We have all met people who speak with great certainty about things in which they are not well versed. When challenged they tend to double down on their certainty and refuse to accept the possibility that they may be mistaken.

I had a brother-in-law, now deceased, who used to respond to any of my opinions with the assertion, “No that’s wrong! Do you want to know the thing of it?” To this question I would respond, “O.K., tell me what you think.” He would then give a long explanation of “the thing of it” revealing that he knew very little about the subject and was confused. However, he was not open to suggestion, so it would be a waste of time, and perhaps unkind, to point out the flaws in his argument. My typical response was, “You could be right, Sam, I’ll have to do a little more research.” Then, I would change the subject and ask him what was going on in his life.

Sam’s problem was that he had been a poor student and dropped out of high school after completing Grade 9, and he felt he had to prove to everyone that he was intelligent in spite of his lack of a high school diploma. Admitting he was wrong on an issue would be (in his eyes) an admission of intellectual inferiority. His behavior was self-defeating because, if he were open to rational discussion and expressed interesting insights, I would have thought he was a highly intelligent person who merely dropped out of school.

People who will not admit that they could be wrong are usually terrified that people will discover them lacking in information and perhaps not authoritative in some area. Even some people with a lot of formal education suffer from this need to be an authority on all things. Shakespeare mocked such behavior in his play, The Merchant of Venice when Gratiano asserts, “I am sir Oracle, and when I ope my lips [to speak], let no dog bark …”

The truly intelligent man or woman is eager to learn and is highly receptive to the ideas and opinions of others. We learn far more from those who have a different opinion than from those who agree with us. But it takes an emotionally secure and confident person to acknowledge an error or a limitation, and this humility is ingratiating to others who sense a depth of inner strength.

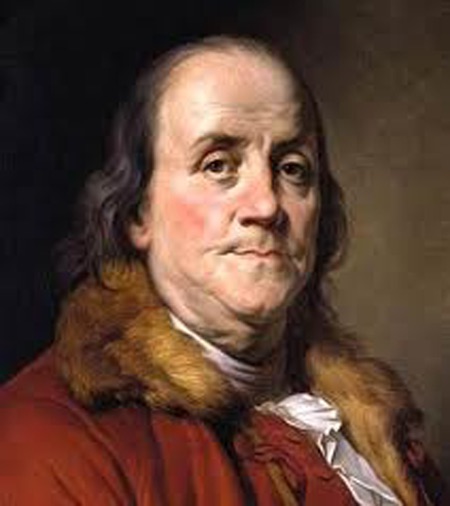

Ben Franklin may be an icon for this behavior. His speech at the Continental Convention, in its power to move the delegates from discord to harmony, displayed his wisdom and understanding of human nature. He knew the persuasiveness of confessing fallibility to encourage others to acknowledge the limits of their own perceptions. As expressed in an aphorism he had written in Poor Richard’s Almanack 4 decades earlier,“ None but the well-bred man knows how to confess a fault or acknowledge himself in an error.”

Employing both true humility or perhaps, its pretense, he was able to disarm those of opposing opinions. Staying relatively quiet and rational, while others were consumed with passion, was a technique he had developed that enabled him to negotiate agreement where no accord seemed possible. This rational habit of mind could be a chapter in a treatise on emotional intelligence.