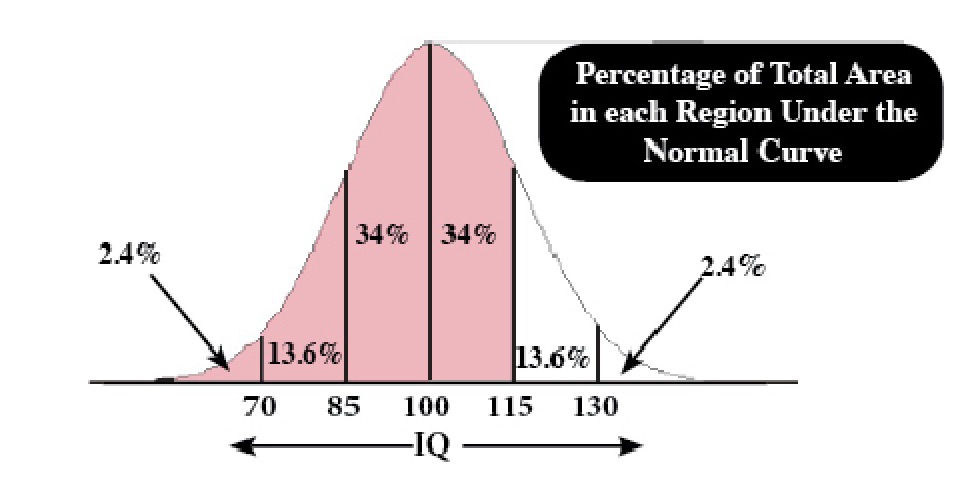

The world is designed for people who are considered “normal” in height, weight, intelligence, and other mental and physical characteristics. Airplanes and theaters have seat sizes that punish those who are much taller than average. Airplane overhead racks punish those who are shorter than average. Radio and television programs are designed for people of average interests and tastes in music, art and athletics, because most people orbit close to the center that we call “normal” or “average.” Television and radio commercials are aimed at the average, because that’s the largest market. So, if you are within a standard deviation (15 IQ points) of the average, you will be able to relate to more people and you will probably find that radio and television programs as well as movies are more tailored your interests than to the interests of the low-intelligence or high-intelligence person. In short, there are advantages to being average or “normal.”

During our school years, we are developing our social skills and evaluating our self-concept based upon how we are perceived by our fellow students. There is a strong need to be accepted by our peers and to “fit in.” People of very high intelligence tend to be interested in different things from those who are closer to “normal.” Consequently, they tend to have more difficulty understanding others and being understood by others. These social difficulties impel some to seek out others of high intelligence, as modeled in the long-running sitcom The Big Bang Theory. Others attempt to find acceptance or “fit in” with the “cool” social groups by suppressing their difference and “dumbing down.”

By the time we graduate from high school, we have learned that bragging about our achievements or ostentatiously displaying our financial status may bring us a level of respect, but it will come with a strong dose of vitriol from those who are made to feel inferior. We learn that humility or its pretence tends to increase our likability coefficient. As Ben Franklin advised in Poor Richard’s Almanack, “None but the well-bred man knows how to confess a fault or acknowledge himself in an error.” Self-deprecation is, indeed, an endearing quality. That is why intelligent people will often appear self-denigrating.

However, this brings us to a moral quandary. If a highly intelligent person presents themself as less intelligent than they are, in order to gain acceptance, can they be accused of disingenuous behavior? In order to turn an intellectual gift into achievements, a person must have strong self-efficacy bordering on arrogance. Einstein was extremely gracious in his praise of others, yet he had to believe in his intellectual gifts to propose and promote a theory that challenged firmly-held beliefs of the scientific community. The “takeaway” message would seem to be that if a highly-intelligent person wishes to be socially accepted, they must tone down any self-promotion without rejecting their belief in their own gifts. A difference between our private and our public personas might be dictated by human nature.