Since the beginning of recorded history, people have recognized that individuals differ in their ability to solve problems, deal with abstractions, and learn new ideas. We call this many-faceted ability intelligence. However, when it comes to defining this enigmatic trait, we face the famous Jainist conundrum in which three blind men grasp the tusk, trunk, and tail of an elephant and attempt to reconcile their different perceptions of this unfamiliar pachyderm.

We all have an intuitive perception of what we mean by “intelligence.” Those who see further than the rest of humanity–formulating complex theories, inventing new technologies, and making successful decisions–are seen to be highly intelligent. Those who have no interest in learning or find learning very difficult and whose lives are encumbered with a litany of self-defeating decisions, are usually perceived as unintelligent.

During more than a century of debate and discussion, cognitive psychologists have proposed a variety of definitions of intelligence and there remains a diversity of opinion. However, psychologist Linda Gottfredson advanced, in 1997, a definition that has achieved some consensus among members of the American Psychological Association (APA):

Intelligence is a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience. It is not merely book-learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather, it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings, “catching on,” “making sense” of things, or “figuring out” what to do.

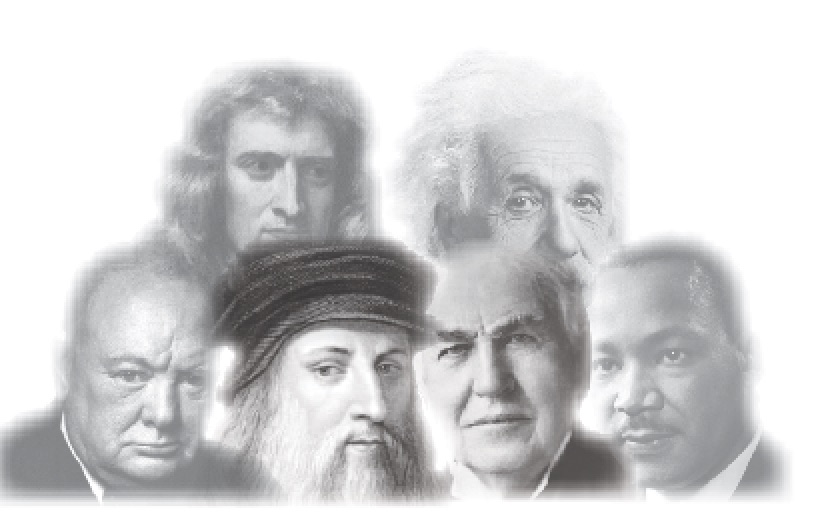

High intelligence plays out in a variety of ways. In oratory it was evident in the speeches of Sir Winston Churchill and Dr. Martin Luther King. Albert Einstein and Grigory Perelman expressed their high intelligence through their capacity for abstract thought, while Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos demonstrate their high intelligence as entrepreneurial insight. Intelligence has many faces that are most vividly evident when compared with the capabilities of the average. That is why IQ, our best, albeit somewhat limited measure of intelligence, is expressed in percentiles.

To what extent is intelligence determined by genetics, and to what extent is it inheritable? In 2011, a large group of researchers published the results of a genome-wide analysis of 549,692 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) involving 3511 unrelated adults. (An SNP represents a difference in a single DNA building block, called a nucleotide.) (See: Davies, G., A. Tenesa, A. Payton, J. Yang, S.E. Harris, D. Liewald, et al. 2011. “Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic.” Molecular Psychiatry. 16. pp. 996–1005.) They reported:

Our results unequivocally confirm that a substantial proportion of individual differences in human intelligence is due to genetic variation, and are consistent with many genes of small effects underlying the additive genetic influences on intelligence. … [Furthermore] purely genetic (SNP) information can be used to predict intelligence.

This research estimated the heritability of IQ to be about 0.5, confirming the results of the studies involving twins. Its conclusion that general intelligence is polygenic, i.e., it derives from a combination of many genes supports the concept of intelligence as a multi-faceted characteristic. In his 2016 book, The Gene: An Intimate History,Siddhartha Mukherjee wrote:

While some combination of genes and environments can strongly influence g, this combination will rarely be passed, intact, from parents to their children. Mendel’s laws virtually guarantee that the particular permutation of genes will scatter apart in every generation. … . Intelligence, in short, is heritable (i.e., influenced by genes), but not easily inheritable (i.e., moved down intact from one generation to the next).

Mukherjee is arguing that since g is polygenic, and is derived from a random selection from two parents, a specific combination of genes in either parent has a low probability of passing intact to the offspring. However, if both your parents have a high intelligence, you have a better chance of having high intelligence than someone whose parents are of average intelligence–partly attributable to genes, but also attributable to your home environment in your formative years.

Part of the response to this question was excerpted from the book Intelligence, IQ & Perception. For more detailed information on the inheritablity of intelligence, see my earlier post at: How hereditary is IQ? My mom has an IQ of 140 and my dad 136. Is it possible that I would score a similar score? – Intelligence and IQ