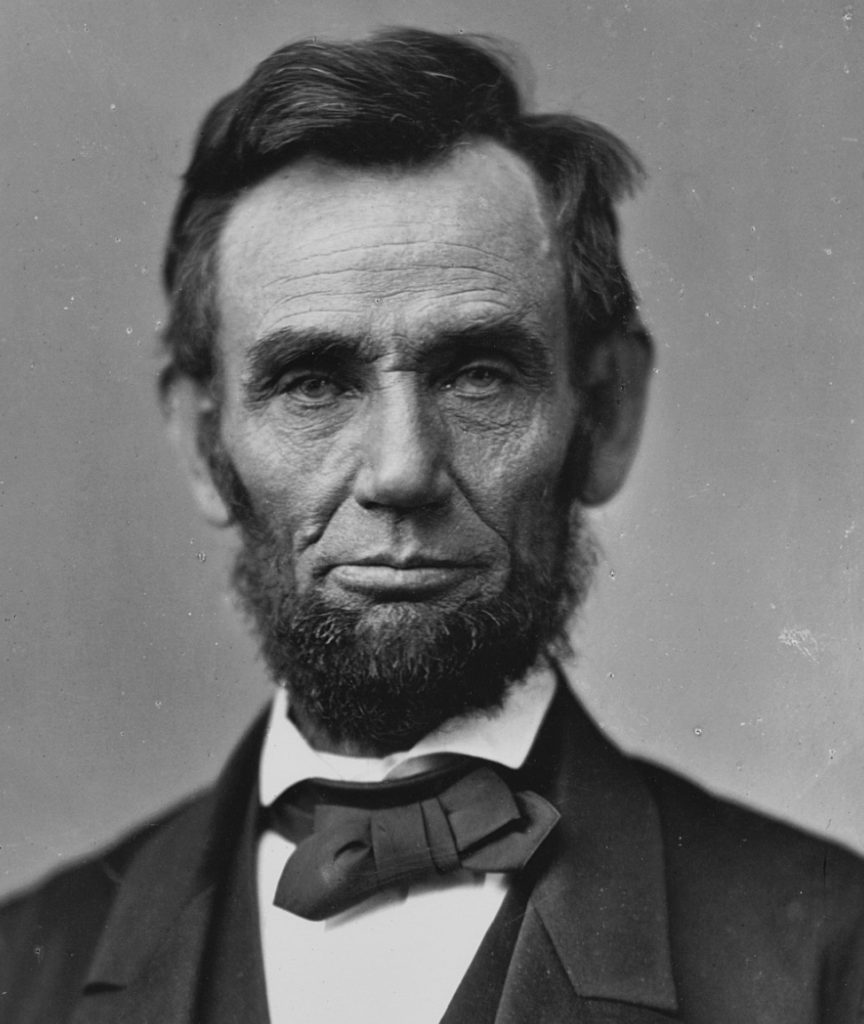

Today, we celebrate Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. Inaugurated as the 16th President of the United States in 1861, when America was on the brink of civil war, he was facing the greatest challenge to the nation’s survival since the American Revolution. The appeal of his speeches during his candidacy that won him the election would become one of his greatest assets in rallying the Union army during its darkest moments. Perhaps the most famous of his oratories was his 272-word speech, delivered on November 19, 1863 to an audience of 15,000 in Gettysburg, PA where 23,000 Union troops had perished the previous July. Though delivered in less than two minutes, his spell-binding words captured the underlying purpose of the war and of the nation, while also paying tribute to those who made the ultimate sacrifice in its cause. His speech began:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that “all men are created equal.” Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might live.

and concluded with:

It is rather for us, the living, to stand here, we here be dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that, from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here, gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people by the people for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

“Honest Abe,” as he was affectionately known, had not learned to read until age 7 and was mostly self-schooled, and yet he developed oratory skills with the power to motivate a people in a common cause. Was his oratory genius an in-born skill or was it acquired?

In their book, Abraham Lincoln and the Structure of Reason, authors David Hirsch and Dan Van Haften argue that Lincoln structured his speeches along the lines of Euclidean proof, believing that any persuasive argument, should follow the structure of a Eucliean proof by laying out the proposition and developing the ideas in a logical sequence that leads to a conclusion. The authors state:

After having laid down his major premise, he would then follow it up with his minor premises with such clearness of statement, closeness of reasoning, marshalling all the evidence, all the facts, as a great military commander does his troops upon the one given point of attack, all to prove, to the point of probability or to the point of moral certainty, the truth or wisdom of the proposition in question.

While Lincoln was highly disciplined in his writing, he also had the high intelligence that enabled him to provide witty responses to impromptu questions. Thomas Lowry in his Personal Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln recounted one storyin which Lincoln demonstrated his quick wit.

One day Lincoln, Stephen Douglas, and Lovejoy were traveling together in a stagecoach to Bloomington, Illinois for a court case. Douglas, with his long torso and short legs, looked over at Lovejoy and poked fun at his short body and disproportionately long legs. Lovejoy returned the jab by mocking Douglas’s long torso and short legs. In the midst of this good-natured ribbing, one of them turned to Lincoln and asked, “How long should a man’s legs be in proportion to his body?” Lincoln, in his typical wry fashion, replied, “I have not given the matter much consideration, but on first blush I should judge they ought to be long enough to reach from his body to the ground.”