Since the beginning of recorded history, people have recognized that individuals differ in their ability to solve problems, deal with abstractions, and learn new ideas. We call this many-faceted ability intelligence. However, when it comes to defining this enigmatic trait, we face the famous Jainist conundrum in which three blind men grasp the tusk, trunk, and tail of an elephant and attempt to reconcile their different perceptions of this unfamiliar pachyderm.

We all have an intuitive perception of what we mean by “intelligence.” Those who see further than the rest of humanity–formulating complex theories, inventing new technologies, and making successful decisions–are seen to be highly intelligent. Those who have no interest in learning or find learning very difficult and whose lives are encumbered with a litany of self-defeating decisions, are usually perceived as unintelligent.

During more than a century of debate and discussion, cognitive psychologists have proposed a variety of definitions of intelligence and there remains a diversity of opinion. However, psychologist Linda Gottfredson advanced, in 1997, a definition that has achieved some consensus among members of the American Psychological Association (APA):*

Intelligence is a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience. It is not merely book-learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather, it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings, “catching on,” “making sense” of things, or “figuring out” what to do.

A significant difficulty in defining intelligence with some level of precision derives from the fact that intelligence is manifest in a variety of different ways–sometimes in creativity, sometimes in oratory and sometimes in a deeply abstract conceptualization of ideas. You can visit some human personalities exuding each facet at: https://www.intelligence-and-iq.com/the-many-faces-of-intelligence/.

In 1904, English psychologist Charles Spearman tested 23 boys in a preparatory school near Oxford on each of: classics, French, English, mathematics, discrimination of pitch, and music. He discovered that someone who scored high on one test, tended to score high on all the others. On analyzing these correspondences, that psychologists call “correlations,” he asked, “What pervasive cognitive faculty accounts for the fact that a student who does well on any of these tests, usually, but not always, does well on the others?” Spearman hypothesized that the cognitive abilities brought to bear in each test consist of a general ability, common to all the tests, along with a specific ability unique to that test. He called this general factor of cognitive ability the g factor which he computed from the table of correlations, using a mathematical technique known as factor analysis. This g factor became a measure of an individual’s component of intelligence that pervades all cognitive processes. We might think of this as cognitive efficiency, or the ease with which a person’s brain absorbs, processes and organizes information.

Today, our best measure of intelligence is the IQ test, not those offered on line, but professionally administered tests such as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale and the Wechsler scales. These tests measure dimensions of intelligence that have a strong correlation to performance on SATs (student achievement tests often administered for college admissions.) These tests are scaled so that the average IQ of a population registers as 100 with a typical standard deviation of 15 or 16, so that each IQ score expresses the percentage of people who scored below it.

While an IQ test is useful as a first approximation of an individual’s intelligence, it does not measure inventiveness, creativity, or deep problem-solving ability, Consequently, IQ’s above 140 are difficult to interpret and it is difficult to rank people above this level. For example, some mathematicians are brilliant at long-term problem solving but are merely superior at timed tests–similar to the difference between speed chess and chess. The highest levels of intelligence and creativity that we often refer to as “genius” is not measurable except through achievement. Borrowing from a comment of Justice Potter Stewart of the US Supreme Court, “Intelligence is like porn, difficult to define, but you know it when you see it.” The same may be said of genius. When Isaac Newton submitted anonymously his solution to the brachistochrone problem posed by the great mathematician, Johann Bernoulli, the latter announced, “I recognize the lion by his paw.”

• Gottfredson, Linda R. “Mainstream Science on Intelligence: An Editorial with 52 Signatories, History, and Bibliography,” Intelligence 24 (1997): 13–23. The quote is on page 13.

Nothing is measurable. It is a false premise of abstract reality. You need dualism, aka a base point of reference. Sorry but the universe does not provide a true point of reality.

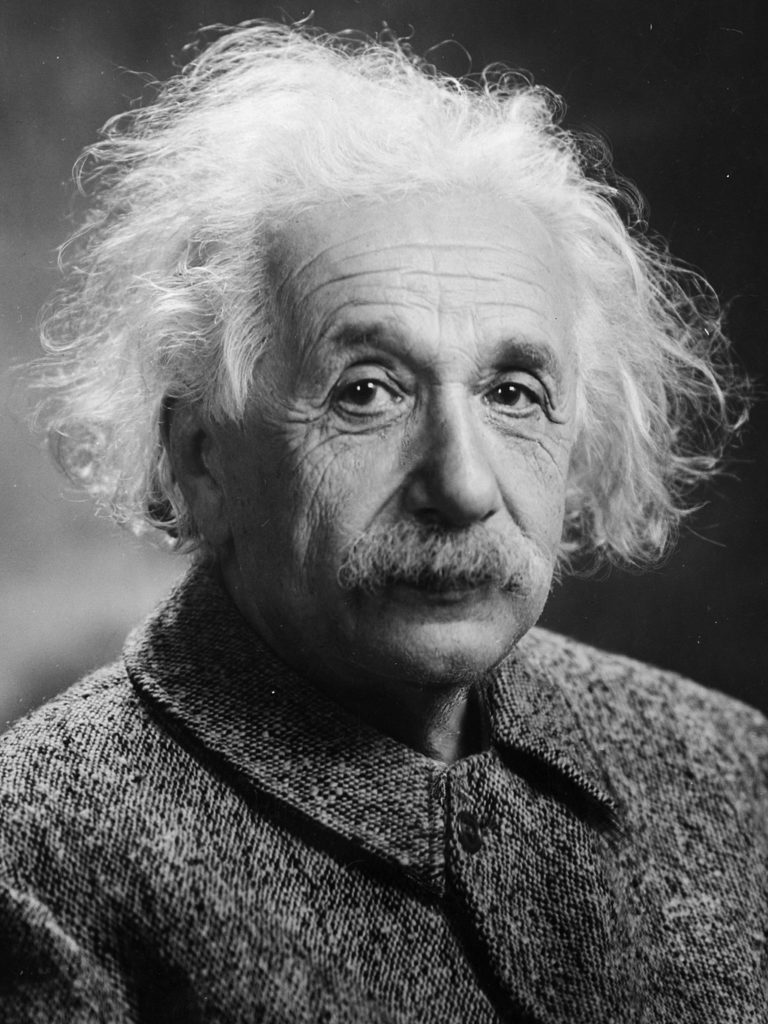

Take Einstein, he was fortunate or unfortunate to have a blood magnetic aneurysm in his brain, which give him a higher tau zero coupling cell overall binding especially looking at the sun all day in his bay window at Princeton. Electric hair just waiting for lightening to strike.

With great intelligence comes great mistakes.

Thank you for your comments, Gump.