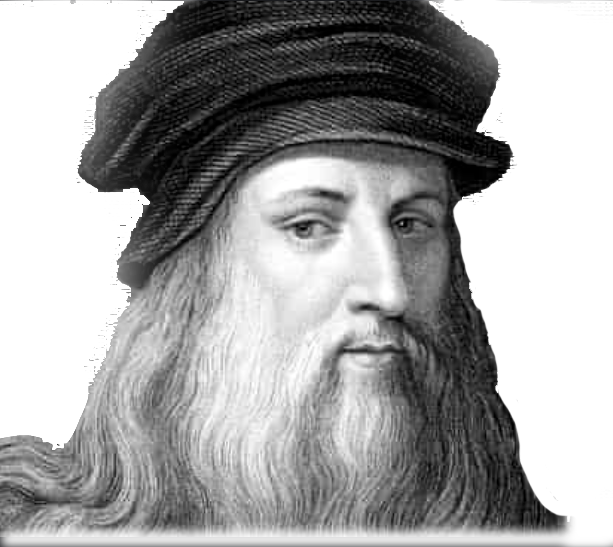

Today, April 15, is the birthday of one of the most celebrated geniuses in history–Leonardo da Vinci. Described as the “quintessential Renaissance Man,” Leonardoi–a person compelled by an insatiable curiosity to address the broadest spectrum of intellectual disciplines ever embraced by a human being–became the icon for the polymath. Born out of wedlock in the town of Vinci in Tuscany, and housed by a father who never legitimized him, Leonardo began his life free of the requirement that he become a notary like his father, Piero. This freedom, rare among first-born males, enabled him to pursue his natural interests. At age 14, the family moved to Florence and, while Leonardo had no formal schooling, he did receive informal training in Latin and mathematics–a subject with which he struggled, as he regarded the repetitive rehearsal of arithmetic algorithms and the procedures of algebra to be mind-deadening. His interest in geometry, however, was piqued by his recognition that it underpinned so much of the visual world around him. In one of his famous notebooks he recorded an insight that anticipated the development of modern science by 200 years: “No human inquiry can be a science unless it pursues its path through mathematical exposition and demonstration.”

At age 17, Leonardo began a 7-year apprenticeship to the prominent painter and sculptor Verrocchio. Under his tutelage, the young student, by age 20, had achieved status as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke. During this period, he acquired technical skills in drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and carpentry, in support of his primary focus on sketching, painting, and sculpting.

His relentless curiosity impelled his investigation of projective geometry to capture a 3-dimensional vista on a 2-dimensional canvas. He applied a meticulous study of light and its properties to his paintings so that he could imitate how light casts shadows on the folds of a cascading garment. In his painting titled “The Last Supper” he combined this knowledge with his mastery of the geometric rules of perspective to create the illusion of depth. The result was described by biographer Walter Isaacson as “the most spell-binding narrative painting in history.”7

Leonardo’s extensive dissection of cadavers to study human physiology, enabled him to display the human form in its exact proportions, as depicted in his famous sketch Vitruvian man. In Dan Brown’s best-selling novel The Da Vinci Code, protagonist Robert Langdon says:

Da Vinci was the first to show the human body is literally made of building blocks whose proportional ratios always equal PHI…Measure the distance from the tip of your head to the floor. Then divide that by the distance from your belly button to the floor. Guess what number you get…Yes PHI.”

The PHI that Langdon is referring to is the so-called golden ratio, a number that is approximately equal to 1.618 and denoted by ϕ.

Langdon’s statement implies that a person’s height is about 1.618 times the distance to their navel from the floor. Landon also asserts that the distance from the shoulder to the fingertips is about 1.618 times the distance from the elbow to the fingertips. However, whether Leonardo used the golden ratio in his construction of vitruvian man and his other paintings is still a matter of debate among scholars. (The mathematical derivation of ϕ is given in my YouTube video at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TFnMB9RkNM)

From his dissections, Leonardo da Vinci acquired a detailed knowledge of the facial muscles that express specific emotions and observed how their activation is displayed in patterns of light and shadow. This enabled him to paint the enigmatic smile of Mona Lisa that has enchanted generations of people who marvel at the magnitude of his genius.

Leonardo’s unrelenting creativity also found an outlet through technological innovation. He sketched plans for helicopters, flying machines, perpetual motion machines, and a host of other engineering artifacts–some viable and some not.

Characterizing this creative face of intelligence, Isaacson wrote:

What made Leonardo a genius, what set him apart from people who are merely extraordinarily smart, was creativity, the ability to apply imagination to intellect. …What also distinguished Leonardo’s genius was its universal nature. The world has produced other thinkers who were more profound or logical, and many who were more practical, but none who was as creative in so many different fields.

Leonardo’s genius came with its own set of anomalies. His quest for perfection was so extreme that he seldom finished a painting, always holding it in reserve with the intention of returning to add yet another stroke or two to improve it. Consequently, to the frustration of his patrons, he seldom finished a painting and rarely on time. On some days, while painting The Last Supper, he would mount the scaffold at sunrise and transition into what called the flow state, painting continuously until sunset without stopping to eat or drink. On other days, he would merely stare at the painting for an hour or two, analyze it, and depart without executing a single stroke–earning him a reputation as a procrastinator. However, Leonardo justified the behavior as a means of allowing creative ideas to incubate in his brain. Indeed, Leonardo was a creative genius whose intelligence was fed by his curiosity and nourished by the joy of free creation. According to his biographer, Walter Isaacson:

Leonardo’s genius was a human one, wrought by his own will and ambition. It did not come from being the divine recipient, like Newton or Einstein, of a mind with so much processing power that we mere mortals cannot fathom it…His genius was of the type we can understand, even take lessons from. It was based on skills we can aspire to improve in ourselves, such as curiosity and intense observation.

Profiles of others who modelled different kinds of genius are accessible at: https://www.intelligence-and-iq.com/chapter-1-the-many-faces-of-intelligence/