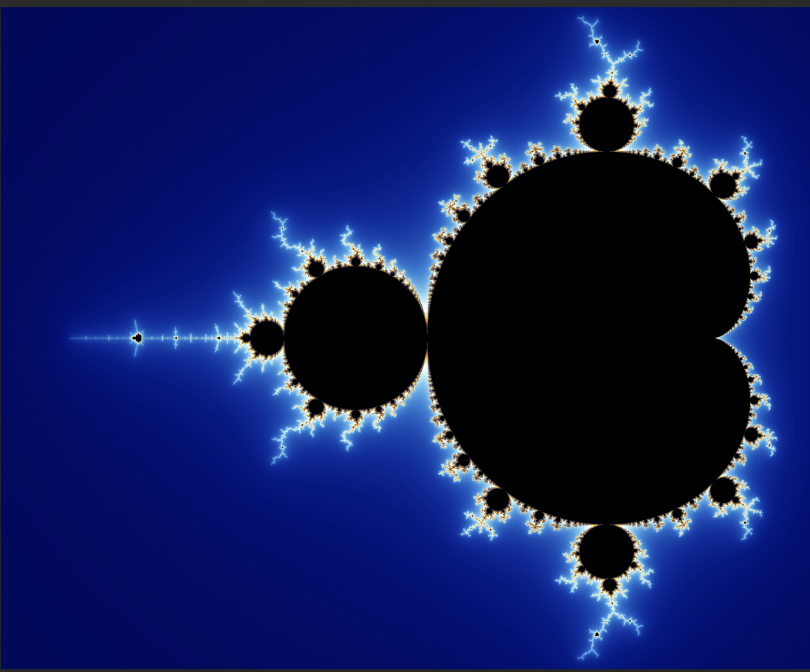

As the computer was emerging as a device for exploring mathematics, our mathematical perception of the world as a system of continuous change described by differential equations, was about to receive another shock. In 1979, maverick mathematician, Benoit Mandelbrot, while working at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center, took inspiration from an idea of Henri Poincaré, and wrote a computer program to explore the graph that results when the point 0 + 0i in the complex plane is mapped repeatedly under the transformation defined by z → z^2 + c where c is a complex number. This involves taking the point 0 + 0i in the complex plane, squaring it, adding c and then iterating this process, ad infinitum, to generate a sequence called the orbit of c. On March 1, 1980, Mandelbrot first glimpsed at the vague outline of what has become known as the Mandelbrot set, shown in the diagram above. It is the set of all complex numbers c whose orbit converges i.e., is bounded. This exceedingly complex structure that emerged from that simple iteration, ushered in what is now called the mathematics of chaos. When we “zoom in” on this figure, we discover that the boundary of the Mandelbrot set is infinitely “crinkled.” As the value of c changes imperceptibly, the orbit of c changes from a convergent to a divergent series. Mandelbrot and others showed that changing, by a minuscule amount, the initial conditions in a non-linear dynamic system can result in dramatic changes in the outcomes. This means that some systems such as weather, cannot be represented by equations that yield precisely predictable outcomes. This means that our world is much less predictable than first believed, because minor changes in initial conditions have a range of dramatically different possible outcomes.

Today, mathematics has exploded into a variety of new fields, many spawned by the development of the computer technology. Conjectures such as the Riemann hypothesis continue to be investigated through computer techniques and some of these developments might lead to more challenges to mathematical intuition. These are exciting times in these rapidly evolving worlds of investigation.