When I was an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, enrolled in a special course titled, “Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry,” we had some outstanding professors who were also showmen, in the style of Richard Feynman. Every Christmas they would put on a demonstration called “A Christmas Box Lecture.” It was an annual ritual on the last day of the fall term that drew an overflowing audience from the Faculty of Engineering, the Physics Department, the Mathematics Department and anyone who wanted some pre-holiday entertainment.

The presentation was delivered in a large lecture hall in the old McLennan Lab building close to the site where insulin had been discovered by Drs. Banting and Best forty years earlier. As I entered the tiered lecture hall from the back door, I could see that I was already too late for a seat, but tall enough for standing-room observation. The desk at the front of the room, a story-and-a-half below me, resembled the laboratory of the sorcerer’s apprentice. There was a profusion of flasks, connecting tubes, Bunsen burners and steaming potions. The sorcerer himself, was Professor Hallett, a comedian by nature who enjoyed filling the blackboards with equations and then lowering the auxiliary blackboard by leaping into the air, grasping the handle above his head and riding it to ground level.

On this festive day, Professor Hallett did not disappoint. Adorned in the white smock of a mad scientist, he peered up at us through thick glasses, that reflected the overhead lights in occasional flashes. In his Oxfordian accent he held forth, “Today, we are going to visit the mogic [magic] of science. Note taking will not be nessessry [necessary], but carefo [careful] observation will be rother [rather] important.” Then he ignited a beaker of liquid with the bunsen burner and, as the flames leapt ferociously upward, he brought the beaker to his lips and drank the contents. Gasps heard throughout the audience punctuated the silence that preceded a thunderous applause. “It’s ’owol [all] about the powu [power] o’ the mind,” he asserted with great aplomb, placing a forefinger on his temple.

Then the performing professor was handed a pair of oven mitts by his robotic associate. He ceremoniously inserted his hands like a prize-fighter donning his gloves for battle. Leaving the flaming burner, he approached a beaker from which a thick white vapor was escaping in billows that resembled smoke rising from an industrial stack on a cold winter day. “Liquid nitrogen at seventy degrees Kelvin,” he asserted, as he reached with tongs into a bowl containing two goldfish. He extracted one of the goldfish with the tongs and inserted it into the liquid nitrogen. There was a brief sizzling sound and then he extracted the fish. “Hod [hard] as a rock, you can see,” he said, as he knocked the frozen fish on the desk. “Dead as a doornail!” Then he smashed the frozen carcass on the desk, sending splinters of frozen goldfish across the flat surface and onto the floor. The audience gasped in horror at witnessing the instant taking of a life.

Ever the performer, Professor Hallett relished the audience reaction to his theatrics. “ ‘Tis what we call in physics, an irreversible process!” Then, taking the demonstration to the next level, he grasped the tongs and extracted the second goldfish. His apprehensive audience watched with a mixture of curiosity and dread. The animated professor inserted the tongs once more into the liquid nitrogen that boiled up to meet its prey. Within seconds, he extracted the fish, tapped it on the desk and announced, “Dead as a doornail!” There was an expectant hush as we waited for his next trick.

“Would you like anotha [another] smashing success?” he asked. The audience indicated by their response that once was enough. “Cheerio, I’ll just retire him to the bowl.”

As the solid goldfish sank slowly to the bottom of the bowl, Professor Hallett ceremoniously removed his gloves. The prize fight was over and the opponent was vanquished. A minute or two later, there was a buzz in the audience that grew quickly into a voluble hum of disbelief. The “dead-as-a-doornail” goldfish began to flicker and move. Then, as if it were shaking off a bad fall, it shimmered and swam around in the tank. The Professor, looked up at the audience in the amphitheater and gave the kind of mischievous grin that says, “I know something you don’t.” There was a resounding applause. The ebullient professor accepted the acclaim with the grace of a maestro on a third curtain call.

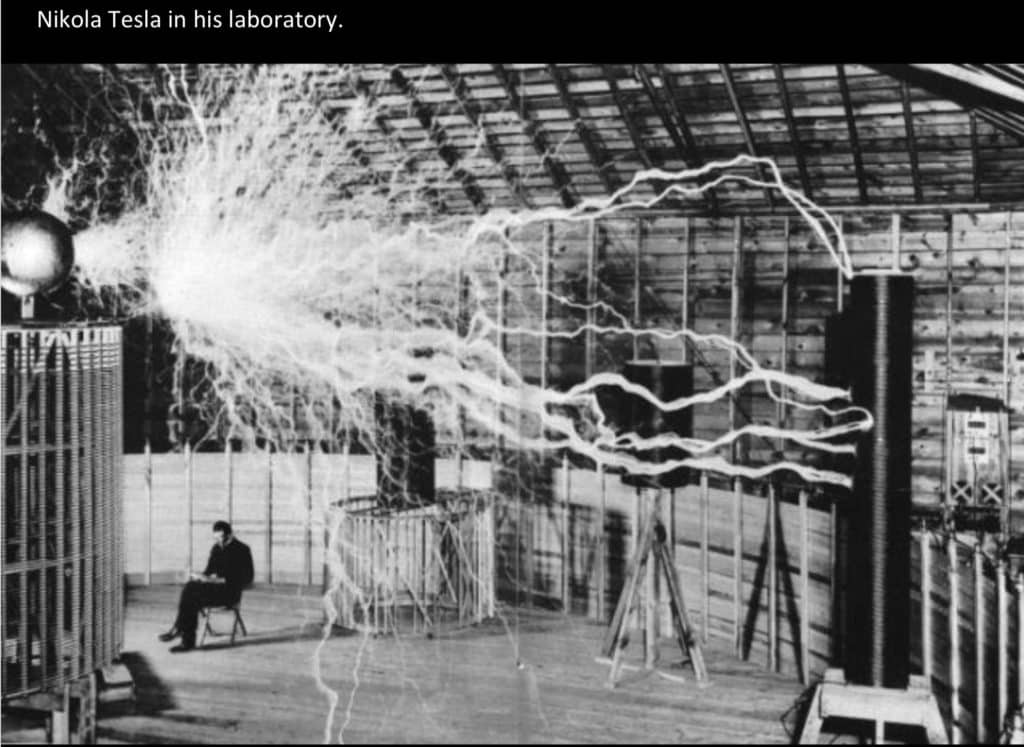

During the next hour, Professor Hallett, with the assistance of his colleague, continued to dazzle us and challenge our confidence in our perceptions. As a grand finale, he rolled in a large electrical device announcing, “And now for a hair-raising experience.” Professor Hallett invited a student to shake his hand. One rowdy miscreant, who must have come from the Faculty of Engineering, was goaded by his friends to accept the invitation. When he grasped the hand of the professor, the student’s hair stood on end, as if he’d seen a ghost. The audience exploded. Then, after a pregnant pause, Professor Hallett walked over to a Bunsen burner and placed one hand on the generator and the other hand over the burner, announcing, “ ‘proximately 20,000 volts!” A blue flame burst forth engulfing his finger, and igniting the burner. He quickly removed his finger as the thundering applause continued. Then he raised his arm to expose a large metal spike that he was holding in his hand. “I employ the spike so as not to burn my finger,” he announced triumphantly. Professor Hallett was human after all.

Our standing ovation paid tribute to the two professors who so graciously planned and delivered an entertaining lecture designed to pique our shared fascination with the marvels of science. Some of the tricks we saw were easy to explain, but others left us asking questions. Most of all, we learned to mistrust our perceptions, to check our assumptions, and to always be on the lookout for what we would later recognize as unknown unknowns.